It's now modern – at least for those of us in the overindulged West – to profess a preference for experiences over things. Experiences are widely acknowledged to last a lifetime, while our tendency to acquire is a sort of dirty habit we are supposed to overcome with some restraint, like smoking or eating carbs.

Whether this distaste with the material world has anything to do with the rise of the virtual or digital one, a severe, almost repentant minimalism is so in among millennials that the chronicles of those who have vowed to live with less seem more of-the-moment than shopping guides.

Beyond whatever pleasures there might be in self-denial (if anyone knows, please do share), this kind of thinking misses the point entirely. As those of us who have survived the final disassembly of their parents' home can fully appreciate, there is a deep-rooted connection between the things acquired over a lifetime, and human experience. So much so that as we clear the contents of the bedroom or the living room of someone who was central to our lives and is now gone, almost every single thing they have left behind seems to radiate with meaning and memories.

But beyond the grave and final reckoning of our things and our selves, aren't the triggers to our memories almost always objects? Whether it's a story of acquisition or discovery, or a sense memory like Proust's madeleine, our things are like 3-D printouts of our stories. And it is so often the thing above even the thought or idea that starts the reverie of recollection.

Consider the T-shirt you stole from your high-school boyfriend that's still in the back of your top dresser drawer. The box of mints with the green-and-white striped label that were your grandmother's favourite. The hand-woven bag you got that time in Mexico, or the worn carpet in the family room that you bought because it always reminds you of your favourite children's book with its funny animal parade.

Hence nostalgia. The voyeuristic draw of the vitrine, or cabinet of curiosity. The haunting immediacy of a photo collection, or the emotional pull of the keepsake or memento. Even the notion, from the 12th century French for "to remember, or come to mind," of the souvenir. Each of us, it turns out, has a lifelong sideline in the museum business as curators of our own little dioramas of our tastes and aspirations – and, yes, experiences. By collecting, preserving and displaying our precious things we defy our mortality by attempting to live on in memory.

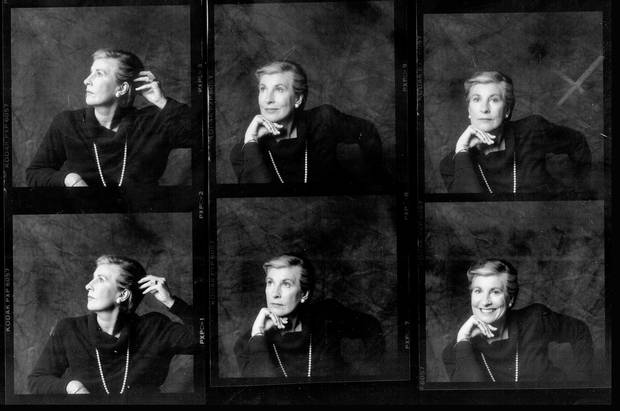

How and why the things that we acquire and surround ourselves with have become the containers of our stories, if not actual expressions of ourselves is something I have attempted to explore in a new memoir about my late mother called What Remains: Object Lessons of Love and Loss. Each chapter centres on a different thing or object that reminds me of her. Each of these items, which range from silver satin sofas to a pack of Craven "A" cigarettes, I use as a starting point, lens and metaphor to talk about who she was. The first line of the book is that the last word my mother ever said to me was "pearls."

While this might be a novel approach to memoir, I am hardly a pioneer in looking at material culture in this way. The idea that our possessions have totemic powers is an ancient one. Early peoples treated their things as meaningful in ritual and rite – some so precious that they planned to take them along in the afterworld by being buried with them. What is the science of anthropology if not an acknowledgment of the importance of objects in human culture? The archeological dig – an exercise in unearthing memory through possessions – is a search for clues as to how lost cultures lived and what they cared about through what they had and kept and used.

Not only is it very old, its also basic. After "Mommy" or "Daddy", or something random and domestic like "cat" or "apple," one of the very first words a young child learns to say aloud is "mine." And of course they are often inclined to say it with ferocity, as if their very being was at stake. To "have," at least according to Jean-Paul Sartre, is as essential as the verb, "to be."

Our things may not literally be us, but they do offer both insight and reflection into what makes each one of us tick. Like it or not, we read every book by its cover, and judge everyone we meet by their shoes. Which is why we live our lives engaged in a deep and meaningful relationship with both our possessions, and also those of whom we love. This isn't a sad result of "consumer society". It is merely human.

Karen von Hahn's book What Remains is published by House of Anansi Press.