Babies are cared for every day under Dr. Tiem Shamy’s watch in the Children’s Hospital of Aleppo, a city that has become the focus of fierce fighting in Syria and where hundreds of thousands of civilians have been deprived of water, food and electricity.

The delivery of medical supplies requires passage through a treacherous narrow corridor leading to the Turkish frontier, meaning Dr. Shamy, one of two pediatricians in the besieged city where 120,000 children still live, often does not have the provisions needed for post-natal care. It is not always possible to consult more traditional medical references, so Dr. Shamy says he turns to mobile applications that help health-care professionals around the world share cases.

One such digital platform, Figure 1, was created by a Canadian startup. Users upload cases to the app – usually a picture taken on their smartphone with a short caption – and typically get feedback in 30 minutes from a health-care professional somewhere in the world. A privacy tool ensures cases are safe to share and images are reviewed by moderators to ensure any information regarding identity or location is stripped before they are posted. Users can also request insight from a particular specialist to speed up the process.

Apps such as Figure 1 have proven to be indispensable for physicians treating patients at the forefront of the Syrian civil war, where medicine and other shortages are commonplace, according to medics inside Syria and also Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, where millions of refugees have fled. In eastern Aleppo, where only 15 to 20 doctors remain to treat 300,000 citizens, limited resources complicate the extent to which physicians can treat patients. This is where telemedicine has proven to be a valuable tool, said Dr. Shamy.

“[Figure 1] has helped with diagnosis. It also enables us to consult a wide range of specialists and experienced physicians,” Dr. Shamy said in an interview, taking a break between shifts in the hospital, which is located in the rebel-held eastern district of Aleppo. The area has faced an unprecedented barrage of airstrikes after a ceasefire agreement collapsed last month. The Syrian government’s air campaign, reinforced by a ground offensive, has badly damaged hospitals in the area, and has put two out of service, medics said.

On one occasion where consulting colleagues was not possible, Dr. Shamy, who also uses similar apps such as Nelson and UpToDate, checked Figure 1 to calculate the correct dosage of vancomycin, a bacterial antibiotic, for a premature newborn. And when another infant exhibited signs of tramadol poisoning after being given too much of the pain reliever by a nurse, he scrolled through similar cases on the app to find the right treatment.

Dr. Shamy works with the Independent Doctors Association, a Syrian medical NGO based in Gaziantep, in southern Turkey, that co-ordinates and supports facilities in Aleppo province.

