Irma Kniivila/The Globe and Mail

Facts & Arguments is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide

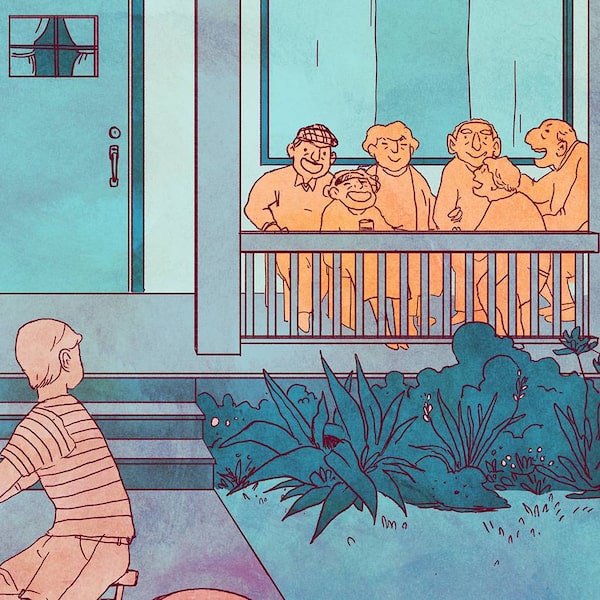

A few years ago, four friends began a conversation: Here we are in our 50s and 60s, still active and (relatively) youthful, but all moving toward the day when we can no longer cling to our cherished independence. Retirement homes seem unappealing, nursing homes a last resort. Why not live together and support each other?

It was casual at first, a bit of a joke. But we kept coming back to it. Finally, a few months ago, we went off for a weekend together to come up with a plan.

We began with our reasons for wanting to consider this seemingly offbeat idea. What attracts us to living together?

First, community. André Picard, among others, has written about the extensive research showing that community is vital to health. Being connected – to family, friends, neighbours, a community group, a running club, a mosque – can add years to your life, studies have found.

Second, a smaller carbon footprint. A smaller home envelope to heat and cool and a shared kitchen with fewer appliances than separate houses mean fewer greenhouse gases.

While affordability is not the key driver of our plan, we do expect living together to be more economical than our current, independent living arrangements.

Gradually, a rough plan came into focus. The house should have a front porch, one of us said (zeroing in on essentials!). It has to be downtown, we all agreed – downtown, walkable and close to transit.

Over the course of our weekend retreat, the conversation took some radical turns. Initially, we had imagined a series of neighbouring condos or other self-contained units, but as we talked further, we found ourselves more drawn to a truly shared space.

We realized, for example, that we want to eat dinner together more often than not. Most of us like to cook, and we all love to eat. So a big common kitchen is essential. We like to discuss stuff – just about any stuff – so we need places for conversation.

We have children and grandchildren, and love to entertain, so a guest suite is an obvious need. A media room. A wine cellar! As the common areas became more central to our discussion, the private areas became smaller. We now imagine each unit (person or couple) having private space of about 600 square feet, designed to suit individual preferences. Naturally, everything will be designed to accommodate “aging in place.”

Irma Kniivila/The Globe and Mail

At the end of the weekend, we had a three-page “proposal.” Confidently, we sent off a series of e-mails to friends who we thought might be interested.

Crickets.

Gradually, we realized that our months of casual conversation and our weekend of focused discussion had led us to ideas that might seem rather startling to anyone hearing them for the first time. It was almost as if we had suddenly interrupted a polite afternoon tea by suggesting group sex.

Our friends didn’t know how to react. “Lovely to hear from you,” one reply read, avoiding any mention of our proposal. “Hope to see you soon.”

Okay, maybe we should have eased into it more.

Others picked up on the architecture but not so much on the community. “Really interesting idea. We might consider it when we can’t manage the stairs any more.”

Okay, maybe we could have explained that part better. It’s not about the stairs.

Barring the unforeseen, each of us has decades of healthy living ahead of us. We don’t yet need any physical accommodations to our living space. So, why now? Why not wait until the stairs are too much for us? Simply put, it takes time to grow old together; it takes time to form community.

We have seen parents and older friends reluctantly accept the move into a retirement house full of strangers when they felt there was no other choice. But hanging on until there’s no choice can become a trap.

I recently heard about an elderly couple still living independently while coping with disabilities. He’s blind, she’s beginning to show signs of dementia. Together, they are fine: She can see where they are, he can remember why they’re there. But their independence is precarious. If either one were incapacitated, neither could function alone.

We are choosing to form community now, while we can still run up a flight of stairs, so that later, when our steps are more tentative, we will have friends within reach.

Of course, we also have our share of the baby-boomer attitude that says, if you don’t like the choices on offer, demand something else. Not happy with retirement homes? Fine, we’ll reinvent them for ourselves.

However, this is not truly new, it’s a modern variation of the extended family that was common a few generations ago. It’s a bit countercultural, in the face of the North American ideal of independence. We’re okay with that. We have come to see interdependence as more desirable.

So, we’re continuing to explore the idea and have created a Facebook page, @CohousingForCreativeAging, in the hope of expanding the conversation – and, perhaps, the community.

Douglas Tindal lives in Toronto.

Illustration by Irma Kniivila.