In February, 2015, neurologist Oliver Sacks – arguably the world's best-known brain doctor and the greatest physician writer in English, wrote an article in The New York Times called My Own Life, announcing that "my luck has run out."

Dr. Sacks, 81 years old, still wildly productive, clear-headed, feeling robust, and swimming a mile a day, had just found out he had multiple metastases, from an ocular cancer that had been treated nine years before. One-third of his liver was filled with cancer.

No sooner had he shared his ill fortune than did he begin to write of his gratitude for the years he had been granted since his original diagnosis, and his overall feeling of gratitude for having lived as "a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet … "

Hardly a word more was said about the cancer. For now, face to face with dying, he was not quite done with living. He would restrict himself to essentials, which meant saying goodbye to dear friends and family, and continuing to write as he always had, hoping to die "in harness."

A group of short, extraordinarily affecting essays followed, his farewell to the world, leaving many readers in tears. Dr. Sacks's specialty had been documenting how an individual, trapped in an extreme mental state that altered perception and even identity, retained his humanity. How, one wondered, might Dr. Sacks bear up when facing his own ultimate transformation?

There were surprises, and some revelations, too, in these lyrical meditations, which have been gathered together in a very short book collection – called, fittingly, Gratitude, which appeared on Nov. 24, not long after the release of his memoir, On The Move.

The essays in Gratitude had a spare beauty about them – unusual for a writer who so loved the rich tangent. They were unique among his other, more lush, scientific writings. They had the feel of wisdom literature. Wisdom sifts; a wise man, mindful that he has little time to say what he must, gets to the point.

And the tone was unusual. They were both stoical and poignant. These are two qualities that rarely go together; we tend to think of stoicism as a kind of armour worn against our emotions, and poignancy as the breaking through, into our stream of consciousness, of emotions, even our most tender and delicate feelings. The poignancy and stoicism of the Gratitude essays was heightened by Dr. Sacks's reiteration that he was an atheist. He was, as far as he knew, facing a total erasure of his identity.

Instead of "battling" his illness, the common metaphor of such accounts, he accepted that he was going to die. And his attitude, in Gratitude, is ultimately to see dying – odd as it is to say it – as an opportunity, of sorts. His burgeoning awareness that his life is ending is affording him a vision of it he had not had before. "Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as sort of a landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts."

The final essay concluded: "And now, weak, short of breath, my once-firm muscles melted away by cancer, I find my thoughts, increasingly, not on the supernatural or spiritual but on what is meant by living a good and worthwhile life – achieving a sense of peace within oneself. I find my thoughts drifting to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and perhaps the seventh day of one's life as well, when one can feel that one's work is done, and one may, in good conscience, rest."

Most readers came to Dr. Sacks far sooner though, through his medical writing, which had always been a literary event as well as a scientific one. W.H. Auden called his second book, Awakenings, a "masterpiece." The prominent literary critic Frank Kermode wrote of it, "This doctor's report … is written in prose of such beauty that you might well look in vain for its equal among living practitioners of belles letters." But he was also a physician's physician, and when he died, the surgeon Atul Gawande wrote in The New Yorker, "No one taught me more about how to be a doctor than Oliver Sacks." This Dr. Gawande gleaned not from working with Dr. Sacks at the bedside, but from reading him.

Dr. Sacks saw himself as a naturalist, cut loose within the world of medicine, and naturalists love to collect, catalogue, describe and discern, in great detail, the manifold variations in nature. Dr. Sacks was wedded to the proposition that we learn best from a close study of the particular. He hated textbooks, with their generalizations and remote language, and science by committee. He wrote to vivify each patient's unique experience, often using their own idiosyncratic speech. He listened not only with a stethoscope, but a poet's ear.

Thus Dr. Sacks's writing required a plentiful prose. He never used just one adjective when he could use many; he loved crisscrossing between case reports written centuries and continents apart; and his footnotes grew like vines from the bottom of the page upward with each subsequent edition. He hid treasures in those footnotes that could be more intriguing than those found in the main text.

Gratitude, such a personal book, might seem but a non-medical footnote to Dr. Sacks's medical career. But that makes sense if we see medicine as only about "cures" – and dying as something it needn't concern itself with. In these final essays Dr. Sacks took as his primary subject the case of Oliver Sacks himself, in the process of dying, to teach us something about how to die.

Oliver Sacks's legacy was to restore a vision of a humane medicine that drew its power not from technological breakthroughs alone, but through the healing power of the doctor-patient relationship. It had roots in a more old-fashioned view that came in part from his general-practitioner father, who had close relationships with his patients and did frequent house calls. It was a form of care that required an almost unheard-of immersion in the lives of his patients by Dr. Sacks, which allowed him to draw portraits of human beings of an incomparable subtlety and sensitivity, while shedding new light on the mysteries of the brain. He also rejuvenated for us the rich tradition of the case history.

Yet Dr. Sacks's triumph did not come immediately or without opposition.

"[W]ith little encouragement from my colleagues," he wrote, "… I became a storyteller at a time when medical narrative was almost extinct. … It was a lonely but deeply satisfying, almost monkish existence that I was to lead for many years."

It may sound a strange claim, but the detailed case history – which in the 19th century produced some of the finest descriptions of patients ever written – had all but disappeared from the neurology journals when Dr. Sacks started writing, and, even today, it is rare. The great 19th-century neurologists, lacking scans, EEGs, and statistics, perfected their observational skills and the art of talking to patients so as to help them describe how those patients' mental experiences were altered by their brain problems.

With the advent of modern lab and scanning techniques, these observational and communicative skills atrophied. The journals changed, too. Detailed accounts of individual patients increasingly disappeared, replaced by group studies of "subjects," described in more abstract, statistical terms, based on their scans and scores on tests. Instead of reporting what was unique about a patient, studies reported what was average about a population. And averages smear out what is unique about individuals.