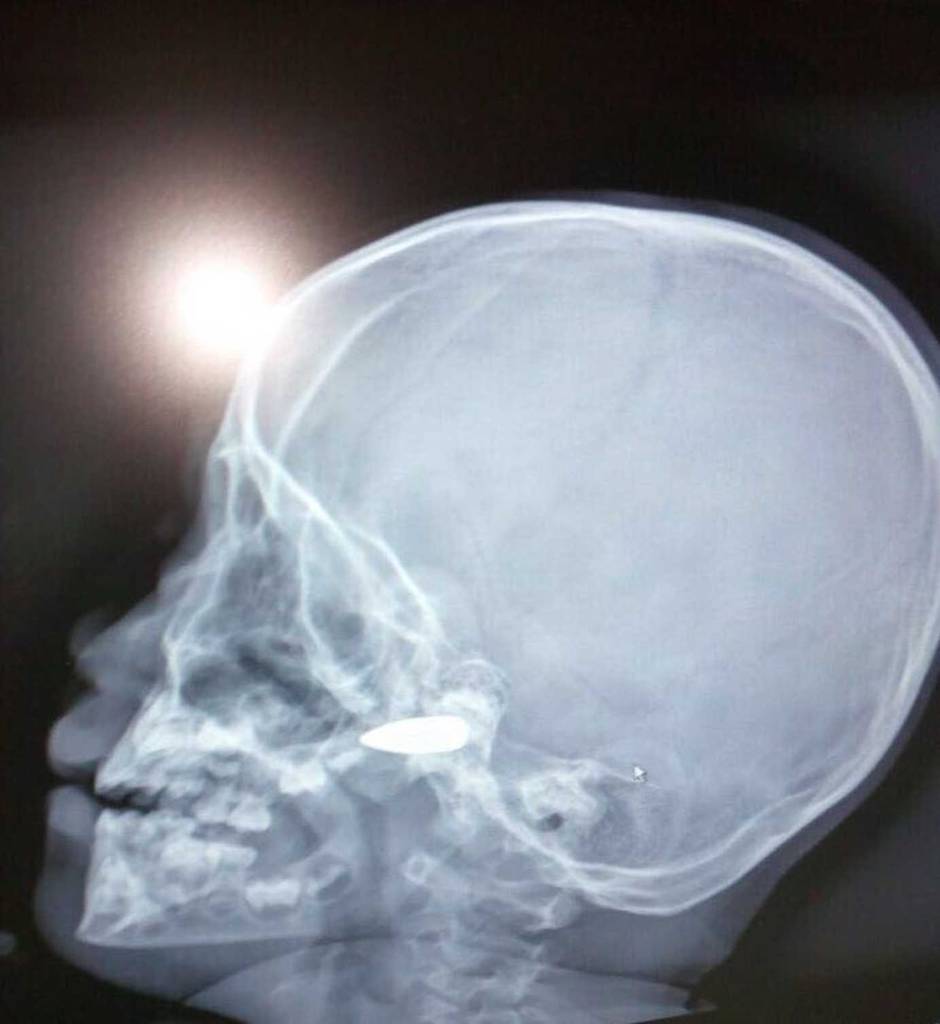

Posts from physicians working in neighbouring countries that have been overwhelmed by spillover from the Syrian civil war have flooded the Figure 1 app. One doctor requested assistance with the case of a three-year-old Syrian refugee girl with sagging skin; she “lives in a tent on the Syrian border with absolutely NO resources so forget genetic testing,” read the post. Another asked for help to diagnose a nine-year-old recently arrived from Syria with a unilateral congenital skin lesion. A doctor in Israel posted a photo of a Syrian rebel who had come into the country for treatment with shrapnel wounds so severe his face was not identifiable.

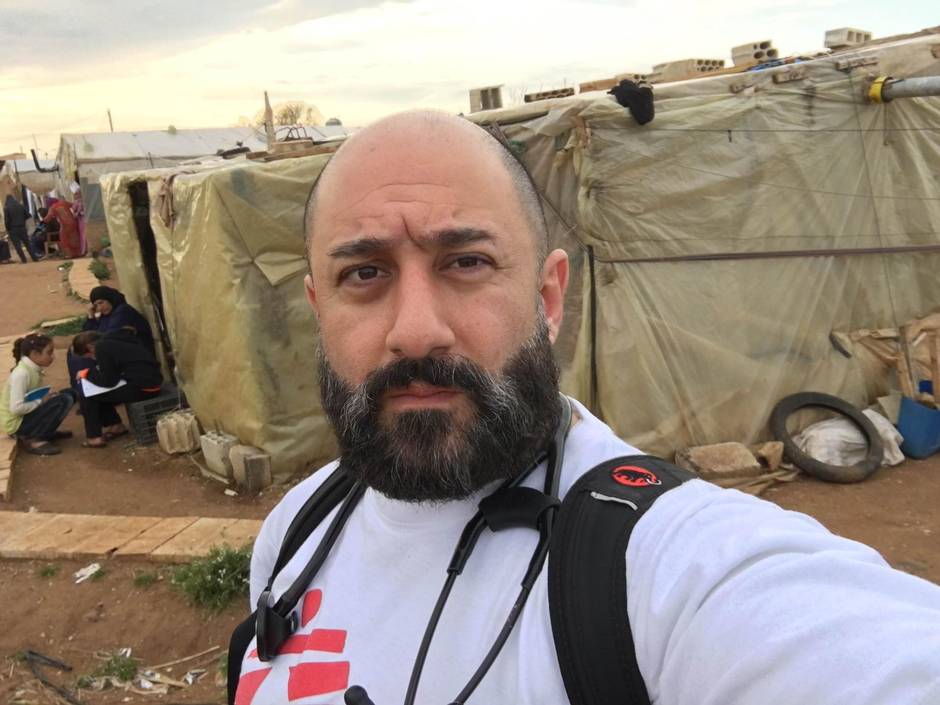

In rural Lebanon, where access to specialists is costly and patient files sometimes consist of sticky notes and folders, Figure 1 is often used to provide medical support, explained Canadian emergency physician Rogy Masri, who worked with Médecins sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in Tripoli, Lebanon, from December, 2015, to June of this year.

