Any time the Rolling Stones do something newsworthy – announce a gig in Cuba, release a new recording, publish a memoir, perform live – the professional journalist faces a terrible temptation in reporting the event: the temptation to lard his or her copy with allusions to classic Stones songs.

It’s an enticement best resisted, of course. Yet even now, some 54 years after Keith met Mick on that Dartford Station railway platform, it usually proves too alluring. Hence, the persistence of sentences such as this: “More than 20,000 fans got plenty of satisfaction last night as the Stones rolled to their emotional rescue with a 22-song set demonstrating these exiles on main street still can play with fire.”

I’m feeling a similar temptation as I type this. Recently, I visited the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, 45 kilometres northwest of Toronto, to look at a new exhibition of 50 photo-based works by Winnipeg’s Sarah Anne Johnson, inaugural winner, in 2008, of what is now the Aimia/AGO Photography Prize and a finalist for the 2011 Sobey Art Award. You could, I suppose, call them nature photographs since most were shot outdoors in the summer. But it’s an outdoors Tom Thomson, Lawren Harris and the other exalted ones whose work has so defined the McMichael might find a touch dismaying. Instead of the depopulated, sublime landscapes of the Group of Seven, Johnson’s milieux are filled with people, young people, alternately blissed and bummed-out on drugs, alcohol, 20 DJs a-turntablin’, 159 out-of-tune guitars, not to mention sleep deprivation, singalongs, marathon dancing and other rites of heroic hedonism. In short, we are talking about the world of the outdoor music festival, vividly rendered in all its glory and grot by Johnson in a presentation called … Field Trip.

Can you dig it? Field Trip! Field … trip! Even if the exhibition weren’t a good one (which it is) the temptation to go all Stonesy and run punnily amok with slangy references drawn from the sex-drugs-and-rock-’n’-roll lexicon is pretty much irresistible.

“Your mind will be blown.” “It’s a stoned soul pic-trip.” “Psych out at the McMike.” “High times by the Humber.” “The McMichael’s one can o’ bliss these days.”

I think, though, that I can resist. But if I do falter in the paragraphs ahead … well, blame it on the contact high.

Johnson, who is 40 this year, attended her first outdoor music whoop-up when she was 15. As bacchanals go, the Winnipeg Folk Festival may not rank high on the cosmic scale. But for Johnson, who says she had “a strict upbringing,” its three days and nights of partying and pacifism represented her “first taste of real freedom.” From that point, “I never stopped going,” she says, eventually taking in such gatherings as Burning Man (twice, the first in the late nineties, the last in 2008), Clearwater, Man.’s Harvest Moon, the Field and Shambhala, the last two in British Columbia. She started to photograph festivals in the late nineties, while earning an honours BFA at the University of Manitoba (in 2004 she was awarded a masters of photography from the Yale School of Art). “I just switched my intention,” she explains. “One year, I was there to have fun, the next, I went alone and worked. Still had fun, though! I love dancing and meeting new people.”

Johnson “love[s] taking pictures,” too, noting that “photography is the best medium to show what something looks like.”

At the same time, she’s gained a measure of fame for her discontent with the medium: It’s not good, she claims, for conveying “feelings or complex ideas.”

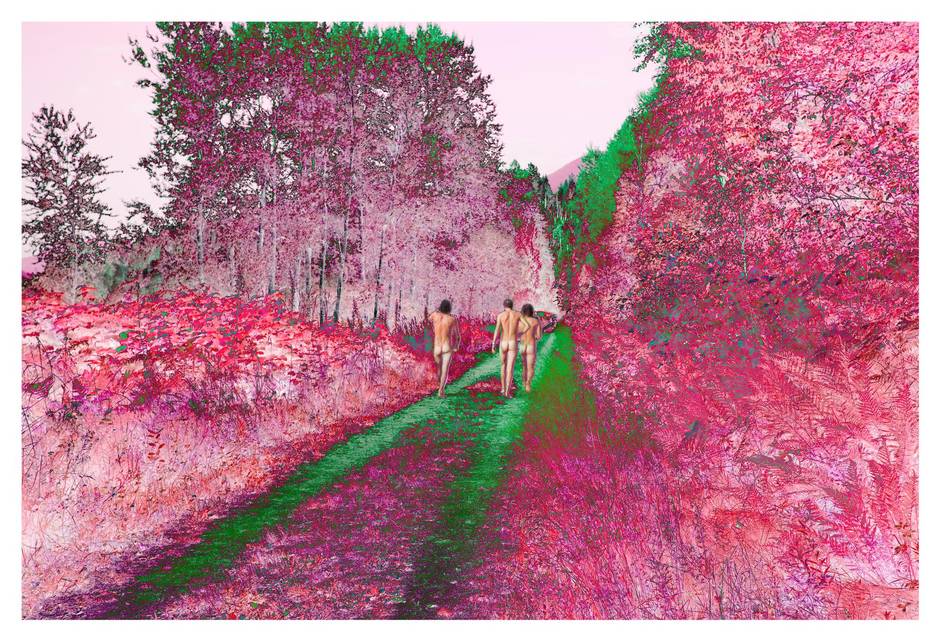

As a “solution,” she’s taken to working directly on her digital chromogenic prints’ surfaces with oil paint, acrylic ink, glitter and other augmentation materials, sometimes even incising the image field to strip out particular elements to give the picture depth. Photoshop is another tool.

As has often been mentioned about the Johnson oeuvre, utopia has been a major theme, perhaps the major theme since her 2005 debut exhibition Tree Planting (a series about young reforesters in northern Manitoba for which Johnson used not only photographs but dioramas and clay dolls).

