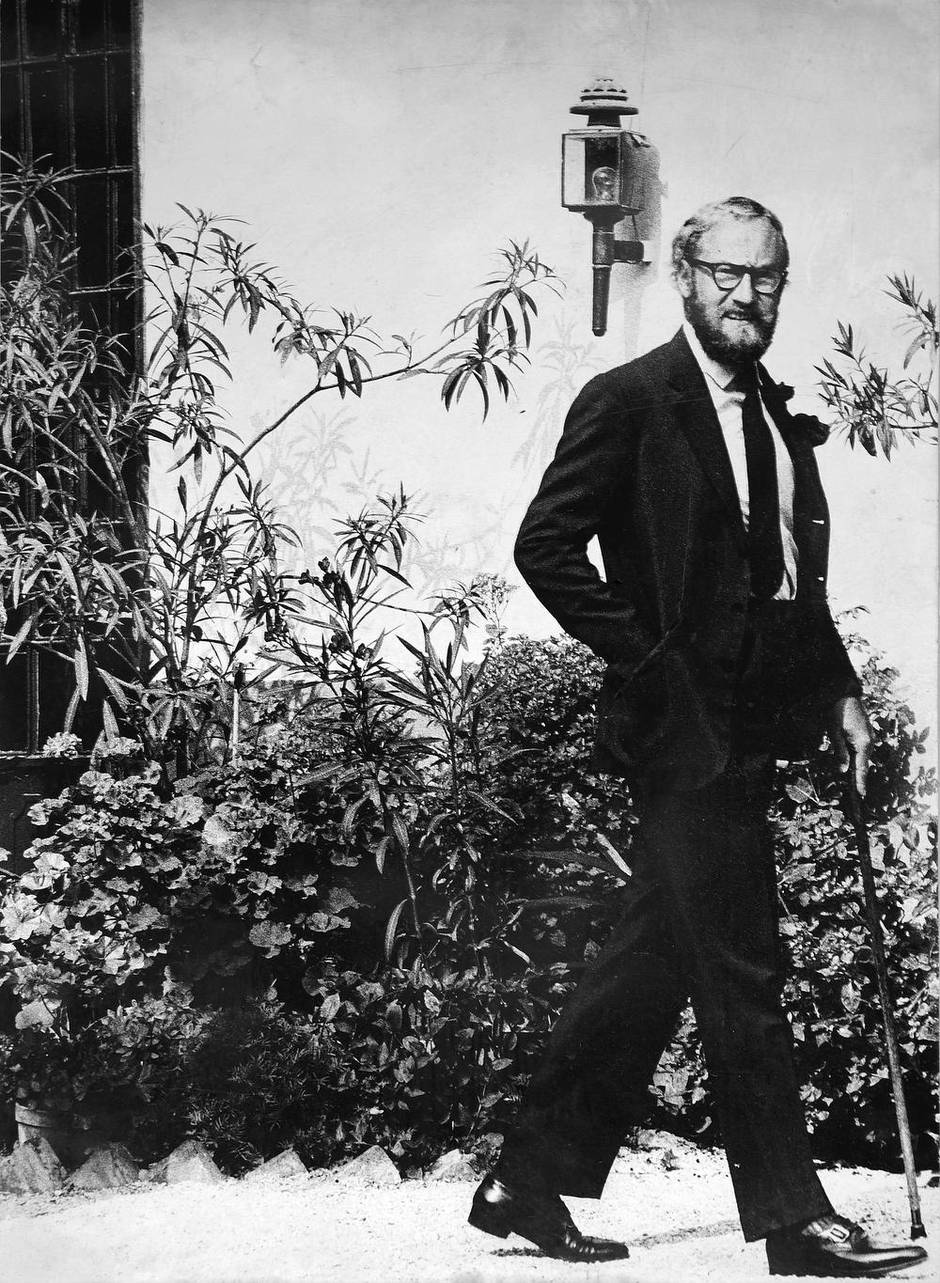

Peter Stephen Winkworth was a secretive man, not given to interviews, public pronouncements or autobiographical outpourings. So it’s unknown just how attuned he was to life’s perversities, how keen a sense of irony he’d developed by the time he died at 76 in 2005.

