The Canadian Cook Book, published in 1923.Julie Van Rosendaal

My mom likes to tell a story of three-year-old me, who asked when I could start cooking for myself. “When you can read a recipe by yourself,” she told me, “then you can cook for yourself.” And so I went off with a stack of cookbooks and began to learn how to read.

I kept reading cookbooks through my childhood and teenage years. I read them in bed (still do) and checked them out of the library. I flipped through people’s collections whenever I found myself babysitting or in my friends’ kitchens. I was interested in cooking, yes, but these books provide more than just instruction; they’re aspirational anthologies of our day-to-day lives, connecting us to our past and helping us imagine how we might comfort, nurture and socialize with one another in the future. Older texts have as much to do with history as cookery, documenting the challenges and solutions of daily home life.

Around Canada Day, there’s often discussion about what constitutes our national cuisine; looking back through old cookbooks allows a peek into the way we have lived and fed one another over the centuries. My vintage collection is substantial – the shelves are packed two deep with books inherited from relatives, gifted from friends and unearthed at garage sales. I’m drawn to their musty smells, falling-out pages and notes in the margins. The oldest ones are my favourites, predating the arrival of exciting convenience foods that inspired curious combinations such as frankfurters and Jell-O.

I wondered which books were the most authentic representations of pre-20th-century Canadian home life, so I spent an afternoon flipping through Liz Driver’s massive 1,257 page tome, Culinary Landmarks, a bibliography of Canadian cookbooks, in the local history room of our downtown library. (You can also find it on Google Books.)

“Food is at the very heart of living,” Driver, the director and curator of Toronto’s Campbell House Museum, later told me, confirming my feelings that cookbooks are about more than just recipes. Her bibliography contains entries for 2,276 titles – every cookbook of 16 pages or more published within the borders of present-day Canada from 1825 to 1949. But beyond that, it celebrates cookbooks (whether locally written or a Canadian edition of a foreign work) and their authors as a significant part of Canada’s literary history and documents political, economic, social, agricultural and immigration trends through the lens of our home kitchens.

Of course, not all cookbooks published in Canada originated here. Many are Canadian versions of books originally released in Britain or the United States, larger markets that even back then were tough to compete with in the publishing world. The Canadian Receipt Book, for example, was published 150 years ago to celebrate the new Dominion of Canada. It reflects late 19th-century home life with instructions not only for cooking and food preservation, but home remedies for measles and leprosy in pigs. An original copy was discovered last year and republished by Rock’s Mills Press with the help of special collections librarian and cookbook expert Melissa McAfee.

McAfee points to Maria Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery, a popular British cookbook originally published in 1806, as the likely original source of the book’s text. At the time, she says, it wasn’t uncommon for 19th-century Canadian cookbook texts to be lifted from British or American sources. Similarly, the Canadian edition of the Boston Cooking School Cookbook – the first book to use cups as standard measurements – was published in 1904, and became as influential here as it was in the United States. Reinforced by waves of immigration, reprints of British and American cookbooks became the provenance for culinary techniques and traditions in Canada.

There were few written records of the food preparation of precolonial Canada, with Indigenous communities passing on customs and techniques in the oral tradition. The release of La Cuisinière Bourgeoise, an edition of a text from France published in Quebec City, officially marked the beginning of Canadian cookbook publishing in 1825. Soon after, La Cuisinière Canadienne became the first French language cookbook written in Canada. Its anonymous compiler(s) helped to identify French-Canadian cooking as a distinct cuisine and put into action “the ideals of a political movement that aimed to preserve French culture in the British colony,” Driver writes in Culinary Landmarks.