And if an individual patient was described, it was often in a several-sentence anecdote – not to be confused with a detailed case history. If anything, the anecdote was intentionally nondescript, suppressing personal details, because it focused not on the person with the disease, but the disease itself. To some tastes, this made the anecdote seem more "scientific." After all, a diagnosis describes a disease, something that is supposed to be fairly invariant from person to person. A diagnosis is what a group of people have in common, not what distinguishes them from each other.

In this frame of mind, the mental life of the person with the illness is a distraction.

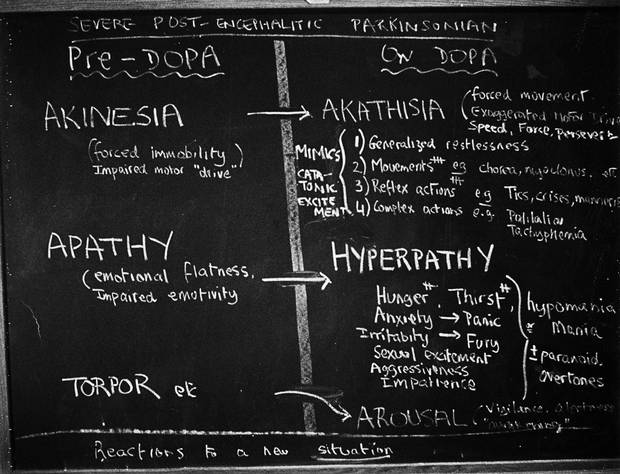

One of Oliver Sacks’s many “think boards” from his Awakenings days.

Oliver Sacks's breakthrough book was based on his work at a backward chronic-care hospital, Beth Abraham, in the Bronx. It was the kind of place conventionally ambitious physicians avoided. There he discovered about 80 patients who had suffered an illness called encephalitis lethargica, which left them, after a period of great nervous excitement, with "sleeping sickness," often frozen in fixed postures, like "living statues," mute and unable to move. An earlier physician had described them as "extinct volcanoes." Sometimes, even their thought processes were in a kind of suspended animation. They had been this way for four decades.

To understand these often mute patients, Dr. Sacks totally immersed himself in their lives, moved into the hospital on-call apartment, and took call every night for almost four years, after working his regular 16-hour days. Over time, he began to sort out their individual characters, and noted that they had Parkinson's disease-like symptoms. He eventually discovered they responded to a new drug, L-dopa.

Former "statues" turned into 1920s-era flappers, and danced together. Though many were pushing 70, they felt as if they were in their twenties, and spoke using phrases, affectations and accents of their youth. Their faces seemed to confirm that suspension of time: Immobile and expressionless for so long, they hadn't formed wrinkles.

His first five medical reports, describing their profoundly moving and dramatic "awakenings" on the drug, received very positive responses when published in major medical journals, such as The Lancet and the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Less well known, but a crucial spur to his development as a thinker and clinician, was what happened after. Dr. Sacks reported that, within months, his patients experienced major side effects on L-dopa, and cautioned that maybe these people were sensitive "canaries in the coal mine," and that L-dopa might best be used with caution on more typical Parkinson's patients. He was viciously attacked. Some said he was "off his head," and that no such side effects occurred.

When he tried to publish a systematic study of these "side effects" (which he thought were really "effects" of the drug) in the same medical journals that had published his first findings, and others, he was refused.

Dr. Sacks was struck by how his colleagues, though they thought of themselves as scientists, were using almost religious language, describing L-dopa as a "miracle drug." And so he began to psychoanalyze how yearnings drive longings in doctors and patients alike, and colour our views of medication, treatment, and, indeed, the whole world of illness.

He published his findings in 1973, not in a medical journal, but in a book meant for anyone who was interested: Awakenings. As years passed, and the side effects Dr. Sacks observed were seen by others, the book became a classic with the lay public and neurologists alike, and was adapted into a well-known film, but not before he was fired for daring to question authority, and told by his boss to vacate the on-call apartment at Beth Abraham, depriving him of his home, his job – and, most important, his regular access to his patients.

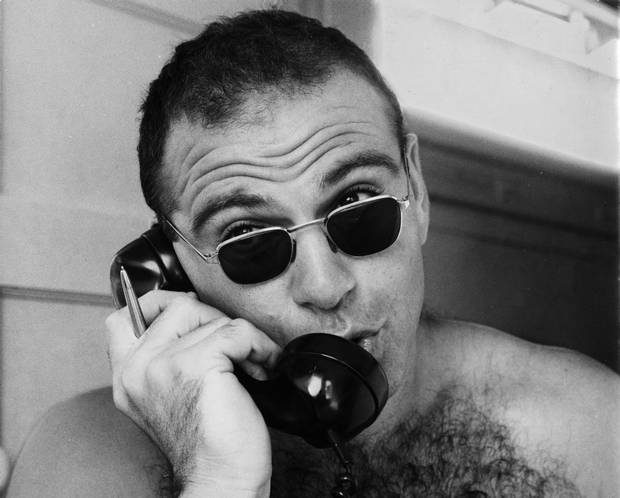

Dr. Sacks in New York circa 1970.

Awakenings became a success, but it wasn't until 12 years later, when The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat came out, that Dr. Sacks became a bestselling author.

Hat, as his friends came to call it, explains how discrete localized brain problems lead to very specific changes in mental experience. The "man" of the title, Dr. P., a music teacher, had a lesion in a specific visual area of the brain. The most famous scene in the book begins when Dr. P., believing that Dr. Sacks had just finished examining him, "started to look around for his hat. He reached out his hand and took hold of his wife's head, tried to lift it off, to put it on. … His wife looked as if she was used to such things." When Dr. P. was walking in the street he would, somewhat Magoo-like, genially "pat the heads of water-hydrants and parking-meters, taking these to be the heads of children."

