This is part of Life After Privacy, a four-part series on the risks, challenges and opportunities for citizens and consumers posed by a world where your private information is widely available to governments and corporations.

Personal information was once stored in just two places: your home or your head. Today, that same information is worth billions to advertisers and data brokers, operating quietly in nearly every facet of your life.

Canadians trade their data every day for convenient products or perks. But have you ever wondered what happens to your data once you hand it over? Or how you might profit instead?

Below, explore the complicated relationship between you and Big Data: from how your information's collected, to where it's used, to how you can profit instead.

The simple act of browsing the Internet or subscribing to magazines will push your personal information into a complex industry of buyers, sellers and brokers.

The Internet

The Internet

Social Networks

Social Networks

Mobile Phones

Mobile Phones

Loyalty Cards

Loyalty Cards

The Internet

Monitoring begins with the cookie, a small text file advertisers save on your computer. It’s retrieved later and compiled with other cookies to develop a complex portrait of your online behaviour.

The scale of online tracking can be staggering. See how many cookies are tracking your activity here.

Social Networks

You can download your Facebook data to see how much information is on record, including a history of every advertisement you've clicked.

Mobile Phones

Telecommunications giant Rogers Communications announced an advertising program last year to send four promotions per week to its mobile customers via text message. The idea is simple: opt in and get $1 off a pizza slice when you’re near a Pizza Hut at lunch time.

The scale of this tracking becomes clear in this map, plotting millions of tweets around the world based on geo-location.

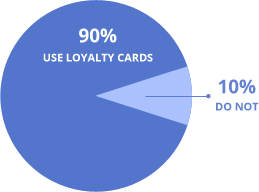

Loyalty Cards

But for businesses, the real value lies in mining that information for insights into customer behaviour. Businesses can track your movements and buying habits, helping them determine whether you’re a vegetarian or predict when you’re about to have a baby.

Data flows from social networks and Internet companies to data brokers.

They combine this with other data to create valuable lists — curated data on specific groups with names like “Canadians with Discretionary Funds” and “Tropical Beach Resort Goers.” These lists are bought, sold, exchanged and bartered, forming the basis of the Big Data economy.

Canadians can still be wrapped up in the Big Data economy without using mobile phones or loyalty cards.

One of the largest data brokers, Axciom Communications, uses more than 500 Canadian phone directories to create a profile about you by pairing your name, phone number and address with census information such as income and housing. In the United States, they're known for trying to collect 1,500 data points on every American, making use of everything from court records to birth records to magazine subscriptions.

The destination of all the collecting, analyzing and trading are the data users. These are mostly marketers and advertisers, but can include fundraisers or non-profits. They buy or rent lists to better understand their target demographic based on specific traits such as ethnicity, income, property value, and hobbies.

Data users don’t target you specifically. Instead, they’ll analyze a specific list to build profiles. Marketers can blanket a target area with advertising or open a new store in an up-and-coming neighbourhood — expensive decisions made all the more easy by using data.

Datacoup is a New York startup that pays to access your data, including your social networks and credit card statements. Currently in beta testing, the company will eventually sell intel on its users to marketing companies (after removing any personally identifying information).

Matt Hogan, the company’s CEO and founder, says collections of personal information are like valuable diamonds created every day through purchases and Internet use.

“Data brokers are finding all these diamonds and reaping all the benefits,” he says.

Even if you don’t want to sell your data, some are advocating a system where each Canadian maintains one official file of data in the cloud, dubbed the “golden record.”

Ontario’s Information and Privacy Commissioner Ann Cavoukian said this system would let Canadians store everything from phone numbers to health records to tax information, controlling who has access and how it’s used. Personal data vaults, such as the one offered by Personal.com, already offer this service. In the future, data vaults could include features to open your data to companies — for a price.

Graphics by Murat Yukselir

Sources: The Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic