The best advice for Canadian investors over the past few years has been to stick close to home.

Canadian stocks have produced decent, if patchy, results, while U.S. equities have soared into the stratosphere. In contrast, the rest of the world has turned into a graveyard for investors' hopes.

The next few years, however, are likely to present a far different picture. Based on current valuations, Canadians will have to venture further afield and become far more adventurous in pursuit of gains.

Some of the most tempting payoffs are likely to lie in the world's grittier locales – places such as Poland, Russia and Turkey. In an age of near-zero bond yields and frothy stock markets in the United States and Canada, it's the globe's emerging economies that offer the best chance of making your retirement dreams come true.

Of course, investors have heard versions of this chant before. At the turn of the millennium, the notion of investing in the BRIC countries – Brazil, Russia, India and China – was all the rage. The financial crisis brought that fad to a crashing halt.

But this time around, the call is based not just on the relative attractiveness of up-and-coming economies, but also on growing concerns that North American markets are priced to deliver only piddling returns over the next few years.

"For people with a reasonably long horizon of, say, three to five years, I would expect emerging markets to be way better than a standard mainstream developed-markets portfolio," says Rob Arnott, chairman of Research Affiliates LLC, a market intelligence firm in Newport Beach, Calif.

"Investors need to get comfortable with being less comfortable with their asset allocations," agrees Adam Butler, chief executive officer of ReSolve Asset Management, a money manager in Toronto that uses exchange-traded funds to build globally diversified portfolios.

"Given yields on North American bonds and high North American stock valuations, investors are unlikely to be able to achieve the returns they need over the next 10 to 15 years" to fund their retirements unless they venture into emerging markets, Mr. Butler argues.

Emerging-market stocks are undeniably cheap. Measured by many of the most common investing yardsticks – share prices to earnings, share prices to sales or share prices to book values – they're bargains compared with their U.S. and Canadian counterparts.

More advanced metrics underline that cheapness. For instance, one way to assess the relative costliness of various stock markets is by comparing each country's benchmark with the average real earnings of the underlying companies over the previous decade.

This approach, developed by Yale economist Robert Shiller, evens out cyclical peaks and valleys and shows you how share prices stack up against a normalized level of corporate profits. The resulting number goes by an awkward name – cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, or CAPE – but the message it delivers could not be clearer.

U.S. stocks, at more than 26 times normalized earnings, are screamingly expensive. Canadian stocks, at more than 20 times typical earnings, are only slightly less so. But a slew of emerging markets, including Russia, the Czech Republic, Turkey and Brazil, appear unusually cheap, with CAPE ratios of 10 or less.

To be sure, these countries are cheap precisely because they're risky. Many emerging markets are politically unstable. Several have troubled economies. Most suffer from corruption.

But none of those problems are exactly new. What is unusual is the size of the valuation gap that has opened up between emerging markets and U.S. stocks in particular.

"Over the past few years, the only global market that has produced meaningful positive returns in U.S.-dollar terms are U.S. stocks," Mr. Butler says. Wall Street rebounded strongly after the financial crisis and has gained an average 7.7 per cent a year since then. In contrast, other stock markets – including Canada's – lost ground between 2008 and 2016 when measured in greenbacks.

This prolonged period of outperformance by U.S. stocks is out of the ordinary. More typically, various types of assets take turns leading the pack.

To gauge just how unusual the current patch is, Mr. Butler has gone back over the past 90 years and charted, year by year, how emerging markets' returns have stacked up against U.S. returns over the preceding five-year stretch. Right now, the relative performance of emerging markets versus Wall Street has sunk to the 15th percentile of historical readings, an extremely low level, which suggests that an emerging-markets rebound is likely.

How big a rebound? GMO, a widely followed money manager in Boston, says its economic models indicate that large U.S. stocks are likely to lose 3.1 per cent a year over the next seven years, while emerging markets stocks produce average annual gains of 4.4 per cent.

Mr. Arnott's firm, Research Affiliates, also sees a big gap in returns. It estimates that U.S. stocks are poised to produce real gains of less than 1 per cent a year over the next decade. In contrast, emerging-market stocks are likely to generate average annual real returns of 7.2 per cent a year, it says.

Mr. Arnott, a well-known finance thinker, began pounding the table for emerging market stocks a year ago. Since then they've risen strongly, but he believes their gains have just begun.