If Awakenings was a feverish, tidal book, overwhelming with its stories of living death, resurrection, and living death returned, Hat was a more classical one: multiple, bite-sized clinical tales, written with great charm, about how brain problems lead to losses, or excesses, of mental activity.

Hat's preface included powerful arguments for why case histories are every bit as medically important as studies.

The idea of the case history goes back to ancient Greece, and Hippocrates, who first wrote about diseases having a course, a way of unfolding in time. Doctors began to write "histories" of their patients' illnesses, essentially biographies of disease, but, Dr. Sacks argued, they were really "pathographies" – documentations of the illnesses themselves, in which the human subjects largely disappeared.

Dr. Sacks argued that this convention was no longer sufficient, and wrote, "To restore the human subject at the centre – the suffering, afflicted, fighting human subject – we must deepen a case history to a narrative or tale." These clinical tales, like classical fables, "have archetypal figures – heroes, victims, martyrs, warriors," because "patients are all of these," and more, "travellers to unimaginable lands."

This restoration of the person to the centre was especially, and obviously, necessary for neurology, psychology and psychiatry, Dr. Sacks wrote in Hat, "for here the patient's personhood is essentially involved, and the study of disease and identity cannot be disjoined."

The strongest single influence on Dr. Sacks's idea of how to develop these whimsical-sounding "clinical tales" was the Russian scientist Alexandr Luria (1902-77). It was from Dr. Luria that Dr. Sacks got the inspiration and the model that would allow him to make the case history his major focus.

Dr. Luria, as a very young man, was a major contributor to the development of psychoanalysis in his country, and corresponded about the subject with Sigmund Freud – who was originally a neurologist, and who, according to Dr. Sacks, wrote "matchless case-histories." Dr. Luria was drawn to analysis because it was, as far as he knew, the only branch of psychology that took both materialist science and human subjectivity seriously.

But this was not to last. In the late 1920s, under Joseph Stalin, psychoanalysis was decreed "politically incorrect." One month after giving a sympathetic lecture on Freud's thought, Dr. Luria, fearing for his survival, publicly renounced his ideological "mistake," and abruptly resigned from the Russian Psychoanalytical Society. He went off to medical school, and reinvented himself, pioneering the field of neuropsychology and the study of the higher cortical functions of the brain. He published conventional monographs and treatises.

But in private letters to Dr. Sacks, in 1976, Dr. Luria made clear that he still took psychoanalysis seriously, and in one he offered a psychoanalytic interpretation of one of Dr. Sacks's neurological patients. Though he had disavowed his commitment to analysis, Dr. Luria had been writing up neurological case histories in the detailed manner of Freud, in secret, for decades.

When Dr. Sacks first read one of these book-length cases, Dr. Luria's The Mind of a Mnemonist, in 1968 (about a Russian with an almost perfect memory who made his living performing feats on stage, but who was also deeply tormented because he could not, like most people, automatically forget unimportant events), Dr. Sacks thought it must have been a novel, Dr. Luria had so well described the man's unusual subjective experience.

When he realized it was non-fiction, Dr. Sacks was so filled with admiration that he also became overwhelmed with fear, thinking, "[W]hat place is there for me in the world? Luria has already seen, said, written, and thought anything I can ever say, or write, or think." Dr. Sacks was so upset that he tore the library copy he was reading in two – then, getting a hold of himself, went out and bought one replacement copy for the library, and one for himself.

Verbatim: Oliver Sacks on the art of writing

Dr. Sacks credits that book with altering the course of his life. The next summer, he wrote the first nine case histories of Awakenings. Dr. Luria, to whom the book was dedicated, was delighted, and wrote to Dr. Sacks that the kind of approach taken in Awakenings "is lost now, perhaps because of the basic mistake that mechanical and electrical devices can replace the study of personality."

With "the advent of the new instrumentation," technology was getting between the physician and the patient. "The physicians of our time, having a battery of auxiliary laboratory aids and tests, frequently overlook clinical reality."

This would seem an extreme statement; after all, why must new technological tools lead to a loss of clinical reality? Can we not have both? Can one not enhance the other? And yet, Dr. Luria, according to Dr. Sacks, believed that there was a "conceptual and emotional atmosphere" that came with technology that cast a shadow over the doctor-patient relationship.

This occurs, I would argue, because technology is not simply something we use; it comes part and parcel with a particular medical theory and practice.

Modern scientific medicine has taken a fundamentally materialist approach, and it is "analytical," meaning that it divides wholes into parts. It often proceeds by reducing complex phenomena to their more elementary chemical and physical components: viruses, genes, molecules, and so on. Our technology measures these elements. That is what we do when we determine that a patient has a fever and trouble breathing because her lung is infected with microscopic bacteria.

In psychology, this materialist theory aims to reduce all psychological phenomena to physiological laws of how the brain works. The goal is ultimately to build up abstract models of the brain, based on the observation of its individual elements.

But, Dr. Luria worried, "One outcome of this approach is the reduction of living reality with all its richness of detail to abstract schemas." Dr. Luria wanted to restore the whole patient to scientific papers, and leave aside the abstractions, and even, he confessed, the description of personality with statistics. Can we human beings be understood solely in terms of our elements, our molecules, atoms, our parts, our circuits, our reflexes, even our behaviours? Or must not all of it be understood as part of a whole experience, which would include, of course, the subjective, qualitative mental experiences and intentions that drive behaviour?

This was not a dry debate about how to report science, but about a profound philosophical difference. When Dr. Luria was a young man, he presented his first book, The Nature of Human Conflicts (1932), which aimed to be both objective but also to report on cases in detail, to the pre-eminent Russian psychologist Ivan Pavlov, inventor of behaviourism. A day later, when Dr. Luria met him, the old man's eyes were blazing, and he tore the book in half and threw it to the ground, roaring, "You call this science! Science proceeds from elementary parts and builds up; here you are describing behaviour as a whole!" Dr. Luria was declared "un-Pavlovian" and "un-Soviet," and had to keep his extensive case histories in the drawer for about 30 years before daring to publish them, and only after having first published many standard group studies and treatises.

