The outward focus of today’s culture war is what Muslim women should be permitted to wear on their heads or at the beach. In the late 1980s, it was whether a publicly funded museum could show art that some elected officials considered obscene.

Robert Mapplethorpe was a key figure in that fracas, which peaked when Washington’s Corcoran Gallery of Art backed out of a touring exhibition of the American photographer’s works, and police raided Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Cente (CAC) for going ahead with it. The radioactivity of those events, which included an obscenity charge against CAC director Dennis Barrie, clouded discussion about Mapplethorpe for years afterward.

Now that we have burkinis to quarrel about, the art tempests of a quarter-century ago seem almost quaint. But Mapplethorpe’s photos still have the power to startle and even to shock, which is why the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts put part of its retrospective Focus: Perfection – Robert Mapplethorpe behind barriers of smoked glass.

Mapplethorpe, who died at 42, shortly before the Corcoran cancelled his show in 1989, would probably have been pleased to know that some of his work is still hot to handle. He often said, when talking about his shots of faceless men encased in vinyl or fisting each other, that part of what thrilled him about the gay porn magazines he saw while growing up in Queens, N.Y., was that their explicit contents were slightly hidden: inside a plastic cover, with black bars across the models’ eyes.

The current campaign to reset the discussion about Mapplethorpe began a decade ago with a couple of serious shows in Europe, and continues with the MMFA’s iteration of a joint double exhibition by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, drawn from a huge cache of works acquired by those institutions in 2011. An HBO documentary about the Getty/LACMA shows aired last spring, and production has started on a Mapplethorpe biopic, directed by Ondi Timoner and starring Matt Smith.

The exhibition’s position is that the culture wars of yesteryear should have no effect on Mapplethorpe’s stature as a colossus striding out of the bohemian haunts and seedy bars of 1970s New York. He was a master photographer, we’re told repeatedly, who “changed the field forever.” Like many shows that take the greatness of their subject for granted, this one doesn’t argue its case in detail. And while it insists that we place Mapplethorpe’s work in its social context, it doesn’t spend much time locating him within the art form he is supposed to have changed forever.