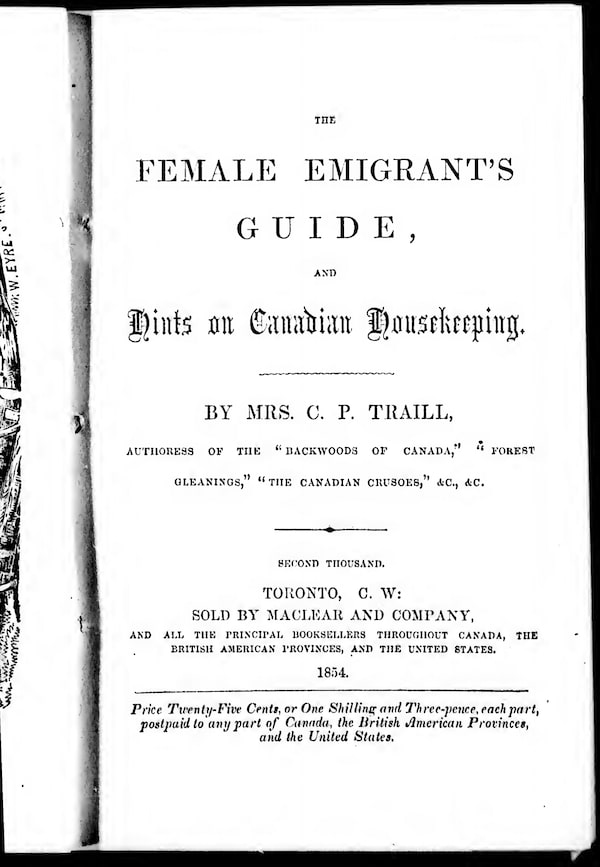

The Female Emigrant’s Guide of 1854.

Before 1950, Canadian publishing remained focused on Ontario, with 1,240 culinary titles published in the province – almost four times as many as in Quebec. The Female Emigrant’s Guide of 1854 by Catharine Parr Traill, who lived near Peterborough in what was then known as Canada West, offers advice about seasonal food sourcing and preparation for immigrants to Victorian-era Canada. She starts with what to pack for the voyage and moves on to topics such as raising bees, leavening bread with hops, building roasters and making venison stew and dandelion coffee. (The book was republished in 2017 by McGill-Queen’s University Press.) Household Recipes of Domestic Cookery was a general-subject cookbook by Montrealer Constance Hart. Traill and Hart were, notes Driver, the only positively identified women up to 1877 who were writing in English specifically for Canadian kitchens.

It’s also notable that most pre-1950 Canadian cookbooks were compiled outside the conventional publishing realm – by food companies, manufacturers of kitchen equipment and community, church and charitable groups. Community cookbooks provide a uniquely accurate record of Canadian life because they reflect the tastes and cooking practices of the home cooks who contribute the recipes. Driver cites The Home Cook Book, an 1877 compilation of recipes authored by “the Ladies of Toronto and Chief Cities and Towns in Canada,” as marking the beginning of “a grassroots publishing phenomenon that would help to shape Canadian cooking for the next hundred years or more.”

With recipes gathered from (and attributed to) home cooks, these self-published collections can be rare; because of their small print runs and formats, they aren’t preserved in libraries and tend to have shorter lifespans because of their exposure to kitchen elements (food, water and fire), but they offer a more authentic record of what people ate, drank and prepared at home. (Most existing copies are preserved in libraries’ special collections.)

In 1900, cookery became a legitimate subject of study, triggering the reorganization of recipes into a standardized layout, with a list of measured ingredients followed by step-by-step instructions – the format we recognize today. Books published before that point (and still some released after), are notable for the brevity of their recipes; they were often no more than a descriptive sentence or two and credited to a housewife by way of her husband (Dainty Salad, Mrs. James Warnock). Before the arrival of gas ranges and standardized measures, kitchen equipment was still largely unreliable. And recipe contributors presumed the reader had basic cooking knowledge.

Promotional cookbooks were also common in the early 20th century as technology introduced new kitchen gadgets and ingredients. These books tended to be small and more affordable. Because wheat was (and is) such a significant Canadian crop, many milling companies printed their own books. Perhaps the best known is the Five Roses Cookbook, first published in 1913 by the Lake of the Woods Milling Company. Not only were the recipes from local homemakers, but the book was printed in Canada on paper produced in a Canadian mill. By 1915, almost a million copies were in daily use – practically one copy for every second Canadian home.

