The lobster salad at Toronto's Nota Bene has been on the menu since George Bush's son was U.S. president (that is, 2008). So when the dish of steamed Nova Scotia lobster, maple-smoked bacon, preserved dill, avocado and buttermilk ranch dressing disappeared in early fall, regulars noticed.

Servers told querying patrons that the quality of lobster was not up to par. The harder truth was that the crustacean had gotten too rich for our blood. In the past five years, co-owner David Lee watched per-pound cost rise from around $9 to $12. Even if Nota Bene charged $29 for the appetizer, the dish would be unprofitable.

"The price is just crazy," Lee says. "And there's only so much the guest will pay for lobster." When it reached $16 a pound in September, he took the salad off the menu.

People love to tell you, with the fanfare of revealing that Michael Caine's real name is Maurice Micklewhite, that lobster was once so inexpensive and undesirable that it was fed to servants and prisoners.

However, this is not back in the day. And to anyone fewer than 100 years old and not living on the Atlantic, lobster is a delicacy.

A deckhand stacks a lobster trap during an early morning lobster fishing expedition.

Scott Munn/For The Globe and Mail

North Atlantic lobsters (a.k.a. Homarus americanus, American lobster, Boston lobster or Canadian lobster), which are indigenous to our eastern shores, average one to one and a half pounds. Cooked, they contain between 20 per cent to 30 per cent meat. If the cost at the fishmonger is $15 a pound, that makes a pound of meat worth about $60.

Even if you're finding a secondary use for the shells – lobster bisque, paving your driveway bright red – that's an indulgence.

"The fishers have gotten a better-than-warranted price over the last 15 months and we've had to pass that on to the marketplace," says Stewart Lamont, managing director of Tangier Lobster Co. in Nova Scotia.

Lamont fell into the lobster trade after getting degrees in political science, public administration and law. He identifies three factors for the rising price: international demand, the weak Canadian dollar and the naturally competitive nature of the lobster sector.

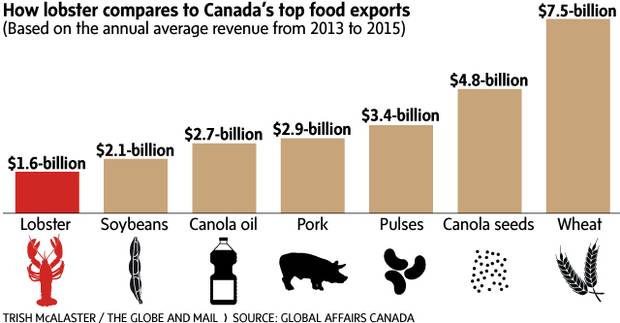

Let's start with demand. Canadian fishers pull 200 million pounds of lobster from Atlantic waters every year. In 2015, the sale of lobster exports, whether live, frozen, boiled, steamed, tinned, in brine or otherwise, totalled just more than $2-billion. Our major trading partner for the ocean creatures is still the United States, and between 2011 and 2015, lobster exports from Canada to the United States increased 38 per cent.

In the same time, direct sales from Canada to China have more than quadrupled, from 1.3 million to 5.8 million pounds. Lamont says that's where much of the U.S. purchases end up, too.

"Upwards of 80 per cent of the lobster from Atlantic Canada goes to America," Lamont says. "Many of [the companies importing our lobster] turn over the next day and export it to Europe or Asia." He recently arranged a distribution deal in Guangzhou, the third-largest city in China, with a population of about 13 million.

Increasing demand aside, price fluctuations are a little more complex than whether the ocean creatures are in- or off-season.

"The lobster business is a funny business," says Dan Donovan, co-owner of Hooked, a seafood retailer and wholesaler in Toronto. "It has nothing to do with when the lobsters are the best." He says Nova Scotia's coast is divided into zones called Lobster Fishing Areas: To evenly distribute revenue among fishing communities, the province has assigned each LFA a period in which it's allowed to harvest lobster, going clockwise.

During each LFA's season, lobster is caught more quickly than it can be shipped. So live crustaceans are stored in tanks with a lower temperature and basically put into hibernation. These are called tubed lobsters.

"As you get deeper into the tubed period, eight or nine months, that's where you get these swings in the pricing of lobster," Donovan says. (Lamont prefers the term "individual slot long-term storage" to "tubed," and says the size of stored lobsters also affects price.) Despite its higher price, the quality of tubed lobster is likely what made Nota Bene's Lee unhappy. "There's no scientific proof that the quality degrades," Donovan says. "But logic dictates that it's not as high-quality as what was freshly caught eight months ago."

Fishermen prepare their boats for the lobster season in Woods Harbour, N.S., on Saturday, Nov. 26, 2016.

Andrew Vaughan/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Bronwen Clark of Rodney's Oyster House (a Toronto restaurant that is also a seafood wholesaler) is one of Nota Bene's suppliers. She believes the price will come down a bit in the short term, as one LFA closes and another opens up. But long-term, the cost will continually rise.

While Canadians grouse about those back-in-the-day prices, Clark says the rising middle class around the world is willing and able to pay for things that we can't or won't.

"We were recently in China. The amount of lobster those guys go through drives the price," she says. And while some parts of the world prize the quality of Canadian lobster, China likes it mainly because it's cheap and abundant.

Broker Andy Wang, who lives in Vancouver, buys Nova Scotia lobster from people such as Lamont and sells it to wholesalers in China, where they refer to it as "Boston lobster," despite its provenance. "If it's Chinese New Year, Moon Festival, anniversary, the problem is not the price," Wang says. "The problem is only about the quantity. The middle class is a huge group of people. If they purchase, it will be huge quantity."

He says that Chinese buyers prefer Australian lobster, but it's often twice as expensive and in shorter supply. Song Xin, executive chef at the Fairmont Beijing, told me he ranks Australian lobsters as the best but buys Canadian for the price. He serves eggs Benedict with Canadian lobster hollandaise sauce and sautéed Canadian lobster with salted egg yolk.

Even though U.S. president-elect Donald Trump is threatening to impose trade tariffs, one wonders what will happen to the lobster market. Lamont isn't worried about the North American free-trade agreement being torn up. "Trade agreements are astonishingly difficult to negotiate and put in place," he says. "And almost as difficult to tear up and replace." That seems reassuring – then again, the unprecedented keeps setting precedents under the upcoming president.

Lobster boats head from West Dover, N.S., on Nov. 29, as the lucrative lobster-fishing season on Nova Scotia’s South Shore opens.

Andrew Vaughan/THE CANADIAN PRESS

In any case, global demand makes it unlikely Canadians will find Canadian lobster more affordable any time soon. "I was in Italy a few weeks ago," Donovan says. "The Eataly store had cooked North American lobsters. They were €70 [$100] a kilo. It's a luxury in the caviar range. Canadian lobster has a cachet on the international market that Canadians don't understand."

Meanwhile, the lobster salad has gone back on the menu at Nota Bene. It probably won't stay there long.