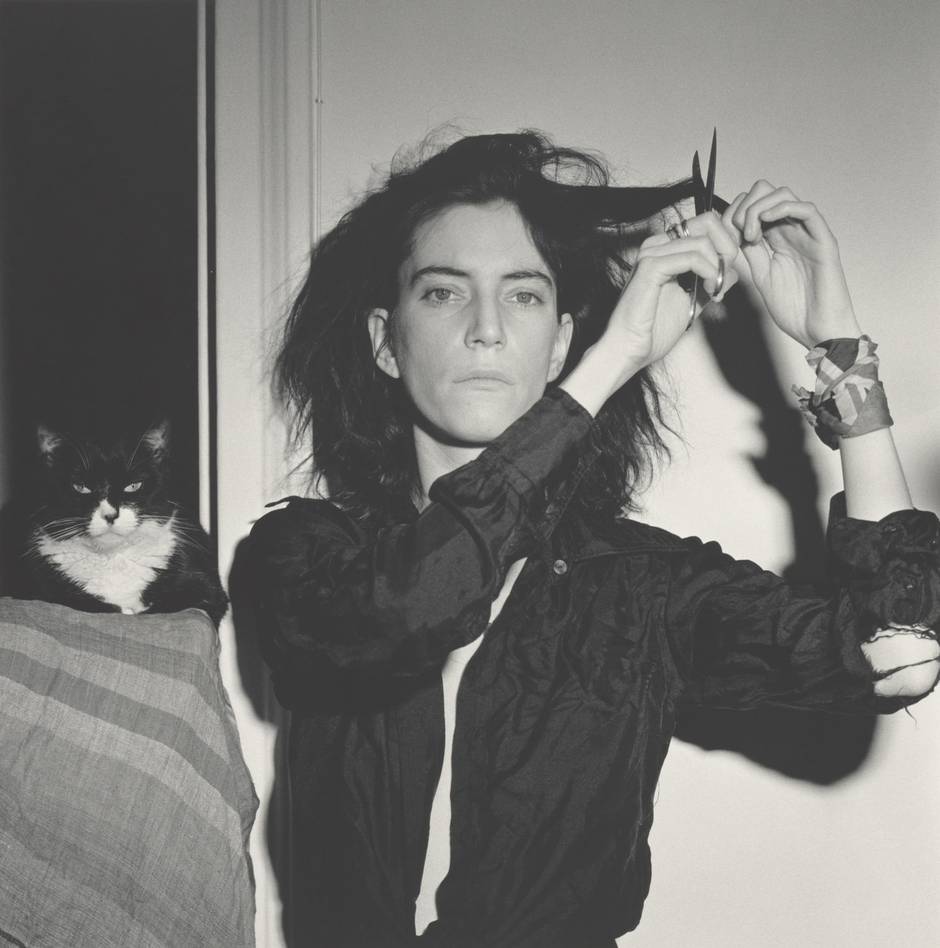

Mapplethorpe started taking pictures in the early 1970s, and within a few years had claimed his singular niche as a photographer of “faces, flowers and fetishes,” as one magazine put it in 1978. He insisted that he handled all his subject matter in the same way. “I don’t think there’s that much difference between a photograph of a fist up someone’s ass and a photograph of carnations in a bowl,” he said. The statement was meant to shock, and also to conceal: There are striking differences between, say, the portraits of his white celebrity friends and those of his black lovers.

