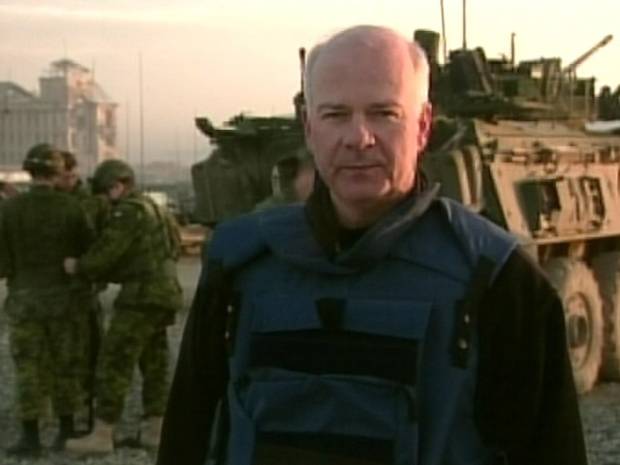

Peter Mansbridge sits down with The Globe at the Avenue Road Diner on June 17, 2002.

LOUIE PALU/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

For decades, CBC's Peter Mansbridge has been Canada's voice on air as the host of The National. This week, he confirmed that Canada Day 2017 will be his last day with the program.

In 2002, The Globe's Sarah Hampson took a detailed look at Mr. Mansbridge's career as a journalist, his process and his thoughts on how the emergence of digital media was changing the TV business. Here is her profile from June 22, 2002.

The next time you watch Peter Mansbridge sitting behind his anchorman desk in his pressed suit and perfect tie reading the news in that pressed and perfect fashion of his, think of him holed up in his cottage in Quebec's Gatineau Hills, all rumpled and intense, one hand running through his thinning hair, as he writes a fictional television drama. Maybe he's drinking a beer, gazing out the window, lost in thought, tieless, imagine, sockless even.

It gives me pleasure to report that Peter Mansbridge is not as boring as his teleprompter scripts. He is not the man you see on CBC's The National. At least, that's what he ever so politely would like to point out.

Polite, Mansbridge is. Always. He answers questions to address whatever misconceptions the public may have of him in a most calm manner, in an official tone, come to think of it, just like he would tell us there are floods in Manitoba and terrorist bombs in the Middle East. "I'm a pretty funny guy, actually," he says, when asked if he has a sense of humour. His mouth curves into an impish, almost embarrassed smile.

Well, all I can say is that the revelation that there is lots going on beneath his familiar and emotionless television exterior helps explain why he seems to be such a babe magnet, or, more accurately, a wife magnet. In 1998, he married Cynthia Dale, an actress 12 years his junior. It is his third marriage. They have a son, William, aged 3. Before that, he was married to fellow CBC journalist Wendy Mesley, a woman who radiates just the right amount of vulnerability and intelligence to weaken the knees of every grown man I know. His first marriage, at a young age, to a woman (name undisclosed) from his pre-anchor days, produced two daughters, now adults living in Western Canada.

So I always wondered what his appeal is, aside from the fact that he's probably one of Canada's best-known celebrities and that, arguably, a man who has the required authority and calm to tell the nation that the world has survived another day is not a bad sort to have in your bed at night.

Not that I was expecting to find out who the man beneath the TV makeup is. The interview is about the business of news in the fragmented media marketplace; the endurance of network newscasts despite observers' predictions that they'll go the way of the dinosaurs in view of the customer-is-king ethos of the 500-channel Internet-friendly information-delivery systems; and, last but not least, how The National got its groove back. While CTV's Lloyd Robertson beats the Mansbridge-led newscast on most nights, The National has more viewers this year than it did last year, according to CBC spokesman Ruth-Ellen Soles.

Besides, Mansbridge is notoriously close-lipped about his private life. Most private information he does give is careful and clipped. Asked about his son, he says curtly that "he is great fun." Then, perhaps to be helpful, and after a moment's pause, he offers a sweet, benign story about taking him to a Stanley Cup playoff game with the Toronto Maple Leafs. When friends later told him they were seen on television, Mansbridge got a copy of the tape, isolated the bits in which he and his son appeared and showed it to him. "He was thrilled, but the next week, when we were watching another playoff game, he looked at the television and asked, 'Where are we, Dad?'"

Somehow though, despite his desire to stick to the headlines of his life and work, we get on to the subject of what he might do after he leaves the airwaves. "I don't want to do it forever," he says about his job, adding the caveat that, "of course, when forever comes, I may say, 'Forever hasn't arrived yet.'"

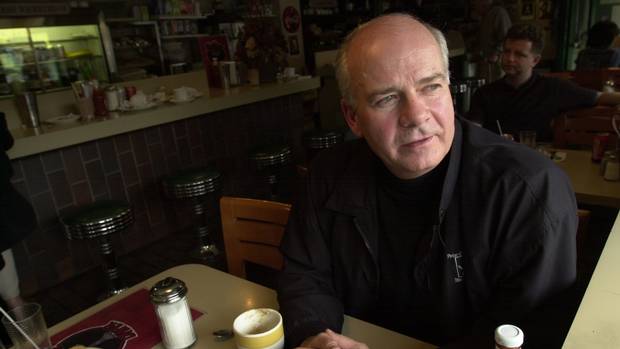

Peter Mansbridge with the puppets of Sesame Park, the Canadianized version of Sesame Street, in 1996.

HANDOUT/THE CANADIAN PRESS

He will be 54 this year. "I've worked nights for the past 25 years," he says. Might he consider writing a book, I wonder. Isn't it a way for an anchor to prove that he thinks, to prove that he can do more than just read the news that's been scripted for him? Mansbridge looks a little hurt at this suggestion.