We can, however, be ironists on his behalf, and make this case: that the loss by Winkworth of a leg to a motorboat’s propeller in an accident on the Monte Carlo shoreline in the mid-1950s proved a significant, even unprecedented gain for Canadian culture.

For it was in the 50 years following that mishap that Winkworth did his greatest work – you could even call it the work of history – namely the accumulation of the most extensive private collection of Canadiana ever: thousands of vintage prints, maps, drawings, tomes, ceramics, glassware, charts and ephemera relating to first European contact and colonial history in the 18th and 19th centuries. Today Winkworth’s most important artifacts reside, permanently, in Ottawa, in Library and Archives Canada and the National Gallery, the result of two headline-making, multimillion-dollar deals completed in 2002 and 2008 after years of tortuous negotiations.

Not everything Winkworthian, though, has vanished behind the doors of institutions. On April 1, 249-year-old auctioneer Christie’s in London is hosting a sale of more than 300 lots of (mostly) Canadiana culled from the armoires, cabinets, mantles and walls of the now-sold Kensington mansion Winkworth and his late wife, Franca, occupied for 50 years. Interest is “huge,” says Brett Sherlock, a Christie’s senior vice-president based in Toronto. And so might be the prices hammered down.

The lots – which include some 25 wares commemorating Major-General James Wolfe’s death on the Plains of Abraham in 1759 and an early 19th-century tomahawk/pipe that once belonged to a governor-general – are going into the bidding carrying a total estimate of $1.7-million to $2.5-million. But with individual collectors and museums circling along with a reported consortium of Canadian public institutions, the final tally could be much higher.

Back briefly to the accident in Monte Carlo. Certainly it was tragic, Winkworth’s existential dividing line. But if you’re inclined to a literary view of life, you could say that until it occurred, Peter Winkworth was living the life you’d expect of the London-born son of an affluent English father and an indulgent Canadian mother. Raised in Britain until he was 7, when his businessman father died, he was sent to Quebec where he eventually attended Bishop’s College School in Lennoxville, east of Montreal. After high school, he read history at Wadham College, Oxford, before joining a firm of Canadian stockbrokers and financial consultants in London. Slender, handsome, adept at tennis and rowing, he cut, according to several reports, a most elegant figure.

Collecting seems to have been in the Winkworth blood. A grandfather and an uncle in Britain, for example, had large appetites for Chinese porcelain and furniture. Winkworth himself was fond of the prints of the English caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827), and some time in Winkworth’s late teens, an uncle in Paris either sold or gave him a set of early 19th-century colonial-era prints by Maj.-Gen. James Pattison Cockburn, from his two tours of duty to Upper and Lower Canada.

Accounts vary as to how avid was Winkworth’s collecting impulse initially, how destined he was to become a full-time connoisseur and acquirer of things. At the same time, there is no denying his avidity gained in mania, momentum and volume after the events in Monte Carlo, including, the Daily Telegraph reports, the court case that “won him a then-record sum in compensation for his injury.” Sent to New York to recuperate, Winkworth reportedly practised the use of his artificial leg by walking up and down the daunting entrance stairs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He pored over catalogues and monographs, attended auctions, visited antique shops. Somehow he got Harry Shaw Newman, famed proprietor of New York’s The Old Print Shop, to take him on a six-week tour of Europe where he was introduced to contacts and shown the tricks of the trade.

Certainly it was smart of Winkworth to fix his passion on Canadiana; as historian Charlotte Gray has written, “Canadian prints and drawings were considered of little value” in the late 1940s into the 1950s, even among Canadian museums. Socially well-connected in Britain, he would purchase material from both dealers and households, often “visiting,” observes Gray, “the country homes of families whose forebears had served in Canada as military officers or government officials to ask whether they had albums or sketchbooks they were interested in selling.” Much of the material had “lain untouched in attics since it had crossed the Atlantic more than a century earlier.”

