Ask the average person to name five famous artists, and almost no one will name a woman. Those who can, though, will almost certainly name Georgia O'Keeffe.

The American modernist painter's ambiguously

eroticized depictions of calla lilies, irises, petunias and poppies have captivated the popular imagination for decades – despite her steadfast, lifelong denial that they were anything other than close-ups of flowers.

As David Hockney's paintings of

Los Angeles look more like our idea of the city than the place itself, New Mexico, where O'Keeffe lived for most of the end of her life, is nearly inseparable from its "O'Keeffe country" sobriquet.

She was the first woman to have a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in 1946, and was awarded medals by two U.S. presidents during her lifetime. In the 1970s, she received revived national attention when feminist artists and art historians claimed her as a figurehead, but she refused to join their movement, rejecting the limited, gendered interpretation they gave her work. In 2014, her 1932 canvas

Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 achieved a world record by becoming the most expensive painting by a female artist ever sold at auction, for $44.4-million (U.S.).

Largely, what we think of her work is defined by three critical moments: when it was laden with Freudian innuendo by a group of men in the 1920s; when it was scorned by influential art critic Clement

Greenberg for being "little more than tinted photography" in 1946; and when it was co-opted by feminist art in the 1970s. All readings, so far, have been rather one-dimensional.

Certainly, her story is not that of the forgotten or overlooked female artist. But a visit to the Art Gallery of Ontario's sumptuous new retrospective in Toronto proves that such hypervisibility can, in fact, serve to obscure.

Look beyond the glittering accolades and salacious controversy swirling around this American icon and fuller, more nuanced and vivid picture emerges. By shifting the spotlight away from her overexposed flower studies, this exhibition shines light on the fact that O'Keeffe, one of art history's most well-known representational painters, was first and foremost a pioneering abstractionist.

Sky with Flat White Cloud, 1962.

g-williams/National Gallery of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

O'Keeffe had her first solo exhibition at just 29 and enjoyed sustained critical attention until she died in 1986, at a respectable 98 years old. Of the approximately 850 paintings that she created over her lifetime, the AGO exhibition has collected 80. It is thus the largest and most significant showing of O'Keeffe's work in Canada – ever. The paintings are supplemented by another 45 photographs, taken mostly by Alfred Stieglitz, her mentor, husband and reciprocal muse.

It was Stieglitz who gave O'Keeffe her first big break. He was 52 years old, a famous avant-garde photographer and owner of the best contemporary-art gallery in New York – this was 1916, before the Museum of Modern Art had opened and just a few years after the inaugural Armory Show. O'Keeffe was a 28-year-old art teacher, stationed alone in South Carolina and then the Texas Panhandle. Unbeknownst to her, a friend took a set of O'Keeffe's charcoal abstractions – imagine billows of black smoke, suspended at the apex of their surges – to show Stieglitz, who was immediately captivated, and started to exhibit her work at his gallery.

Two charcoal drawings at the beginning of the AGO exhibition signal this catalyst for O'Keeffe's fame. They're quiet works, muted in comparison to the sonorous ripples of pinks and blues that sing out from nearby paintings. But they contain proof that O'Keeffe, who was inspired by synesthesia, began experimenting with abstraction at an early stage. "I have things in my head that are not like what anyone has taught me," she once said, referring to the "shapes and ideas" that she felt only she had access to, and knew she had to figure out how to represent by herself.

Oriental Poppies, 1927.

Foto/The Collection of the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum

Unfortunately, her works were quickly ascribed a gendered meaning that she didn't intend. A wall of photographs in the exhibition by Stieglitz displays O'Keeffe's contemporaries in New York – mostly well-educated, privileged men. Feminist scholar and art historian Griselda Pollock has suggested that Stieglitz and his circle had a rehearsed strategy for promoting O'Keeffe's work. Basing their vocabulary on the Freudian theories popular in their intellectual milieu, they consciously lent sexualized readings to her paintings' vibrant curves and colours, writing, as Vanity Fair's Paul Rosenfeld did in 1922, that her perceptions were "utterly immediate, quivering and warm," and that "What men have always wanted to know and women to hide, this girl sets forth."

We might cringe at such descriptions now, but the group's motive was likely not sinister: The goal was to position O'Keeffe as the Great American Woman Artist, in the spirit of the group's collective modernist ambition to produce the Great American Play, the Great American Novel and so on. And it was achieved.