Group studies look at aspects of people: For instance, they select scores on tests, and compare them. One would think that a larger study would always trump a single case study. But group studies, like case histories, have both strengths and weaknesses.

Dr. Sacks wrote that "all sorts of generalizations are made possible by dealing with populations [group studies] – but one needs the concrete, the particular, the personal too, and it is impossible to convey the nature and impact of any neurological condition without entering and describing the lives of individual patients."

Case histories are the only place in the medical literature where we see, if not the whole patient, at least enough to get a picture of a living human being.

Case histories can make hundreds of observations about a few people, and thus may not be representative of the larger population; group studies on the other hand, make a few observations about many people. The question is: Is it possible to understand a person with a brain illness, by describing him or her in bits and pieces – by observing just a few variables?

The assumption underlying the typical group study of a disease is that each participant has the same disease, and that any variation between them – whether they exercise, for instance, or have other genetic risk factors or psychological issues – is relatively insignificant. This assumption of uniformity certainly doesn't hold when talking about the brain, which is so complex, and differs extensively from person to person. As well, no two brain injuries are identical, and usually affect different brain areas.

This tremendous variation between patients is probably one key contributor to a problem that has now been acknowledged as a major one in the life and medical sciences: the replication crisis.

One would have to have lived in a cave within a cave for the last 10 years not to have noticed that many key medical findings from group studies are being reversed, almost monthly – be it studies on the usefulness of mammograms and prostate tests, or the effectiveness of various medications. Many of the finest randomized controlled trials (RCTs), we are now learning, cannot be replicated. Worse, most published group studies in medicine can't be reproduced, leading to what Europe's premier science journal, Nature, now calls "the reproducibility crisis."

A study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association in 2014 showed that 35 per cent of the conclusions of the finest RCTs, assessed by peer review and published in the most respected medical journals, cannot be replicated on reanalysis of their raw data. And the most downloaded article in the history of the journal PLOS Medicine, appearing in 2005 and called Why Most Published Research Findings Are False, showed how bias easily sneaks into data analysis. This has led Nature to call for new methods to try to eliminate bias in medicine and life sciences.

Thus, there is less safety in numbers in these fields than we might wish. (I take no pleasure in this, as one who writes on life sciences.) This is why we need to be open to a range of study methods, both single case studies and group studies.

As for the retort that case histories are not "scientific" because they are not "quantitative" – that confuses statistics, one tool of science, with science itself. Francis Crick, who, after co-discovering DNA, turned his attention to the problem of consciousness, eagerly pored over the Sacks case histories in draft form. He did so knowing, as neurologist and neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran explains: "[I]n neurology, most of the major discoveries that have withstood the test of time were, in fact, based initially on single case studies and demonstrations."

Our views of what constitutes rigour in science depend on the paradigm of the day. A paradigm is a theory – with associated laws, practices, and related technological and analytical tools – about an aspect of the universe.

Statistical paradigms dispense with non-statistical technologies. But changing from one form of technology to another has unintended consequences. True, we don't tend to think of the case-history report as a technology. But I would argue that it is, and that the technology that underlies the case history is not just writing, but language itself – an invented medium that allows us to put our thoughts and subjective experiences into words. And, so far, it is the best medium we have for becoming aware of and conveying private experiences. Language, though ancient, is not less sophisticated for being old, but more, having been refined over millennia. When the subject we are studying is the nature of human experience itself, this is not technology we can dispense with.

The language we use for the doctor-patient encounter affects the nature of that very relationship. The word "patient" comes from the root for "one who suffers" and it goes best with another old-fashioned word: physician or, heaven forbid, healer. But these words – the language of medicine for centuries – are increasingly being swept away by impersonal technological terms, which manage to be bland and hideously undignified at the same time: terms like "medical-system user" and "health-care systems provider."

The language of "user" and provider" masks the fundamental insight in the word "patient." When we are truly sick, we are suffering, dependent, and not wholly ourselves. We require a "healer" (which comes from the old English haelan, which means not simply to "cure" but to "make whole"). We require not just a provider of goods and services but also a relationship we can trust.

Our remote, obfuscating language is a pathetic replacement for a vanishing, highly personal healer-patient relationship, an ancient archetype that is being buried. People can feel stripped of their dignity, autonomy and personhood on entering such user-provider "systems." The logistical demands of those systems, along with the presence of devices such as computers, can directly intrude into the doctor-patient relationship. Physicians, compelled by numerous pressures from the "health-care efficiency experts," must spend as much time looking at their screens during eight-minute visits as at their patients.

Increasingly, clinics and hospitals treat clinicians as interchangeable "service providers." Once we enter such a system, to make up for the loss of my doctor or my nurse, we are assured we now have something better: "the team." Doctors and nurses may come and go, but the team will always be there. But will a team with interchangeable members we may barely know really have our back in a crisis, really care about us, as much as someone with whom we have an ongoing relationship?

All this systems-oriented care – an oxymoron – is not simply the product of underfunding health care. It occurs in nations rich and poor, capitalist and socialist. Rather, it grows out of a paradigm that sees the world of illness and health solely in material, analytical, statistical and technological terms.

Against this, how we long for an old-fashioned, irreplaceable Dr. Sacks, taking call every night, with his two-hour assessments of "his" patients. For in a world in which the doctor is too easily replaced, so too, we sense, is the patient.

Dr. Sacks seeing patients at Beth Abraham, 1988.

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985) was based on the prevailing view of its time, one built up over the 19th and most of the 20th centuries, that the brain was made up of several hundred little "organs," each of which had a genetically preassigned task. The adult brain was fixed. The great triumph of that era of neurology and neuroscience was to begin to map the brain, localizing where each of these areas were.