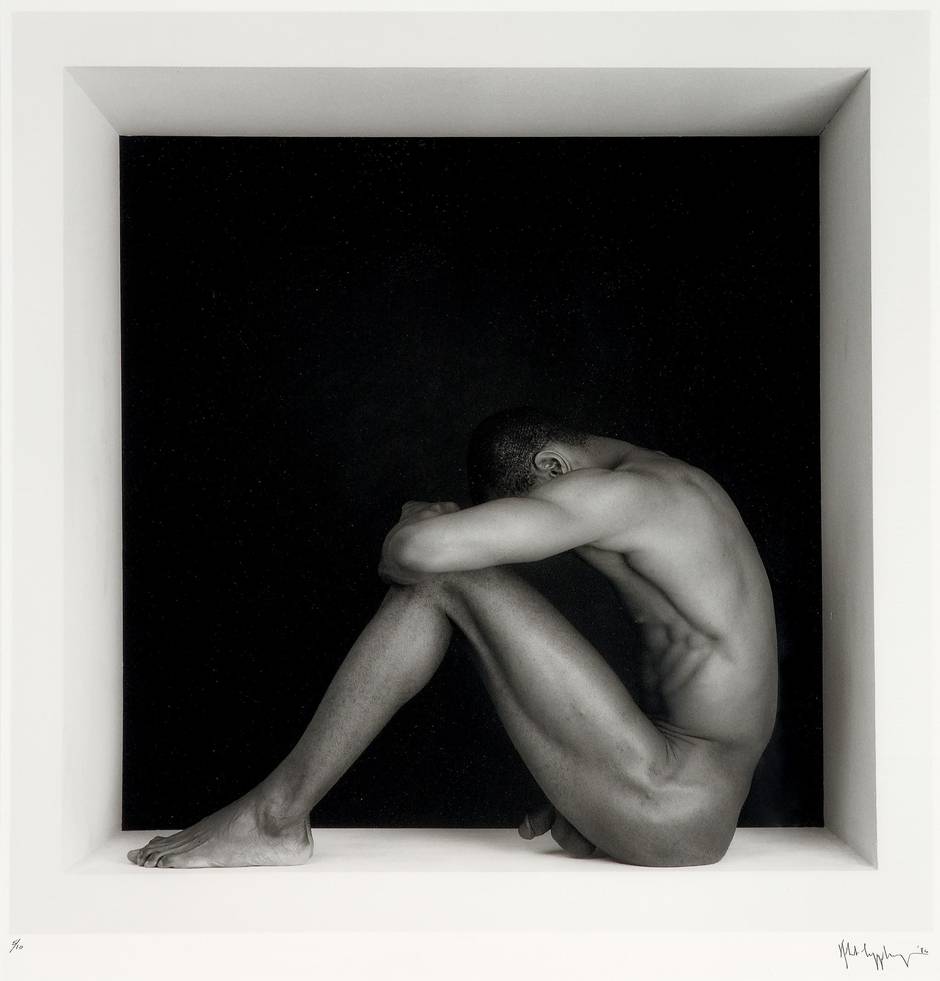

He also said that portraiture was about revealing personality, though this conventional stance played hard against Mapplethorpe’s determination to present the human form sculpturally. In a video loop shown in the exhibition, we see him giving a young shirtless model many subtle directions about the exact positioning of his body, but not a word about how he should look. The body was treated like sculptor’s clay, but the face was left to the model’s own discretion.

The big caveat is that almost everyone in Mapplethorpe’s square portraits looks cool and self-possessed (The exceptions are the children, who look innocent and objectified). There are no shots of people looking fragile, silly or uncertain, just as there are no bodies in his sex photos that show flab or a merely average-sized penis. Mapplethorpe had a definite idea about how those in his photographic world should look, and enforced it relentlessly.

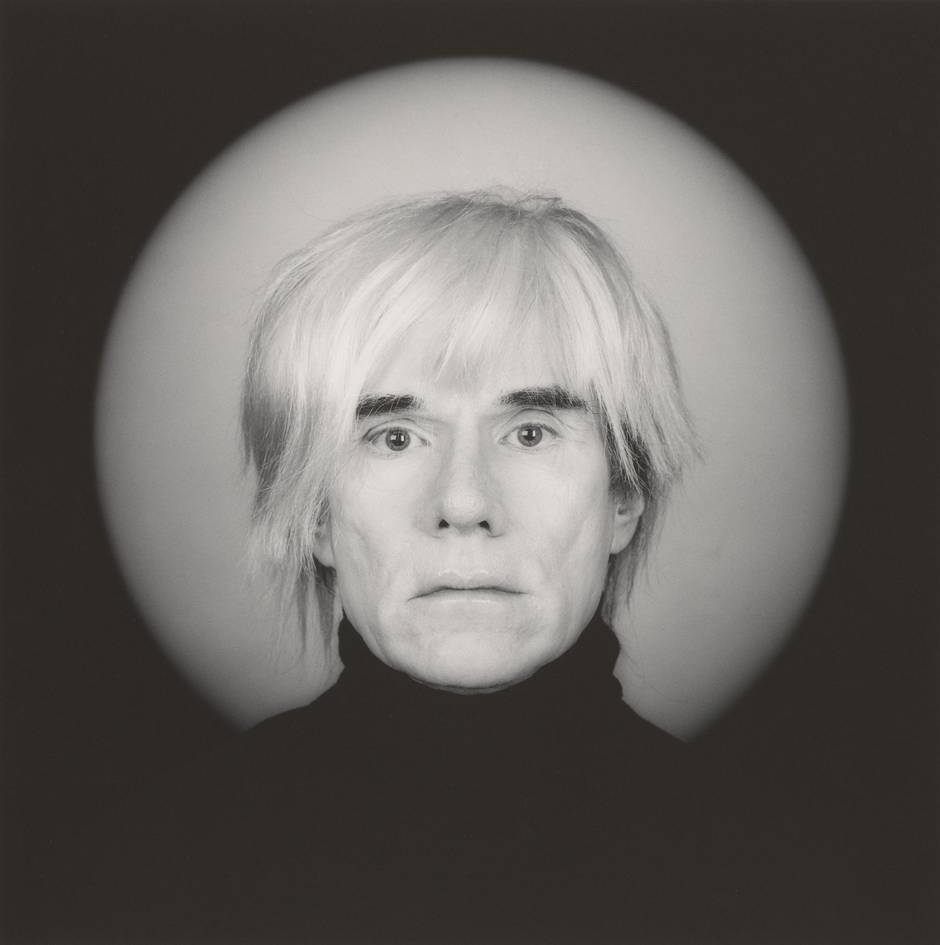

Compare that to the practice of Peter Hujar, another New York photographer who had built a portfolio of square portraits of downtown drag queens before Mapplethorpe shot his first S&M photo. Hujar’s people expose their imperfections and display their personalities in ways that are foreign to the godlike sculptural figures chilling in Mapplethorpe’s photos. Of course, part of the downtown culture of New York at the time was devoted to being cool and showing it. Mapplethorpe was a faithful chronicler of that scene: Andy Warhol was much more his type of subject than, say, Harvey Fierstein.

