An atomic bomb detonated above Hiroshima on a summer morning in 1945. Dropped by the United States, Little Boy – a perversely cute name given to a devilish weapon – killed 140,000 people, more than half of whom died instantly in the blast. The city was reduced to a flat expanse of rubble, its many wooden buildings set on fire.

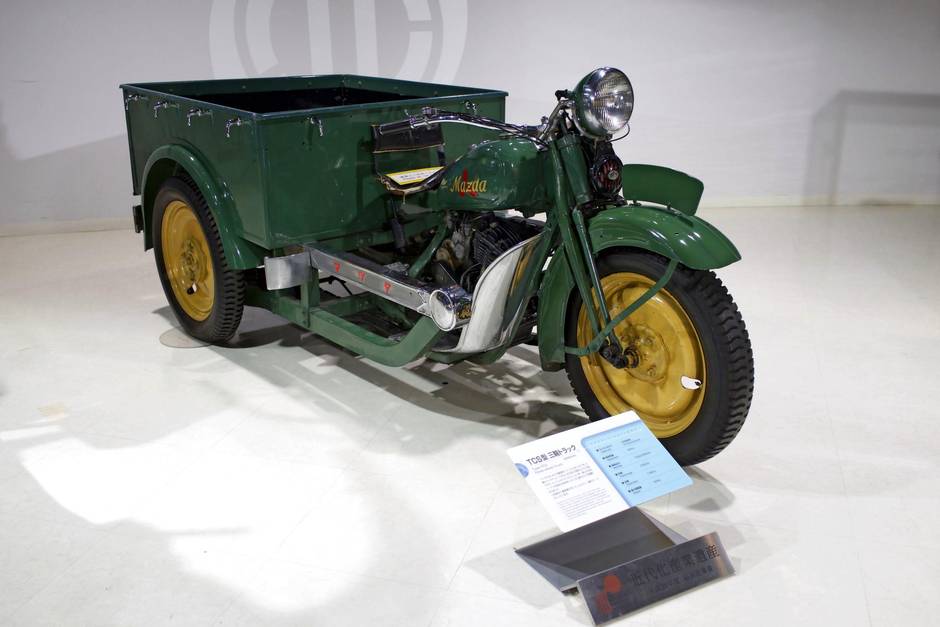

Hiroshima is home to Mazda, a company known back then as a maker of three-wheeled motorbikes. Before that, as Toyo Cork Kogyo, it made corks.

Just four years after the bomb fell, Mazda’s factory was up and running again, making more three-wheeled motorbikes. The company supported reconstruction of the city, and its citizens were forever grateful.

This is a story the people at Mazda tell about their company. It’s a story presented in slide show form by Mazda’s chief of global public relations, in a conference room at head office in Hiroshima. It’s a story about resilience, perseverance and – here’s where it gets weird – a story meant to show why Mazda was the only company able to put rotary engines into mass production. Huh?

Today, the dream of rotary is dead. Conventional wisdom is that these engines can’t be made to meet emissions regulations. But why, then, would Mazda show off the new RX-Vision rotary sports car concept at the Tokyo Motor Show? Why would Mazda give us this story about resilience and perseverance? And why would it bring a bunch of old rotary cars out of its archive for us to whip around their test track? Is the rotary engine really dead?

At a secret location deep in the Japanese countryside, amid steep hills and deep valleys and quaint villages, far away from prying spy photographers, is Mazda’s Mine Proving Grounds. Visitors are not allowed to transmit photos, lest the transmission give away its location. An odd rule, given the fact it was a public track until recently – but never mind. There are cars to drive.

A tantalizing row of mint-condition old rotary-powered machines waits in the pit lane.

Long before the Miata/MX-5 and the “zoom-zoom” slogan, Mazda had the RX-7. Through three generations, it represented affordable performance; a Japanese sports car to compete with the best from Europe and America. The RX-7 is on the cusp of becoming a classic – if, that is, you can find one that hasn’t been given the full Fast and Furious treatment.

Ask any rotorhead – those gluttons for punishment, those few proud devotees of the rotary engine – the best way to understand what’s so special about these cars, and they’ll say: drive one.

So, what’s so special?

Rudimentary research on the RX8club message boards reveals the benefits: high power output relative to the size and weight of engine, and a smooth high-revving nature – according to a user who goes by the handle Brettus. A second source, Pistonhater, agreed. EricB added, “Im [sic] a blind rotorhead.”

Will I too become a blind rotorhead after driving an RX-7?

It’s cold out, and the tires on this 1978 RX-7 look period correct. Too correct, actually. Turns out it’s still on the original rubber. Someone has already spun the car once today. Best tread carefully.