Hat gave readers a first tour through these little organs, while also describing the human drama of how these patients were affected by their malfunctions and misfortunes. These were stories, as Dr. Sacks saw it, of patients who either lost their identity because of a brain lesion, or who triumphed and found a way to preserve that identity.

In the late 1980s, however, neuroscience underwent a major shift. With the increasing recognition of neuroplasticity – the discovery that even the adult brain's physical structure is adaptable and can change in response to experience – Dr. Sacks realized that Hat was based on a partially outmoded view of the brain.

Clinically, he was beginning to observe that neuroplasticity was at work in people with neurological disease, as they adjusted to their illnesses.

In his book An Anthropologist on Mars (1995), he showed how, owing to "the brain's remarkable plasticity," illness could even "play a paradoxical role, by bringing out latent powers, developments, evolutions, forms of life, that might never be seen, or even be imaginable, in their absence."

To learn of these evolutions, he left his office and spent time with patients as they worked, travelled, and lived their lives. He explored savant-like skills in autistic people; how tumours or strokes might give rise to new ways of seeing the world. No longer was Dr. Sacks seeing his suffering patients as either losing their identity, or preserving it; these were instead all stories of the metamorphosis of identity. In most of the cases, he made sophisticated psychoanalytic observations about how the mental life and the neurological problems interacted, pushing for a more holistic neurology.

Dr. Sacks used his understanding of plasticity not to try to cure, alter or improve the people he was writing about. His purpose was to understand, to appreciate, how the human spirit changed in response to brain changes.

Anthropologist is the book where Dr. Sacks achieves staggering heights, and shows he has no peer. I know of no better, more subtly observed, eye-opening case histories in 20th-century neurology.

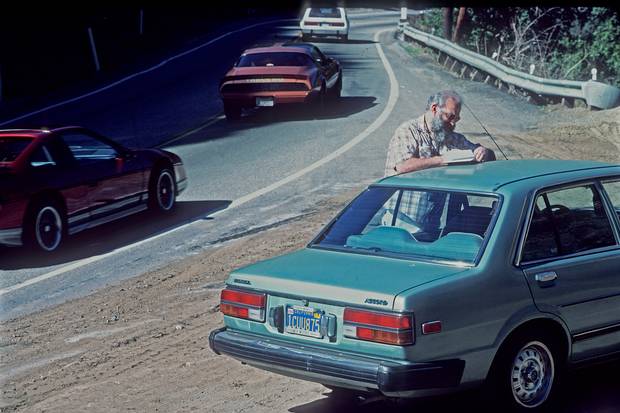

Dr. Sacks writing on a car roof.

I met Oliver Dr. Sacks only once, in the spring of 2008.

Zarela Martinez, a dynamic New York restaurateur, was the author of a book on the food and life of her native Oaxaca. Oliver had written Oaxaca Journal, his own exploration of southern Mexico, especially its ferns (he was an amateur pteridologist), and when he learned of Zarela, he showed up at her restaurant one day, asking her to autograph his copy of her book. A friendship ensued.

Some time later Zarela contacted me: Coming across Dr. Sacks's endorsement of my first book, she had bought it, and then got in touch because she was using some of the neuroplasticity principles I described to help minimize the onslaught of her own Parkinson's symptoms.

Upon learning that Oliver and I had never met, Zarela became excited ("Another excuse for a party!") and organized a small dinner at her house. It was intimate, with my wife, Karen; Zarela; her partner, Jamie (a retired adult-film actor); Oliver; James Watson, the Nobel laureate and co-discoverer of DNA; and Dr. Watson's wife, Liz. I had previously dined with Francis Crick, of Watson and Crick, and Dr. Sacks had been close with Dr. Crick, but neither of us had ever met Dr. Watson until that evening. This assortment of guests was typical of a Zarela get-together, and comfortable for Dr. Sacks: His own eclectic circle could bring together an astronaut, a dental hygienist, a fern expert, a car dealer, several Nobel laureates, and the person who scrubbed his floors.

She sat Oliver and me together. I wanted to thank him for what his writings meant to me, and for what he had done for me personally. When the manuscript of my first book was complete, it was sent out to many people for comment. He was the only one to respond, remarkable in a man with so many demands on his time. (I say this as someone who has not always managed to do the same for others myself.)

I expressed my heartfelt gratitude; he was warm, but self-minimizing, in a British way. As we dug into the dinner, and discussed current projects, the naturalist emerged. He discoursed, like a botanist, on our salad, but not all vegetables, I learned, were equal: He had a particular passion for radishes, and he carefully singled them out from the other, leafy things on his plate.

He was, I had been told by a colleague who studied with him as a resident, painfully shy, and I remember, more than anything, the slowly unfolding pace of our conversation. He spoke softly, was attentive, tactful, gentle, and utterly unlike some of the wound-up wordsmiths and intellectuals from the brilliant Oxford set of his university days.

We settled into our orbit, found our range and roster of shared interests, and the conversation proceeded from a mutual interest in Russian literature (he raised Oblomov, the lead character in Ivan Goncherov's novel, about a man who got nothing done), to Dr. Luria and mutual professional challenges, including keeping up with correspondence. Dr. Sacks received thousands of letters. "The worst," he said, with distress, "are those who write hoping for magic."

Toward the end of the evening, he told me, with some pride and tenderness, and in a nod to the fact that I was also a psychoanalyst, that he had to go, because he had an appointment with his own analyst in the morning. "We've been seeing each other for a long time."