As Dennis Reid, former chief curator of the Art Gallery of Ontario, remarked in 2009: “Peter, I think in many cases, was there before us” – “us” being Canadian museums and galleries. It wasn’t until the 1970s that they began to play catch-up. Or at least tried to.

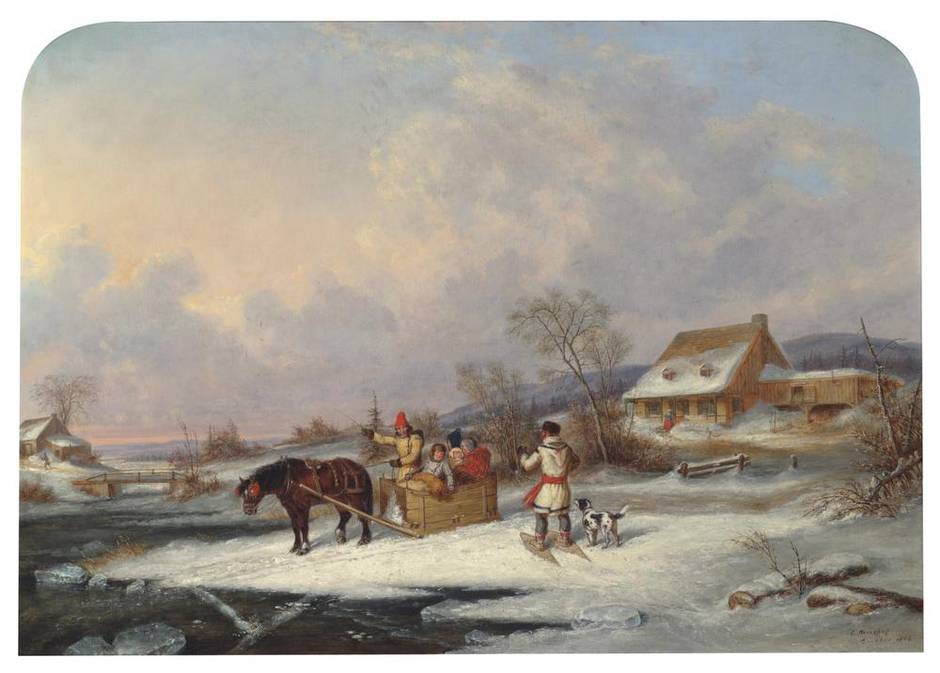

Compared with the prices fetched by some modern and contemporary art, Canadiana, especially 19th-century historical works, still seems like a bargain. A superb 1856 Cornelius Krieghoff canvas, Quebec Farm, for example, carries the highest estimate – $115,000-$154,000 (£60,000-£80,000) – of any lot in Christie’s Winkworth sale.

Yet for Nicholas Lambourn, Christie’s head of department, topographical pictures, it seems like 1981 all over again. That’s the year he started at Christie’s in London and watched billionaire Canadian collector Kenneth Thomson at auction fend off Toronto art dealer G. Blair Lang to acquire, for £85,000, a Krieghoff, Moose Hunters (1859), that had been consigned by Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester. “That was the world record for a Canadian picture in 1981,” Lambourn recalled during a recent promotional/preview visit to Toronto (the painting is now at the AGO in Toronto). “So in sterling terms, Krieghoff hasn’t moved very much.” The auction record for a Krieghoff, $490,000, was set more than 20 years ago, and the market has been largely dormant ever since.

Still, Lambourn thinks “there’s a lot of interest coming back into this field. Certainly it’s highly prized by institutions.” Take the Winkworth cachet, the fact he rarely lent works from his collection while alive, add the obvious quality of Quebec Farm and “I think you can see why we’re hoping the end result will far exceed what we got for Moose Hunters.”

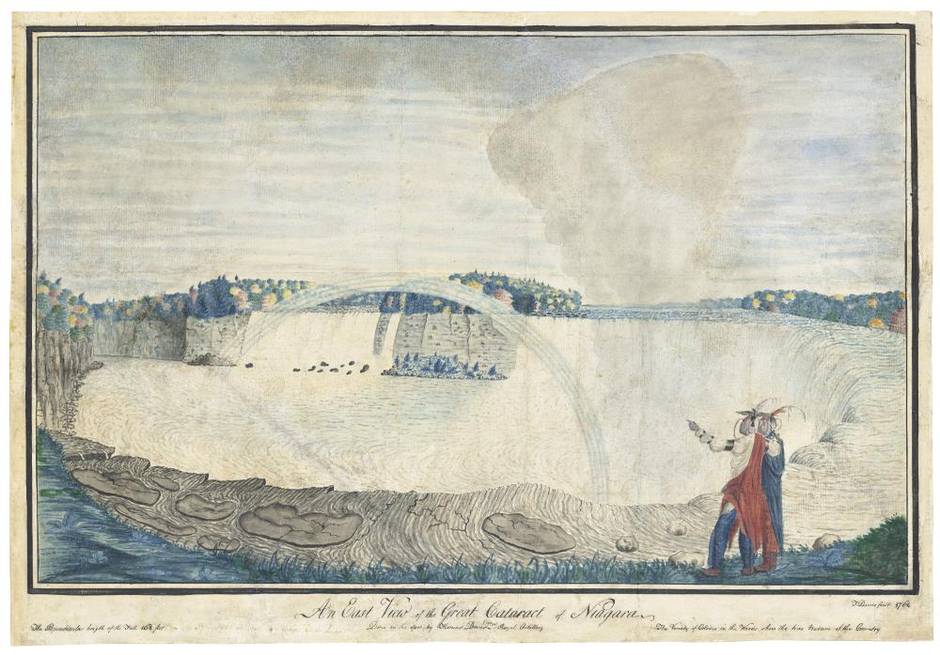

Two other lots are exciting Christie’s. One is a watercolour on paper, titled An East View of the Great Cataract of Niagara, painted in 1762 by the British army officer/collector/historian Thomas Davies. A gripping panorama, it’s generally regarded as “the very first view of Niagara Falls taken on the spot and the first accurate view … radically correcting earlier fanciful descriptions.”

So keen is Christie’s on the Davies that, upon landing in Toronto earlier this month, Lambourn and fellow Christie’s colleagues Nicolas Martineau and Helena Ingham travelled to Niagara to stand on the exact spot where the soldier composed his view. Christie’s presale estimate for the Great Cataract is $77,000-$115,000 (£40,000-£60,000). But Martineau is convinced it will fetch more since Christie’s, in the 1980s, sold “an incredibly rare” view of New York by the same artist for £110,000, “and this Niagara view is just as interesting.”

Martineau is bullish, too, on the lot featured on the front of the auction catalogue. Untitled, by an unknown painter and dated to the early 19th century, it’s a vivid depiction, in oils, of Mi’kmaq hunters camped on a bay somewhere in Nova Scotia or New Brunswick. Calling it “a magical picture,” Martineau describes its concentration of “iconic symbols” as almost an archetype of “what people think of when they think of Canada – teepees, Mi’kmaqs, Canada geese, canoes.” A similar-sized canvas of the same scene by the same artist is in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Canada, but Christie’s says its “lovely thing,” 44 centimetres by 60, has the better condition. It’s being sold as a package with another, same-sized canvas of a related scene by the same unattributed artist. The estimate: $46,750-$74,800.

By the time the auction ends Wednesday afternoon at Christie’s sales room on London’s Old Brompton Road, Lambourn says it is likely that 95 per cent of the lots sold will have been bought by Canadians, the remainder going to U.S., British and possibly French collectors. And while the room is expected to be full of bidders and interested observers, “it really doesn’t matter where a sale is held these days,” Lambourn said. “Everything’s global. We can sell Australian art in London to Australians in Australia. They can just sit on their yachts with their laptops and bid live.”

The auction of The Winkworth Collection: A Treasure House of Canadiana occurs at Christie’s South Kensington (London) branch April 1 starting at 8 a.m. ET, 12:00 noon GMT.