The seats are flat and low, and the steering wheel is large and thin. The first RX-7 is slow by modern standards, but Brettus was correct, even this 37-year-old example feels happiest when spun up near its 7,000 rpm redline. It’s smooth and linear, with a sound like a prolonged cow fart, and silly-fun to drive – until suddenly a piercing alarm goes off in the cabin. Is this the last sound you hear before a rotary blows up? Apparently no, just an alarm that goes off when you hit the redline. The car is so comfortable at high revs, the alarm is a necessity.

The second-generation RX-7 is a special 10th anniversary edition model from 1988. It has matching white-on-white wheels and paint. It looks like a Porsche 944, except cleaner, smaller. A purposeful-looking wedge. The second RX-7 – FC to rotorheads – feels more like a sports car. It rolls into turns but then settles into a reassuring neutral state, a benefit of balance granted by a small rotary engine pushed far back towards the cabin. It’s both comfortable and fiendish, a car you could happily imagine driving on perfect summer days and neglecting, maintenance-wise.

The final RX-7 – the third generation, known as FD – is a different beast altogether. It’s a demon compared to the other two. Under the hood is a twin-rotor engine boosted by a sequential twin-turbo setup. It was a product of the 1990s, as was the Honda NSX, twin-turbo Nissan 300ZX, A80 Toyota Supra and Subaru Impreza 22B. Collectively, they represent the high-water mark for Japanese sports cars.

Just as you think the FD is running out of boost around 4,000 rpm, the second turbo kicks in and delivers the full 276 horsepower. The test car is on barely cut slicks, providing neck-straining grip. The chassis stays flat through corners.

The cabin, though, is uncomfortably cramped, like sitting inside a small shoe. Your sense of speed is heightened because you sit so low. The FD is worthy of all the fast-car cliches usually thrown at it.

One lap in each model isn’t enough to get the full picture, but any car that’s both affordable and exciting to drive is worthy of high praise, and all Mazda’s RX-7s tick both boxes. But they’re more than that – they’re weird. And car people tend to latch onto anything weird: cars with impractical motor placement, quirky design, unfortunate names and unusual engines.

Weirdness imbues cars with an added (imagined?) sense of character and specialness. The RX-7s are as lovable for their performance as they are for the fact they really have no business existing.

In the 1950s, the rotary was a “dream engine,” a device envisioned by Felix Wankel working for NSU in West Germany. Many auto makers tried and failed to mass produce it, including Ford, GM, Rolls-Royce, Porsche and Alfa Romeo. Mazda’s first rotary car came out around the same time as transistor radios and jet engines became ubiquitous. It must have felt like a new beginning.

But, in 2012, Mazda stopped production of its last rotary car and, ever since, rotorheads have been dreaming of a successor.

Mazda’s factory and headquarters in Hiroshima is like a city unto itself. But there is no expensive high-rise in which to house top executives and burnish the brand to the world. There are only endless rows of anonymous low-rise buildings. In the lunch room, a pair of faded wood-rimmed floral couches, the latest in 1980s office decor. The hallways are wide and empty, with grey floors. There’s a poster in one factory building that says, “I [Heart] Work.” The company’s official museum is just a dimly lit floor off the factory; the gift shop a lone rack of branded memorabilia.

Mazda is not prone to frivolous spending, it would seem.

“We’ve had some bad times at Mazda and we want to make sure they never happen again,” said Akira Marumoto, the company’s executive vice-president.

During the financial meltdown in 2008, Ford sold its stake in Mazda. Between the loss of that partnership and recession, Mazda was in bad shape. The company lost money from 2009-2012. It’s only in the last two years that it has returned to profitability.

Both Marumoto and CEO Masamichi Kogai seem like patient businessmen. They’re working to fix the business behind the scenes, setting the company on a solid foundation for its future as a small, independent auto maker.

“We need to make sure the business is good, which is why I have to say the RX-Vision is just a dream for now – but one day we hope to make our dream come true,” Marumoto said.

At the Tokyo show, Mazda claimed to have made a breakthrough with rotary engine technology, but none of the executives would talk about what exactly that might be. All we know is that a core group of engineers at Mazda have been continuously working on rotary engine development.

If they can solve the fuel consumption and emissions issues – and Mazda can make a business case for a new rotary sports car – we’ll likely see a more production-ready concept at the 2017 Tokyo Motor Show. It would be the 50th anniversary of Mazda’s first rotary-powered car. A production model would then be ready by 2020, the company’s 100th anniversary. Works out nicely, doesn’t it?

But the real question remains, as much as rotorheads want to drive a new rotary-powered sports car, could it ever be a sound business move? While other companies pour money into hybrids and electric vehicles and hydrogen, Mazda forges ahead alone with the rotary. Resilience and perseverance are admirable qualities if you’re working to build something great, less so if you’re working on something obsolete. Which is the case for the rotary? We’ll know in a couple years.

The writer was a guest of the auto maker. Content was not subject to approval.

Like us on Facebook

Add us to your circles

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.