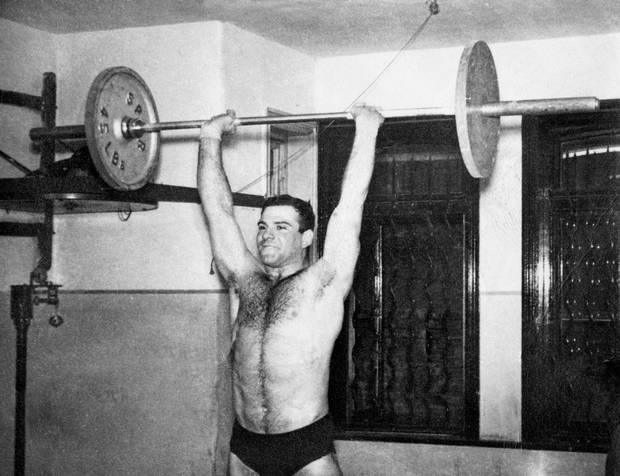

Lifting weights as a novice at the Maccabi club in London, 1956.

Oliver Sacks had a good start in life, born in London to a loving, Orthodox Jewish family, immediately followed by a very traumatic childhood, which he wrote about in a first memoir, Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (2001). During the Nazi bombing of London, six-year-old Oliver was evacuated, with his brother, to a boarding school called Braefield, in the Midlands.

The headmaster beat all the boys; he beat Oliver on his bottom till the cane broke, and sent Oliver's parents the bill for the cane. The older boys soon beat the youngest among them. He was often hungry, and survived mostly on turnips and coarse beetroots for cattle, because the matron stole the food parcels his parents sent. His parents, both physicians, busy in London with war duties, could only rarely visit. In the four years he was a student at Braefield, he was allowed to visit home only once. He felt abandoned, betrayed, desolate and hopeless. His belief in God was shaken. "He always said," Kate Edgar, Dr. Sacks's assistant and close friend, told me, "that the exile to boarding school was the major wound in his life."

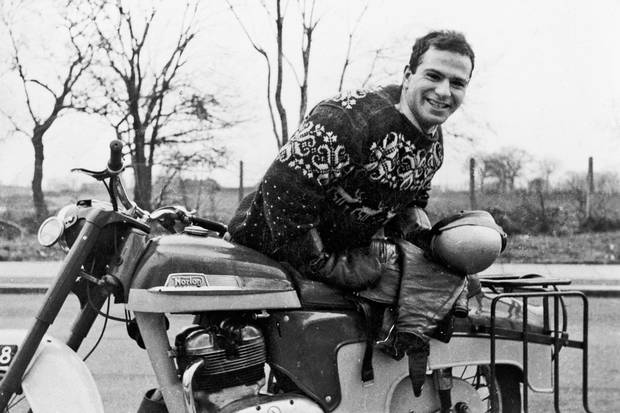

To survive Braefield, Oliver took refuge in numbers, thinking about them, manipulating them, exploring mathematical relationships. When the war ended, this evolved into an interest in chemistry. He also went from being a well-behaved child to acting out – he came home utterly changed. When he wasn't replicating the major experiments of modern chemistry, he loved making explosions and noxious gases ("bangs and stinks," as he called them). His teacher wrote in his school report, "Sacks will go far, if he doesn't go too far." As an adolescent, he became a serious motorcyclist.

The mild-mannered man I dined with wrote, "I cannot say (nor would anyone who knows me say) that I am a man of mild disposition. On the contrary, I am a man of vehement disposition, and extreme immoderation in all my passions."

Braefield was not the only agony from his youth. When he was 18, Oliver, questioned by his father, acknowledged that he had sexual feelings for boys. "Don't tell Ma," Oliver said, "she won't be able to take it." His father did tell her, though, and when she saw Oliver, she said, "You are an abomination. I wish you had never been born." It was never discussed again.

He later wrote, "My mother, so open and supportive in most ways, was harsh and inflexible in this area." It was, probably, all the more agonizing because his relationship with her remained, until she died, his most important. As he wrote in On the Move, "My mother's death was the most devastating loss of my life – the loss of the deepest and perhaps, in some sense, the realest relation of my life."

Ultimately, he was forgiving. "We are all creatures of our upbringings, our cultures, our times. And I have needed to remind myself, repeatedly, that my mother was born in the 1890s, and had an Orthodox upbringing and that in England in the 1950s homosexual behaviour was treated not only as a perversion but as a criminal offence."

Torn by conflicted feelings, Oliver had to lead a furtive romantic life through his 20s, when he had several love affairs.

Oliver Sacks with his new 250cc Norton motorbike in 1956.

Oliver became a combination of an intellectual and a renegade. He studied medicine in Britain and then made his way to North America, crisscrossing the continent on a motorcycle, and getting into some dangerous accidents. He briefly spent some time hanging out with Hells Angels, biked across Canada, and tried to sign up as a pilot with the Royal Canadian Air Force. He later moved to California, where he set a state-wide weightlifting record, and also began a medical residency in neurology.

At the end of work on Friday, he'd exchange his white coat for leathers, and the "Wolf" (his middle name) would come out, wanting speed, adventure, risk and novelty, and he'd ride his motorcycle, sometimes all night, to the Grand Canyon, to catch the sunrise. He'd ride back all Sunday night, for medical rounds Monday morning.

Arriving in the United States, in the 1960s, his deep interest in both chemistry and the mind drew him to try many different kinds of mind-altering drugs. Many of his weightlifting friends used speed and he did, too. Driving his use was deep emotional distress: His drug use escalated after a soured love affair. "I craved some deeper connection – 'meaning' – in my life, and it was the absence of this, I think, that drew me into near-suicidal addiction to amphetamines … "

By this point many of Dr. Sacks's friends had died on amphetamines. He was, often, "half-psychotic" and emaciated. One New Year's Eve, high on the drug, he had a lucid moment: "Oliver, you will not see another New Year's Day, unless you get help."

Dr. Sacks started undergoing psychoanalysis in 1966, "knowing I would not survive without help." Stoned much of the time, he realized Dr. Leonard Shengold, his analyst, could both pierce his defences, and "not be deflected by my glibness." Dr. Shengold got him off drugs, so the real analytic work could begin, and taught him "about paying attention, listening, to what lies beyond consciousness or words." Dr. Sacks wrote of his analysis, "I think it saved my life many times over."

