Facts & Arguments is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide.

It is 11 o'clock on a tepid Friday night in early June, and I'm holding a piece of a child's brain in my hands.

I've just finished my freshman year at the University of Maryland and am interning for the summer in the Monje Lab, which has just received a postmortem tumour donation.

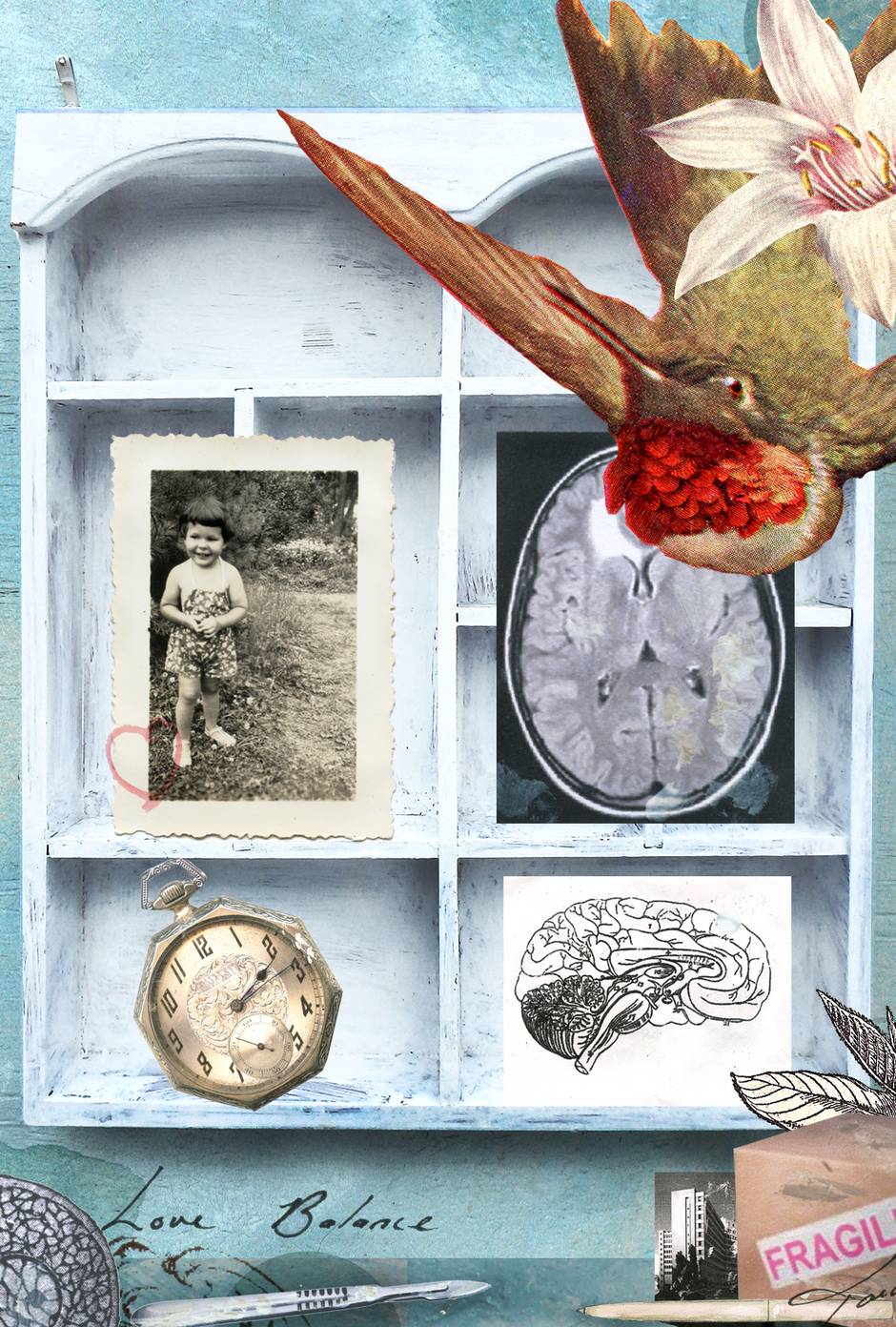

The lab studies diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), a type of pediatric brain tumour that is uniformly fatal. I am new in the lab, and this is my first donation. The scene that unfolds in front of me is controlled chaos: people darting into biological hoods clutching tubes labelled DIPGXX; heels clacking on the linoleum floor; calls of "Do we need more ice buckets?" and "Where's that last batch of salt solution?"