I’m one of the now many millions of Canadians who owns this book, although mine is a reprint of the 1967 version released in 2011, which doesn’t have quite the same charm. It remains a solid resource, whether you’re looking for a basic pancake formula or classic butter tart recipe, and provides proof that technology really has had little effect on the process of making a perfect biscuit.

Recipes in the Canadian Cook Book from 1923.Julie Van Rosendaal

On the traditional publishing side, the Canadian Cook Book, published in 1923 and commonly known as the “Blue Cookbook” until a redesign ditched its blue cover in 1948, became the first mass-produced Canadian cookbook. It was written by Nellie Lyle Pattinson, who was the director of domestic science at Toronto’s Central Technical School and its popularity revived the floundering Ryerson Press. “At the time, the book came out there really was no textbook for girls in home economics classes,” Driver told me. “It caught on across the country.”

She points out that the evolution of revised editions by newer authors Helen Wattie and Elinor Donaldson is a good example of how cookbooks map cultural changes. The 1953 edition is notable for acknowledging regional cooking and immigration patterns across the country and contains the first recipe she has seen in a Canadian publication for homemade pizza, reflective of an increased postwar Italian population. She cites subtle shifts that signal transitions away from the roots of recipes, adapting them to new cultures and surroundings. “There’s an asterisk beside oregano that says, ‘if you can’t find this, or don’t recognize it, you can use sage,’ ” she says. “These books were crucial for creating food habits.”

It’s the 1963 version (and the 28th printing) of the Canadian Cook Book my mom has on her shelf. She’s stuffed it full of her handwritten notes and has taped a handful of favourite recipes from other sources onto the empty pages, included by the publisher for that purpose, at the back. Among them are my grandma’s butter tart recipe and the formulas for her baked corned beef and pecan dip. (The latter is far more delicious than it sounds.) My own copy, discovered for $4 at a fundraising book sale, contains a Post-It noting that the book was used for high-school home ec classes in Saskatchewan in 1963.

Whether or not we still need cookbooks in the age of Google is hotly debated and I’m not sure any volumes in my current collection will ever be used in the same way as handbooks of kitchens past. But the publishing machine doesn’t show signs of slowing down – old or new, the nostalgia of these collections we can hold in our hands will always bring us back to a certain time and place.

Five Roses Butter Tarts

The first printed recipe for butter tarts, described merely as “filling for tarts,” appeared in a cookbook produced by the Royal Victoria Hospital’s Woman’s Auxiliary in Barrie, Ont., in 1900, attributed to Mrs. Malcolm (Mary) MacLeod. The Five Roses Cookbook version is perhaps the most used in Canadian cookbook history – and, notably, contains walnuts, currants and raisins.

Pastry

- 2 1/2 cup Five Roses® all-purpose flour

- 1 tsp salt

- 1 cup butter, cold

- 1/2 cup water, cold

Filling

- 2 eggs

- 1 cup brown sugar

- 1/2 tsp salt

- 1 Tbsp cider vinegar

- 1/2 cup maple syrup

- 1/3 cup butter, melted

- 3/4 cup walnuts, chopped

- 1/2 cup currants

- 1/2 cup raisins

To make the pastry, combine the dry ingredients in a large mixing bowl. Add the butter and rub into the flour until mixture resembles coarse meal. Drizzle in enough water until the dough begins to hold together. Turn the dough out onto a floured surface and shape into a disc (do not overwork the dough). Wrap in plastic wrap and refrigerate for 30 minutes.

Roll out dough to 1/8-inch thickness. Cut out 3-inch rounds and line 12 muffin cups with dough. Chill.

Whisk together eggs and brown sugar. Add the salt, vinegar, maple syrup and melted butter; combine well. In small bowl mix together walnuts, currants and raisins.

Divide the walnut-fruit mixture between the tart shells. Fill each tart with approximately 1/4 cup filling. Bake in a preheated 350ºF (180ºC) oven for 20-25 minutes or until set.