Verbatim: Oliver Sacks on his experience with drug use

One of the most remarkable things about Oliver is that, though he is known as such a deeply sensitive writer and person, it was not always so.

Among his friends was poet Thom Gunn; they often exchanged manuscripts. After praising a draft of Awakenings, Mr. Gunn felt he could now reveal his true feelings about Dr. Sacks's early diary writings, and wrote to him: "I found you so talented, but so deficient in one quality – just the most important quality – call it humanity, or sympathy, or something like that. And, frankly, I despaired of your ever becoming a good writer, because I didn't see how one could be taught such a quality. … Your deficiency of empathy made for a limitation of your observation. … What was deficient in these writings is now the supreme organizer of Awakenings … I wonder if you know what happened."

He had learned to empathize.

Dr. Sacks was thrilled by the letter, and spent a long time pondering how he had changed. Was it that he had fallen in and out of love? Was it his attachment to his patients? Or a drug experience that opened him up to great empathy? He concluded that "psychoanalysis had played a crucial role in allowing me to develop."

People in analysis frequently do develop more empathy for others, by several circuitous routes. Most commonly, they learn which of their own disowned, repudiated or repressed feelings they routinely project onto others. Once these projections are cleared away, they can actually take a far better look at others, and determine what they may be feeling.

As well, people who have undergone long-term, severe traumas survive them by cutting off their own feelings – dissociating them, and becoming numbed – or by forgetting. One thing Dr. Sacks unearthed during his analysis, for instance: His parents did visit him at Braefield, though he had no memories of it.

Dr. Sacks had another unusual problem, one that he believed underlay his shyness, but that may well have affected his ability to empathize: a rare neurological condition called "face-blindness" (technically, congenital prosopagnosia).

It meant that the processor in his brain that normally analyzes differences between faces never developed properly. Throughout his life, he could not recognize acquaintances or friends.

Dr. Sacks's face-blindness was profound. Once, he apologized for bumping into a large, bearded man, only to recognize that the man was himself in a mirror. Another time, he began preening himself in front of a mirror, only to realize that the bearded reflection he was staring at wasn't a mirror image at all, but another, now rather confused man. At times he misinterpreted facial expressions and gestures, sometimes endearingly. Once, when he was lecturing too long, Ms. Edgar, from the wings, repeatedly drew her finger across her throat. He thought she was signalling to him that her chin was bleeding.

Children learn to empathize in large part by recognizing the facial expressions of others. Two areas of the brain, right-hemisphere circuits (which have strong ties to the emotional processors of the brain) and the brain's facial-recognition circuitry, allow us to read people's expressions, and hence their emotions, and even to understand and control our own emotions. We now know that, with various targeted brain exercises, these areas, if compromised, can sometimes be developed with incremental exercise.

I wonder whether face-blindness may well have contributed not only to his shyness, but to the lack of empathy that existed in his earlier life.

Verbatim: Oliver Sacks on face-blindness

Dr. Sacks, for reasons he does not explain in his memoir, remained celibate for over three decades. But when he was 75 years old, he writes, "I met someone I liked. … Timid and inhibited all my life, I let a friendship and intimacy grow between us, perhaps without fully realizing its depth." He and the writer Billy Hayes fell in love. The relationship was in full bloom when Oliver was 77, a redemptive gift of old age. "It has sometimes seemed to me that I have lived at a certain distance from life. This changed when Billy and I fell in love. … [T]he habits of a lifetime's solitude, and a sort of implicit selfishness and self- absorption, had to change."

Another gift of old age was a form of healing with his family. Though Dr. Sacks had many family members in Israel, who fled there after the Second World War (his cousin Abba Eban was Israel's eloquent deputy prime minister in the mid-sixties), he had not visited since he was 22. Oliver had long felt he would be uncomfortable in a deeply religious society. In an interview, he had once described himself as "an old Jewish atheist," a telling phrase, because one would think that being an atheist would disqualify one from identifying with one's original religion. But with Dr. Sacks, truth lay in the particular, the historical and the evolutionary.

In 2014, he finally returned to Israel, to mark the hundredth birthday of a relative. While there, he visited his cousin Robert John Aumann, with whom he had become close in the 1990s. Dr. Aumann was a powerful, athletic man of great warmth and had a huge white beard that made him "look like an ancient sage." A mathematician and rationalist, he had won the Nobel Prize in economics. He was also an Orthodox Jew, and would take his almost 30 children and grandchildren skiing at once, packing kosher plates for them all. He loved to champion the Sabbath's peace, beauty, and what Dr. Dr. Sacks described as its "remoteness from worldy concerns."

"I had felt a little fearful visiting my Orthodox family with my lover, Billy – my mother's words still echoed in my mind – but Billy, too, was warmly received," Dr. Sacks wrote. "How profoundly attitudes had changed, even among the Orthodox, was made clear by Robert John when he invited Billy and me to join him and his family at their opening Sabbath meal."

Dr. Sacks continued: "The peace of the Sabbath, of a stopped world, a time outside time, was palpable, infused everything, and I found myself drenched with a wistfulness, something akin to nostalgia, wondering what if: What if A and B and C had been different? What sort of person might I have been? What sort of life might I have lived?"

Shortly after that, he completed his memoir, On the Move, glad he had been able "for the first time in my life, to make a full and frank declaration of my sexuality, facing the world openly, with no more guilty secrets locked up inside me."

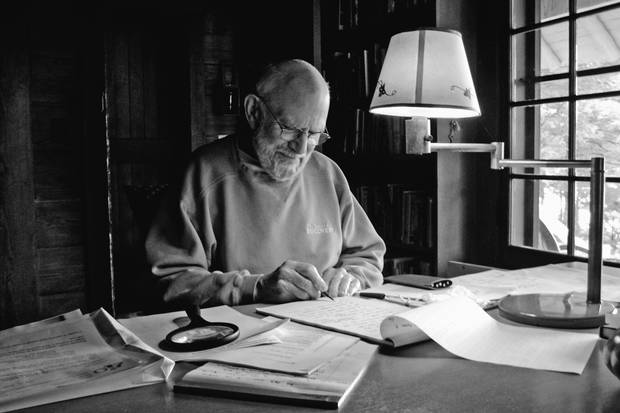

At Blue Mountain Center, 2010.