Mapplethorpe’s coldness is often linked to his eye for the classical, which was examined in depth by a 2014 exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum. Mapplethorpe’s classicism was austere but also theatrical, which is why the curators of that show brilliantly chose to align him with the overheated classicism of 16th-century mannerist prints, not the more restrained forms of ancient Greece and Rome.

Mapplethorpe was definitely influenced by the monochrome whiteness of Roman statuary. It shows in many of his portraits, especially of women: Isabella Rossellini, Lucy Ferry and Yoko Ono, who looks as chalky as a geisha. Then there’s Robert Sherman, who appears in a famous double head shot with Ken Moody. Both men have alopecia areata, an autoimmune condition that made them perfectly hairless, heightening the contrast between Moody’s black skin and Sherman’s apparent albinism. But Sherman, who appeared at the MMFA’s media launch, isn’t an albino; Mapplethorpe bleached him out photographically, to emphasize Moody’s blackness.

The show makes no attempt to relate Mapplethorpe’s work to previous photography, apart from including a dozen easily missable images by Diane Arbus, George Platt Lynes and Ansel Adams, a landscape specialist presumably chosen for his devotion to exquisite composition and lighting.

One photographer who came unexpectedly to mind as I toured the show was the fashion photographer Horst P. Horst, who received a major retrospective at Montreal’s McCord Museum last winter. Like Horst, Mapplethorpe had a sculptural imagination and preferred to work in a studio where he could control all aspects of lighting and background. A series of his flower images from the late 1970s, and some of the sex photos, use a dramatic night-world lighting similar to what Horst perfected in his shots of gowned models and naked men.

Unlike Horst and most other serious photographers, Mapplethorpe had little interest in technique, relying on others to develop and print his negatives and even to light his subjects. The silliest grand claim made by the show’s curators is that he was “a master of the black-and-white square-format gelatin silver print,” which is like calling Jeff Koons a master of all the fabrication processes he pays others to perform. Mapplethorpe was more like an executive producer of photography, who guided and selected what was made in his studio.

His two most absorbing subjects, for me, are Lisa Lyon and black men. Lyon, with her bodybuilder’s physique and strong symmetrical face, was the perfectly ambiguous sculptural object: feminine and masculine at once, equally compelling as a nude, a nun, a languid movie queen or a woman made to look like a man in drag.

The black men hold my eye because they so often embody Mapplethorpe’s penchant for racialist objectification. In his catalogue remarks about Hooded Man, a shot of a well-hung black nude with a bag over his head, art historian Jonathan D. Katz muses on lynching imagery, saying that the image comes “perilously close to repeating the racist equation of black masculinity and the fantasy of the ‘big black dick.’” According to Mapplethorpe’s biographer Patricia Morrisroe, he liked to call his black bed mates “nigger.” The show chooses not to lift that lid.

It might have been interesting to enlist some contemporary black artists to respond to this side of Mapplethorpe’s work. The MMFA featured a pointed foray of that sort in its Orientalism exhibition last year, displaying work by Middle Eastern women artists that challenged the show’s 19th-century portraits of passively exotic Arab women.

But this show isn’t really about finding new angles on its subject. It’s about reviving Mapplethorpe for people old enough to feel a kind of reverse nostalgia for the culture wars of the 1980s, and for those too young to remember. The L.A. curators who put it together (assisted in Montreal by the MMFA’s Diane Charbonneau) seem less eager to make waves than to jack up the profile of an artist who has become one of their museums’ marquee attractions. That’s a very Mapplethorpe move, because one thing he craved above all was personal fame. Focus: Branding might have made a good subtitle.

Focus: Perfection – Robert Mapplethorpe continues at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts through Jan. 22 (mbam.qc.ca/en/).