Michelle Monje walks in. She's a young principal investigator at Stanford University, and this is her lab. With a husband also in neuroscience, three children, a clinical practice in neuro-oncology and a recent publication in the journal Science under her belt, Michelle is an anomaly in the science world because of her ability to balance work and home life. She has dedicated her life's work to curing DIPG, and in recent years has developed the world's first DIPG cell lines.

It hasn't been an easy task: This type of tumour cannot be surgically removed because it mixes with healthy tissue in a part of the brain that regulates such imperative bodily functions as heart rate and breathing. The only tissue available for research comes from postmortem donations. These samples, often flown in from across the United States, are notoriously hard to work with. They may not arrive until days after the child has passed, so many of the cells may be dead. Recently, one sample was stuck at Houston airport for 24 hours, rendering it unusable by the time it reached the lab.

Michelle pulls me aside to show me pictures of the intact tumour. "I have to admit that these images always make me feel like I've been kicked in the gut," she says. "I was sitting on the couch with my kids when the first picture from the pathology technician arrived. It was a massive tumour. I was hit by such a profound sadness and feeling of defeat."

But, faithfully, she came in to oversee the lengthy process unfolding before us. She shows me the basilar artery, which the tumour has wholly engulfed. Large and in perfect HD on her smartphone screen, the tumour somehow seems less abstract to me. “The hardest ones come from children I know,” she goes on. “When the donation is from a child I haven’t met, I wait until after the donation to look at the pictures and Facebook pages. I function better if I have more distance. And then afterwards, in a quiet moment, I look through all of it and mourn.”

An hour in, the frenzy breaks and the room settles to a comfortable pace. Someone turns on a nineties rap radio station. Humsa, a PhD candidate who is tonight’s point person, calls across the room for another tube of tissue. She sits in the faint glow of a biological hood, between two other students, all three using scalpels to chop brain tissue into the tiniest pieces possible.

At 3 a.m. I am watching Grant, a medical PhD candidate, prep cells. Usually an infectious ball of enthusiasm, he’s more reserved at this late hour. “Of course it’s sad,” Grant says as he pours a tissue sample into a conical tube. “It’s a kid dying. If you don’t think it’s sad, well then, you aren’t thinking about it hard enough.”

The next Monday, we get an e-mail with no body text and the subject line “DIPGXX’s Family Coming For a Visit.”

They arrive around noon, a mother, father and child. Michelle brings them into the lab and shows them their child’s cells under the microscope. As I look at the family from across the bench, I can’t help thinking about how we have this cell line, this last living piece of their child, and I don’t even know the child’s name. I’m not sure I want to.

All of us walk the line between empathy and apathy. Empathy is a fickle friend, both a motivator and a quick path to burning out. Is it worth it to emotionally invest in the people our work could help? Or is it easier to detach, to separate ourselves from our feelings? Does it make us better scientists? Does it make us better people?

These questions have been asked for centuries. I’m 19 years old, and don’t possess enough hubris to say I can answer them. But I do know this: As scientists, we love the simplicity of black-and-white answers. Science ultimately separates all pieces of information into two groups: the truth and everything else. But this is no place for binary answers: The truth, and ultimately life, defies simplicity.

Grant, Elizabeth and I are eating lunch when Michelle brings the family out of her office. As they walk down the hallway, becoming smaller and smaller, we share a knowing glance. For a moment it isn’t about failed experiments or high-impact publications. It’s about a life, a group of lives, just as complex and varied as our own, that will never be the same.

Isobel Hawes lives in College Park, Md.