In Of Montreal, Robert Everett-Green writes weekly about the people, places and events that make Montreal a distinctive cultural capital.

What did you do on your latest birthday? Did you hang out with friends and eat cake, or did you pore over old photos and learn more about your family history?

That’s the nub of a squabble arising over the events being planned to celebrate next year’s 375th anniversary of the founding of Montreal. On one side are those who want to make a big party, and on the other, those who are looking for a teaching moment.

I’m simplifying somewhat. Or rather, I’m summarizing the admittedly slanted view each of these sides has of the other.

The party crowd, for once, holds all the power. It’s led by Gilbert Rozon, “commissioner for celebrations” of the Society for the Celebration of Montreal’s 375th Anniversary. Rozon is best known as the founder of the Just for Laughs comedy festival, one of Montreal’s most successful entertainments. His interest in teaching moments can be gauged by looking at the committee he assembled to screen proposals for the anniversary, which doesn’t include a single historian. The committee’s evaluation criteria favour projects that fit with Rozon’s declared theme of “building bridges” and that are capable of showing clear touristic payback.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, proposals put forward by Montreal’s historical organizations have not been a hit with Rozon’s committee. Representatives of the Montreal Historical Society, the Château Ramezay museum and others aired their dismay recently in a front-page piece in Le Devoir. “The commemorative aspect is completely lacking,” said Frédéric Bastien, head of a group that represents Quebec’s history professors. Unflattering comparisons were made with Montreal’s 350th anniversary, now seen as a virtual golden era of civic remembering.

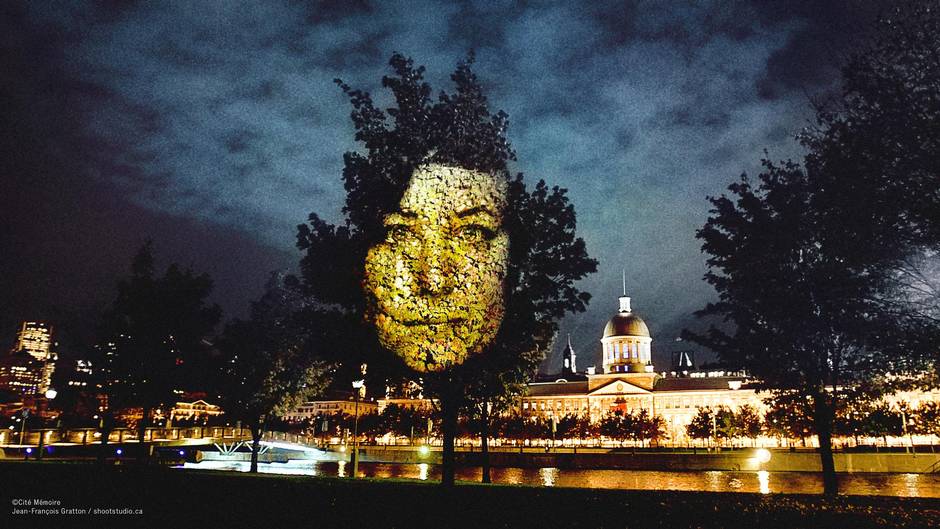

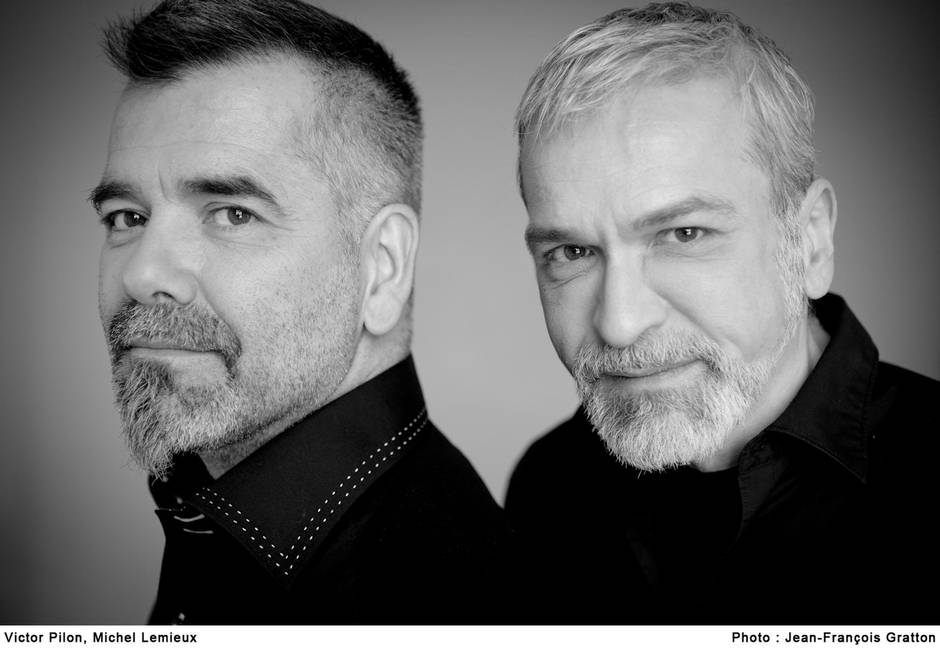

In Montreal, however, just about everything becomes more palatable if you can make a big projection out of it. That’s what Montréal en histoire has done with Cité Mémoire, a series of 15 projections “loosely inspired” by the town’s history, in continual nighttime rotation on buildings in Old Montreal. To sample the displays, created by Cirque du Soleil veterans Michel Lemieux and Victor Pilon, you walk to each site, trigger the related section of the Cité Mémoire smartphone app, and listen to the audio portion of whatever is flashing over the brickwork.

The subjects of these short dramas include the first prosecution for homosexuality in New France in 1648, the burning of Parliament by anglophone protesters in 1849 and the arrival of privately sponsored Jewish refugees during the Holocaust. There’s a segment about the city’s earliest movie house, and the funeral procession for Joe Beef (Charles McKiernan), a 19th-century taverner known for his good works and solidarity with the poor.

There are also daytime segments and “augmented reality” sections, for which you point your phone camera at a building and watch a clip-art animation about some relevant history on your screen. One of these augmented realities offers a laudatory history of the Bank of Montreal, which happens to be a major sponsor of Cité Mémoire.

The visual style of the projections will be familiar to anyone who has seen a Heritage Minute. The period costumes often seem to wear the actors, who are all a little too conscious of the historical point they have only a few minutes to make. Playwright Michel Marc Bouchard’s dramatic scenarios are sometimes effective, but the dialogue can be wooden. “The memory of a nation is burning,” intones a woman watching Parliament burn, sounding not at all like an early Victorian eyewitness.

Like Heritage Minutes, these mini-dramas often end with a sermon or a dollop of uplift. Beef’s cortège concludes with a reminder that the needy are still with us, as a van from the street-youth agency Dans la rue rolls into view. A black slave’s hanging in 1734 for a crime she may not have committed is fused with Jackie Robinson’s happier experience playing for the minor-league Montreal Royals in 1946. That theme of ever-increasing racial tolerance might be a tough sell in Montreal North, the scene of recent protests after another black man was fatally shot by police.

Unlike a Heritage Minute, Cité Mémoire requires you to get off the couch and follow a route through a part of town that can feel deserted at night. You have to be prepared to stand in empty parking lots and fumble with phone and ear buds. Not many were up for that on the warm evening I spent touring the sites. Often, I was the show’s only spectator.

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that the only aim of Cité Mémoire is to get people to do the full experience. This project doesn’t need your full participation to score in the ongoing effort to make Old Montreal a scene of nighttime spectacle. The quartier already has a dynamic and sometimes gaudy lighting policy, a sign of its determination not to be outshone by the projection-mad Quartier des Spectacles uptown.

In this scenario, it doesn’t much matter whether you download the Cité Mémoire app and press Play. Even as an unknowing passerby, you’re going to be affected by the sight of gigantic soldiers marching on a wall, or of a black woman running toward you from a raging house fire. A dark blank wall suddenly teems with life, and Old Montreal seems a more happening place. Without sound, this isn’t history, it’s Instagram writ large, a decontextualized stream of imagery that catches the eye and inserts a layer of photography between you and your surroundings.

Nothing wrong with that. But as Rozon might have said, it shows how hard it can be to bring a history lesson to a party. Even when the stories get told, in images three storeys high, there may be few following along.