In one instance, Dr. Masri treated a middle-aged Syrian patient who approached the clinic with a bulbous ulcer on his right hand. “I’d never seen it in North America,” the doctor recalled.

When consultations with Lebanese colleagues did not lead him any closer to a definitive diagnosis, he uploaded a post to Figure 1. Within minutes, Dr. Masri had an answer: “Differential diagnosis: cutaneous #Leishmaniasis, #Mycobacterial-infection or #Squamous-cell-carcinoma. A biopsy should be done to definitively exclude cancer and it should be cultured,” replied “User A,” identified as an internal medicine resident.

“User B” jumped in: “Don’t forget the great pretender – #Syphilis.”

“Will treat as #Leishmaniasis and see how he does,” Dr. Masri responded.

Dr. Masri had read about the parasitic skin disease, which is endemic in Syria. With the influx of more than 1.1 million registered Syrian refugees to Lebanon, it has become more prevalent in that country, even prompting the Lebanese Health Ministry to sound the alarm of a possible epidemic.

Three years since it was launched in Toronto, Figure 1 boasts more than one million users in 190 countries, working well beyond the scope that co-founder Josh Landy, a critical-care specialist, originally had in mind for the tool.

“I am not sure I even recognized the type of power this kind of technology could have,” he explained. When the team started building the app, it was meant to be a medical education tool for physicians who, according to a study authored by Dr. Landy when he was a visiting scholar at Stanford University in 2012, showed a propensity to collaborate with colleagues on cases via text and e-mail using mobile devices. “I didn’t foresee it could branch out into clinical practice.”

A doctor in the Solomon Islands, for instance, uploaded a case of a patient complaining of chest pains. “He was the only doctor in the area and he was working with broken machines and expired medication,” Dr. Landy said. In a village sequestered in the Peruvian rainforest where accessing a hospital requires three flights, a local doctor uses the app to gauge whether patients absolutely need surgery and ought to make the long trip.

Dr. Masri heard about Figure 1 while training to be a doctor in Canada. He ventured to Lebanon on Dec. 13 of last year, inspired still by a talk he had heard years ago, while an undergraduate, by former MSF president James Orbinski on the rising need for humanitarian intervention around the world.

Before he left for Lebanon, he worked in the emergency rooms of several Ontario hospitals including North Bay, Sunnybrook and Stevenson Memorial. In Lebanon, he is a non-communicable disease specialist for MSF’s Tripoli project, but also co-ordinates with other clinics in the Bekaa Valley.

But his training in North America could not have prepared him for the trials of working amid a refugee crisis in rural Lebanon. “Trying to identify what is realistic when the best possible care is not always possible here is challenging,” he said.

The needs, five years into the Syrian crisis, are still rising. Last year, MSF provided 200,000 consultations in Lebanon; most were for children under the age of five. Almost 50,000 were for patients with chronic diseases who require medication regularly but can rarely afford it.

According to Paul Yon, MSF’s head of mission in Lebanon, the challenges of providing free medical care in a health system that is largely privatized are manifold. “By opening various clinics across Lebanon – primary health-care clinics, non-communicable diseases clinics, maternities – MSF finds itself in the tricky situation … competing with private paid health structures.”

For capacity and financial reasons, Mr. Yon said, MSF is not able to refer all patients to specialists. “For certain illnesses, cancer, for example, we arrive to the limits of our capacities.”

Dr. Masri sees between 50 and 80 patients daily and might work 12-hour days. By 7 a.m., refugees line up outside the clinic.

He began using Figure 1 because it was convenient. In Lebanon, unless a memorandum of understanding is in place for a patient to avoid fees, it is challenging to find a specialist to whom to refer patients. In these cases, Dr. Masri will upload the case to the app and, somewhere in the world, a health-care professional will respond free of charge.

“Sometimes patients need tests they can’t afford, so we have to do the best we can with what we have,” he said.