"It would bother me if people felt that Mansbridge, [Lloyd] Robertson or [Tom] Brokaw [of NBC's Nightly News] really only knew how to sit there and read the news," he says, pointing out that on "big-issue" nights such as an election or, say, the terrorist events of Sept. 11, "if [a journalist] is out of his depth, viewers know it instantly." (Of Mansbridge's handling of Sept. 11, National Post television critic Scott Feschuk wrote that he was "a marvel on the fly.") He would write a book, he says, if he could do more than "tell war stories about myself." He admires Brokaw's book, The Greatest Generation, about the men and women who came of age in the Depression and Second World War, for instance. "That's a real contribution," he says.

Then he recalls the flight home last summer from England, when he read a screenplay that had been sent to his wife for consideration. "It was a TV drama, locally produced. And I thought, 'What a joke. Somebody wrote this and they're getting paid for it.' On that flight, I came up with a basic idea and then spent a week in the Gatineau writing an outline. The luxury of dealing with fiction and not fact is a wonderful thing." He sold the outline – to whom, he can't say – and "if it makes it to the next level, it will be made."

Would he like to write more? "It was a personal challenge," he continues. "I made a judgment that it was crap so I thought, 'Well, do better.' But I've got other ideas. It's a matter of having the time."

On a busy weekday lunchtime, we meet at the Avenue Road Diner in midtown Toronto. It's the everyday man-of-the-neighbourhood Mansbridge who walks in the door in his black trousers, black turtleneck and jacket. The place is very CBC townhallish. There are those small round stools pulled up to the Formica countertop bar. There's Joyce, the waitress who knows how "Peter" takes his all-day breakfast. Everything about the place is decent and non-corporate – CBC over easy.

Quickly, though, Mansbridge confounds expectations. "We lost our way," he admits of the CBC news in the early nineties, the decade when concern about fragmentation heightened. The death of Barbara Frum, who was the face and mind of the network's newscast, also caused a rethink. "We lost a lot of viewers who depended on a certain kind of programming that they didn't see any more… . We were doing [gossipy tabloid journalism] and … we'd then have a panel discussion about the relevance of all this… . It's really hard to excuse yourself when you're the public broadcaster."

That period, about five years after he took over from Knowlton Nash in 1987, was the only time he questioned his decision to stay with the network, he says. Mansbridge had been offered the anchor's chair to keep him after CBS approached him to move to the United States.

What The National looked like in 1988

What The National should do, and has returned to doing with success, is "try to answer the larger questions," Mansbridge explains. Sept. 11 proved that. Many people may have started by turning to CNN but, "at a certain point in that day, people started looking for more than the emotion and the horror of the moment… . They wanted an understanding of the why, and by the prime-time hours, not only were we ahead of CNN, but we were ahead of everyone put together… . I was on the air for 16 hours straight and at any one time I was turning to help from [CBC correspondents] a David Halton, a Patrick Brown, Don Murray, Don Newman, a Céline Galipeau, names that didn't just arrive on the scene but that have their credentials.

"We were well positioned. In the months previous, we'd been to Afghanistan looking at the Taliban, updating our material on al-Qaeda. We'd done a full-length documentary on bin Laden. The other [networks] weren't able to do this because they don't have the resources. These demands are not upon them. They are upon us. We place them on ourselves."

C-span, a U.S-based public-affairs station, and other satellite news channels, ran The National for almost a month every night following the terrorist attacks, Mansbridge says. Trail of a Terrorist, a documentary by Terence McKenna, was sold to the PBS show Frontline and several European countries.

Was he responsible for helping The National find its way again? "Yes, but I wouldn't take credit for all of it," he says. "I'm seen as the front person but I'm just one of a group of senior editors." This may be part of the standard public-broadcasting mantra – the "we do it for the good of the world" argument and not for the money or the glory – but Mansbridge is completely guileless when he explains that "I have lots of reason to be careful about how I see myself. I have pretty humble roots."

When he was 19 and a high-school dropout, he was working for a small airline in northern Manitoba. "Some guy by fluke heard my voice announcing an airline's departure." The man was the manager of CBC Radio's northern service in Churchill. "I started the next night," Mansbridge says.

His first gig as the station's disc jockey didn't work out because, "I'm terrible at music and have no sense of tone or how to pick a winning song." One night, the song Bridge over Troubled Water came into the station. "I listened to it, and said, 'This is five minutes long. It's never going to make it.' " Shortly after, Mansbridge pitched the idea of a newscast for the station. For the next 20 years, he worked as a reporter, first for radio and later for TV, always with CBC.

Peter Mansbridge from his pre-National days

1:06

He has never lost his love of reporting, which he still does. "I work the phones every day," he says. And he never takes his work or its significance lightly. "In television, you have one shot to communicate difficult subjects. People aren't sitting there with their VCRs, saying, 'I didn't understand that. Let me rewind.'"

The Internet may be a resource that explains more complex issues, but "let's not fool ourselves. Most people get news from TV, and that's always bothered me," Mansbridge says. "Sometimes their only source is TV. I know what they're getting. They're not getting enough. We [at the CBC] like to think we take it beyond the headlines because we do documentaries, we go for an hour, we do analysis. But if you take [the script of] an hour-long newscast … you couldn't fill the front page of your paper."

See? Readjust your television perception, folks. Mansbridge is our very own thinking head.

A message from @petermansbridge. pic.twitter.com/4XFYizJUBx

— The National (@CBCTheNational) September 6, 2016