"The investment community seems largely unaware of just how cheap emerging market assets have become as a result of a multiyear bear market that appears to have ended in early 2016," he wrote in a paper in December.

It's not just valuation that makes emerging markets so attractive, Mr. Arnott says. North American investors also benefit from being able to buy foreign assets in currencies that appear unusually cheap compared with the greenback or loonie.

Gauges of purchasing power parity, which rank currencies by how much the same products and services cost in each country, indicate that most emerging market currencies, except the Brazilian real, are seriously undervalued. As a result, emerging market currencies are likely to gain about 3.9 per cent a year versus the U.S. dollar over the next decade, Mr. Arnott says.

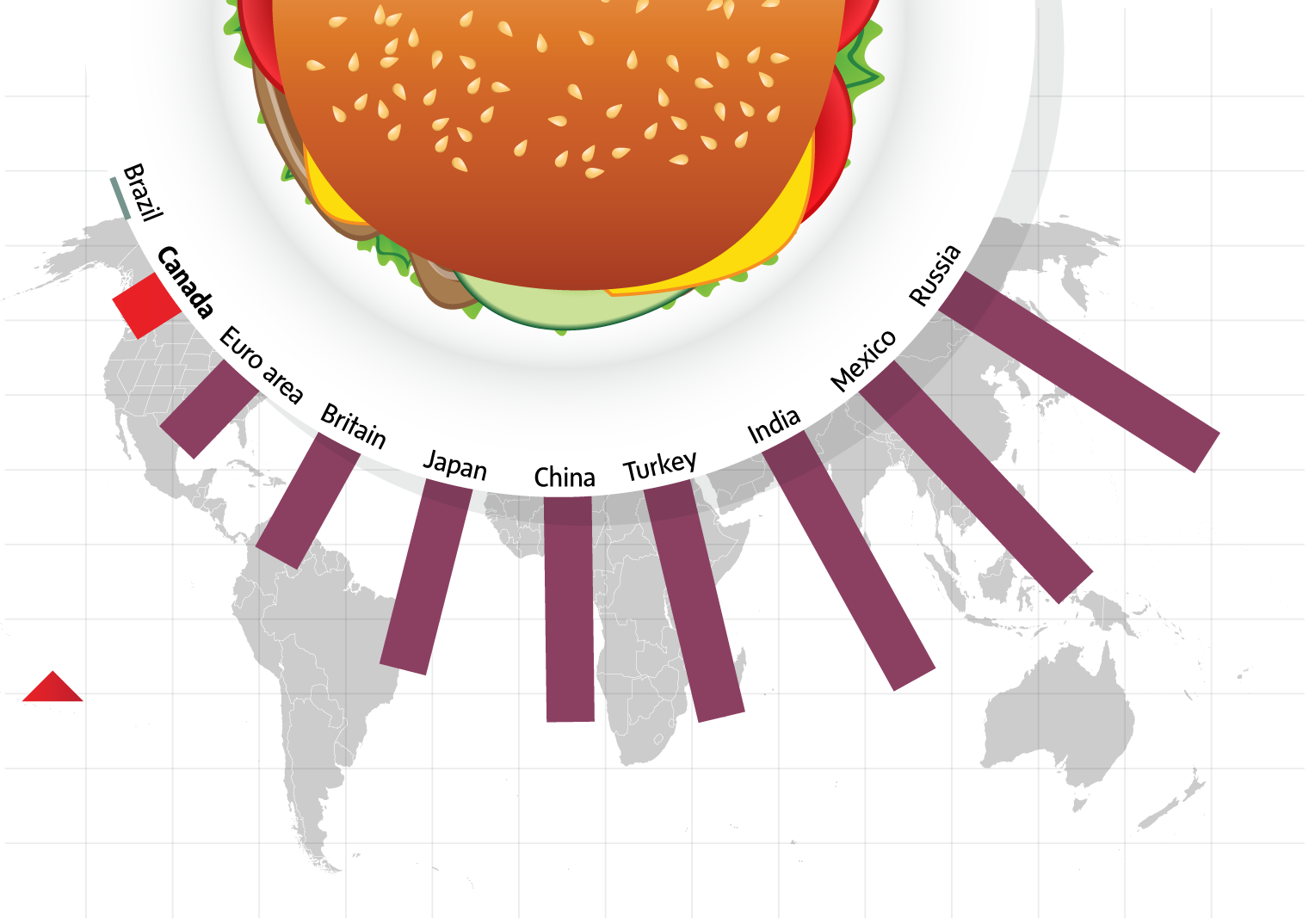

‘Big Mac’ Index

Index created by The Economist to gauge

whether currencies are under or overvalued versus

the U.S. dollar based on the price of McDonald’s

iconic burger in different currencies

Jan. 2017

Country

% under or overvalued vs. $U.S.