So it is with Field Trip. Forget about pictures of celebrities and star performers; there are none. The emphasis here is on the People and the Scene and the attempt to fashion, however temporarily, a community or at least the feeling of a community free from the constraints and rhythms of workaday civilization.

Yet while Johnson is clearly a sympathetic participant-observer, she’s also honest enough to acknowledge the dystopic elements of the utopian enterprise. Outdoor festivals often are couched as celebrations of Mother Nature and our oneness with it, for example, but they’re decidedly hard on their setting – a fact Johnson unflinchingly conveys in a series of photos of all-too-human detritus (glow sticks, beer cans, condoms, phials, wrappers, liquor bottles). This awareness is expressed most apocalyptically in 2013’s Glitter Bomb, a large picture centred on a sparkly mushroom-shaped cloud rising skyward from the Hiroshima of a festival parking lot.

Johnson’s also keenly attuned to what might be called the psychic downside of the festival experience. Sometimes the drugs just don’t work. Or when they do, they’re freaky and they leave you feeling wiped out and alone, like the topsy-turvied narrator in Strawberry Fields Forever. Other times, the quest for non-stop ecstasy is simply too damn hard, creating an estrangement from the revellers around you. It’s a state rendered most creepily in a 2015 diptych of black-and-white pictures, Paranoia 1 and Paranoia 2, where a swarm of festival-goers, shot from above, have been given indistinguishable zomboid faces and featureless bug eyes (in Paranoia 1, the faces are white, in 2, black).

Meanwhile, Mess, with its protoplasmic explosions of psychedelic colour all but obliterating the human and naturalistic elements under them, essentially leaves it up to the viewer to decide: Is this Heaven? Or Hell? Or Heaven and Hell?

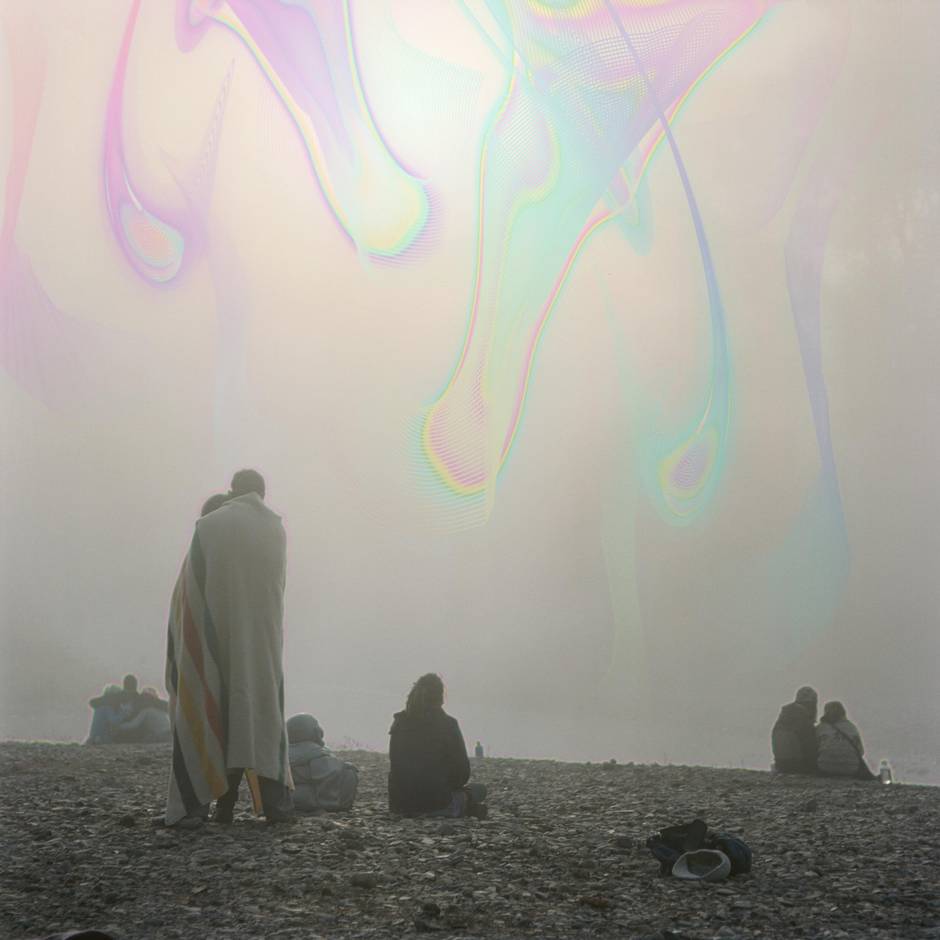

A bit of relief can be found with a picture such as Buddha Bay Blanket. Based on a non-digital photo from 2012, its depiction of people variously sitting and standing on a shoreline, backs to the camera, could be called a pastel pastoral – except that it’s a decidedly rocky beach and the pinkish vista so featureless (save for the soap bubbles Johnson has applied at the top of the image) that it can be read as much as an Antonioni-inspired scene of desolation as a post-psychedelic idyll. Still, I like its lack of frenzy. And, nostalgist that I can be sometimes, the image clearly is a homage to the famous Burk Uzzle photo used in 1970 on the Woodstock album cover.

Field Trip then is a treat for the retinas. Visitors will find it a busy one, too, as it’s been hung and strung in the McMichael’s spacious upper-level gallery where the collection’s log-and-caulk environment is very present. In other words, no soulless white walls here, tripsters.

Field Trip: Sarah Anne Johnson is at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ont., through June 5 (mcmichael.com). Hospital Hallway, a new series of performance-based video installations by Johnson, is running at the Division Gallery in Toronto through April 16.