The art of dying is not learned on the deathbed.

These things, in Oliver Sacks, it seems to me, are all of a piece: his love, since he was a boy, of the close study of particulars in nature; his joyful wonder, and insatiable curiosity; his fascination for the colours orange and indigo, for cephalopods, cycads, metals and chemicals, numbers, ferns, and radishes, invertebrates, all kinds of brains; his ability to see in destitute patients with bizarre, odd, uncanny, problems, their full humanity; his generosity to other, younger authors and scientists; his ability to begin to love late in life, and forgive those he had long loved; and the gratitude, and serenity, that he was able to express, even as he was dying. They are all manifestations of the appreciative sense.

Gratitude is an alloy: part attitude, part feeling. It is a philosophical emotion, the product of taking stock. When someone gives us something and we are appreciative, we are grateful for it, but also for our relationship with them. There is also some humility in being truly grateful. In expressing our thanks, we acknowledge our incompleteness, by expressing our debt to our benefactor.

But to whom or what does the atheist, if he feels thankful for his life as a whole, feel grateful? This is not easy to answer, if one believes that our lives are a product of chance, and molecules in motion.

Somehow, Dr. Sacks seems never to have believed that the random picture that our science, in its current form, paints of the world, need give rise to a disenchanted, nihilistic picture of life as profane.

I was once struck by an incongruity reading his description of a trip to the Arizona desert with the autistic artist Stephen Wiltshire. They had spent an afternoon in the Canyon de Chelly, with a Navajo artist who showed them "a special sacred vantage point" from which to draw.

Both began drawing, while the Navajo artist told Mr. Wiltshire all the myths of that place. But "Stephen was indifferent to all this," wrote Dr. Sacks. Yet when they were done, Mr. Wiltshire's drawing was far better, and "seemed (even to the Navajo artist) to communicate the strange mystery and sacredness of the place. Stephen himself seems almost devoid of any spiritual feeling; nonetheless he had caught … the physical expression of what we, the rest of us, call the 'sacred.' "

Dr. Sacks could have written that Mr. Wiltshire had captured the "beauty," or what was "precious" in the scene, or even its "wondrous," or "mysterious," "awe-inspiring" nature. But he insisted he caught the sacredness of it, a religious category if ever there was one.

This paradox – the depiction of a sacred world, while feeling oneself devoid of spiritual feeling or conviction – may well have applied to Dr. Sacks himself, and indeed may apply to many of us. We want to believe that the planet, life, nature, our loved ones are sacred, but at the same time we do not accept the mystical premises of religions, which are the sources of ideas of the sacred.

Ransack the theories of modern science, and you will find many categories, but the sacred-profane distinction will not be among them. The universe, we are told, is composed of matter in purposeless motion, governed in large part by chance. The idea that life has a design, and organisms a teleology, or end, became suspect, of course, with Dr. Sacks's hero, Charles Darwin. Evolution is opportunistic, and emerges from a series of chemical accidents producing random mutations; it is not toward some end, as was believed by Aristotle, pre-Darwinian science, and of course many religions.

Yet many of us live with the two, with the scientific and the sacred, both at once. And perhaps one of the reasons Dr. Sacks's work has such a strong appeal is that, despite his being a champion of modern science, he approached his patients' lives, life and nature with a reverence that treats them as almost sacred, and this appeals particularly to those of a modern, secular cast of mind.

It appeals, precisely because the premise that we are nothing but molecules in random motion so disenchants the universe for us, and leaves us feeling longing for more. It is a disenchantment that is hard for even the hardheaded scientist to tolerate; we prefer our nihilism without too deep an abyss. It is not enough to wonder about the mystery; we make it sacred, too.

And we long for thinkers like Dr. Sacks, who remind us that science is about wonder, and who, by so doing, hint that perhaps the idea that we are merely matter in motion is just part of the story, but not the whole story. His emphasis on wonder reminds us that science is about opening, not just closing, questions.

Why is gratitude of such great magnitude so rare?

Perhaps because gratitude does not always go unopposed. Psychoanalysts have often seen gratitude as having an emotional opposite, envy. Sometimes a flash of envy can be a helpful sign, a spur that tells you, "You know, you really want this – try for it." But very often, the envious person sees something wonderful in the world, and instead of appreciating it, attempts to make the envious feeling go away, by devaluing or denying its worth (those grapes were sour, anyway); or he or she may try to spoil or destroy the envied object in reality. If one does this enough, one ends up feeling starved, because one finds oneself living in an emptied world. Envy destroys the possibility of love; confronted by a cherished, idealized object of our affection, envy cannot tolerate the goodness in them, and seeks to destroy them; and envy does so by first undermining any feelings of gratefulness we might have for that person.

The envious have a particularly hard time growing old and dying.

They cannot tolerate the fact that the young, and not they, have their lives before them. They feel pain, and emptiness. We speak of people being consumed with envy – but filled with gratitude. It's paradoxical that, by acknowledging that there are wonderful things in the world, and that we are incomplete, we can feel filled up – even as we bid the world farewell.

Ms. Edgar told me that her atheist friend sometimes liked to be read, of all things, the Bible. When I think of Oliver's last days, I think of a biblical sentence that I've always found instructive in the twofold art of living and dying.

It reads, "And Abraham died … full of years."

Not emptied of them; filled by them.

Norman Doidge, MD, is is the author of The Brain That Changes Itself and of the just-released expanded paperback edition of The Brain's Way of Healing.