Brazil

+1.1%

Canada

-10.9%

Euro area

-19.7%

Britain

-26.3%

Japan

-35.6%

China

-44.1%

Turkey

-45.7%

India

-50.8%

Mexico

-55.9%

Russia

-57.5%

+1.1

-10.9

Percentage under or

overvalued vs. $U.S.

Jan. 2017

-19.7

-57.7

-26.3

-55.9

-35.6

‘Big Mac’ Index

-50.8

Index created by

The Economist to gauge whether

currencies areunder or overvalued versus

the U.S. dollar based on the price of McDonald’s

iconic burger in different currencies

-44.1

-45.7

‘Big Mac’ Index

Index created by

The Economist to gauge

whether currencies are

under or overvalued versus

the U.S. dollar based on the price of

McDonald’s iconic burger in different currencies

Country

% under or overvalued vs. $U.S.

Jan. 2017

Brazil

+1.1%

Canada

-10.9%

Euro area

-19.7%

Britain

-26.3%

Japan

-35.6%

China

-44.1%

Turkey

-45.7%

India

-50.8%

Mexico

-55.9%

Russia

-57.5%

+1.1

-10.9

Percentage under or

overvalued vs. $U.S.

Jan. 2017

-19.7

-57.7

-26.3

-55.9

-35.6

-50.8

‘Big Mac’ Index

-45.7

-44.1

Index created by The Economist to gauge

whether currencies are under or overvalued

versus the U.S. dollar based on the price

of McDonald’s iconic burger in different currencies

So why isn't everyone jumping into this trade? One reason is that, until the past year, emerging markets had produced generally dismal results since the financial crisis. Investors tend to follow momentum and the United States has been the star performer of recent years.

Emerging markets also face the prospect that the new Trump administration will take a tough line on trade and impose new taxes or tariffs that would hurt developing countries.

On top of that, the Federal Reserve seems ready to raise interest rates this year as the U.S. economy continues to strengthen. Rising U.S. rates are often bad news for emerging markets because they lure money back to American coffers.

"Financial markets in the emerging world have maintained their strong start to the year," John Higgins of Capital Economics says. "But we don't expect this to be sustained, as the Fed resumes its tightening and geopolitical uncertainty persists."

He predicts that emerging-market currencies will weaken slightly against the greenback this year, while emerging-market stocks are likely to do little better than tread water.

Many other money managers feel the same way and for good reason. Valuation gaps, such as the one between emerging markets and North American markets, tend to close slowly and in unpredictable ways. But fans of emerging-market investments remain convinced that the long-term path is headed upward, even if there some twists along the way.

All the current concerns are already well publicized and fully reflected in market prices, Mr. Arnott argues. For that reason, it would require very little to send emerging markets higher.

"The narrative out there is that Trump is going to be terrible for emerging markets … 95 per cent of investment professionals seem to believe the dollar is headed higher and emerging markets are headed lower," Mr. Arnott says. "I believe the opposite."

As the debate demonstrates, investing in emerging markets involves a tolerance for volatility. Inevitably, there will periods in which you will lag behind your peers. "You have to deal with the potential pain of underperforming when Canadian stocks are on fire and all your friends are high-fiving one another at dinner parties," Mr. Butler cautions.

One way to keep the faith during such trying times is to remind yourself that emerging economies account for roughly a quarter of global output, he suggests. Everything else being equal, it makes sense to have a portfolio that reflects that reality.

The easiest way to invest in these up-and-comers is through any of several exchange-traded funds that offer a diversified collection of emerging-market stocks. For the most part, it doesn't make sense for most investors to try to pick individual countries.

How heavily should you bet? Mr. Arnott suggests a typical investor might want to devote up to a fifth of his or her portfolio to emerging markets.

"These economies aren't going to disappear," he says. "They're cheap. The yields are high. And if they underperform for a year or two, are you really going to freak out if your allocation is only 10 to 20 per cent?"