But it was not among them, in the big city, that she would find her place. Her paintings of New York are gritty, dark nocturnes, crowded with skyscrapers. At first, it feels impossible that O'Keeffe as we know her – queen of the stark, unpopulated desert vista – could have made such works, but that was exactly why she did. "The men decided they didn't want me to paint New York," she told The Atlantic in 1965. "I was furious!"

She's almost as famous for her indomitable spirit and impeccable sense of style as she is for her art, and the AGO does not disappoint in including exquisite black-and-white photographs of the artist made by her peers – including Ansel Adams, "her one, true friend," according to AGO curator Georgiana Uhlyarik.

It's a delight to check in with these beguiling portraits of O'Keeffe while moving through the various stations of her life. Her steely, discerning expression – once or twice collapsing into a disarmingly mischievous, dimpled smile – gradually becomes more furrowed, but is never treated to any cosmetic intervention other than perhaps a splash of cold water to the face, and a comb run once through hair that turns white as the decades pass. Her dress seldom wavers from a uniform of

blousy, white-linen shirtwaists layered under black cotton smocks, accessorized with a custom wire brooch made by Alexander Calder that spells simply, "OK."

Georgia O’Keeffe with watercolour paint box, 1918.

Alfred Stieglitz/George Eastman Museum

Tellingly, the 12 pictures of O'Keeffe selected from Stieglitz's

Portrait of a Woman, which comprises the 300 or so studies of her that became one of his life's major undertakings, are presented in a small, disconnected space.

The creative relationship between the couple was one of mutual admiration and inspiration, but by the end of it, when O'Keeffe was spending the bulk of her time away from New York – away from him – it devolved into competitiveness. He could be needy and controlling. Once, O'Keeffe shipped a box of bones from New Mexico to Lake George, Stieglitz's family's summer home in New York State, so that she could paint them while she was there. Before she got the chance to start her paintings, he made her sit for him and pose with the bones for one of his photographs.

Red and Yellow Cliffs, 1940.

Trujillo/The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

There is ample evidence that O'Keeffe used photographic principles herself as both technical and conceptual resources for compositions. One need only look at the prehistoric landscape Red Hills and Bones, from 1941, to see her debt to photography plainly evinced: A rack of bleached vertebrae, forced into close-up in the foreground, is in immediate, disorienting proximity to a wall of red rock in what should be the background of the scene. It's an effect that's difficult to see with the naked eye, but possible to capture with the right aperture setting on a camera.

In the layout of the AGO exhibition, Stieglitz doesn't appear again once O'Keeffe has shifted her life over to New Mexico. In real life, he never visited this place that she was so immersed in.

The weather and landscape of the Southwest enlivened her spirit. "Why, I've been so full of electricity," she wrote of the dry air's static, in a letter home to Stieglitz, "that my hair stands up straight – about three inches – when I comb it and my skirt cracks when I walk." It also painted her: "When I came back from a walk I'd be the colour of the road."

From the Faraway, Nearby, 1937.

Trujillo/The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

She bought two homes in New Mexico – Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu – and was consumed with painting abstracted versions of the region's vast, curving riverbeds, exuberant cottonwood trees, sloping, ochre-red canyons and pink-and-grey tablelands fragrant with sage and creosote bush. She picked up discarded, sun-bleached pelvis bones and used them as an aperture through which to isolate the patches of big, slow-moving sky that writer Willa Cather once described as "forever incapable of clouds." Some of her finest experiments in abstraction are found in her patio-door series, which prefigure similarly composed works by Ellsworth Kelly, Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Over and over again, she painted Pedernal, the sacred mountain that lorded over her "backyard." When she died, her ashes were scattered from it.

Through glass walls in her house at

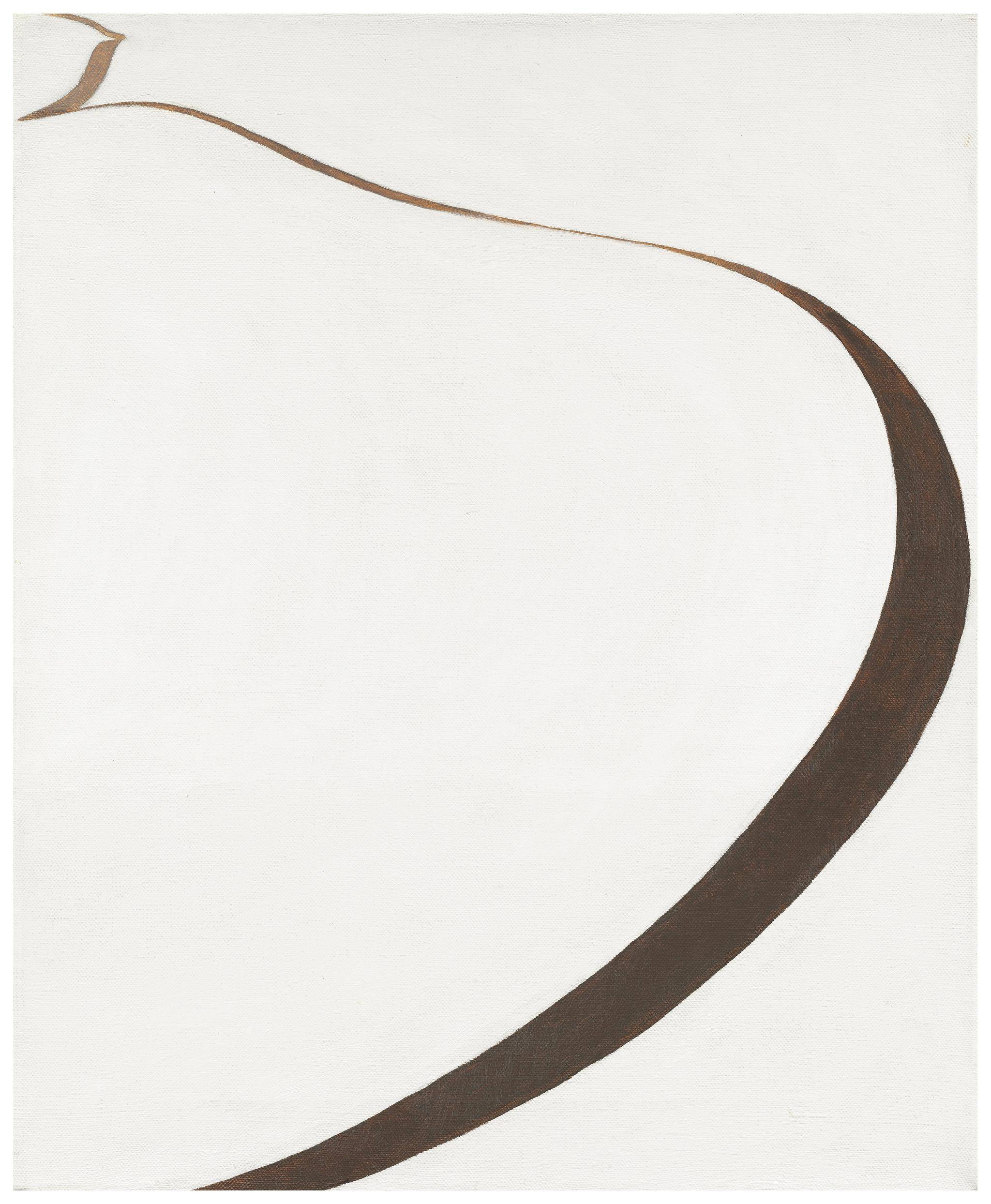

Abiquiu, O'Keeffe could see "the road to Española, Santa Fe and the world" stretching into the distance. In 1963, aided by photographic studies of the view that seemed to make the road stand upright, she painted Winter Road I. This is the last work you encounter in the AGO exhibition before entering the gift shop and its overflowing shelves of calendars, postcards and fridge magnets emblazoned with O'Keeffe's perennially popular blooms.

Winter Road I is small, about the dimensions of her charcoal abstractions from half a century earlier, but it contains multitudes. All extraneous detail has been eliminated. "The trees and mesa beside it were unimportant for that painting – it was just the road," she explained. Here is a clear example of O'Keeffe finding the form of those genderless, interior "shapes and ideas" that she sought for so long to capture. What remains on the paper-white surface of her canvas is a calligraphic swoop of burnt sienna – a purely abstract line, carved confidently, that excises all but the revolutionary spirit of a woman living by her own convictions.

Georgia O'Keeffe is at the Art Gallery of Ontario from April 22 to July 30 (ago.net).