In the critical-care unit at Toronto's Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, patients hover between life and death. Nurses and doctors do their best to make them comfortable and stable in hopes of aiding recovery.

And yet the physical environment where they work is constantly undermining their efforts. The open-concept design, which dates back to the Crimean War, makes it more difficult to contain the spread of hospital-acquired infections. The noise from machines, staff and overhead announcements constantly interrupts rest. Fluorescent lights and little access to windows keep patients cut off from the world, unsure if it's day or night.

More from the #TheHospital

- Part 1: How one hospital is dealing with Canada's aging population

- Part 2: How hospitals are on the front lines in a new era of germ warfare

- Part 4: Life’s last milestone: Why a ‘good death’ matters

- Part 5: Why the future of health care may depend on tearing down the hospital

"If we could start fresh, we would design this place entirely differently," says Dr. Brian Cuthbertson, chief of Sunnybrook's critical-care department.

This sort of outdated health-care architecture tends to be the rule, not the exception. Throughout the 20th century, hospitals were constructed to suit the needs of caregivers, not patients, says Robyne Maxwell, director of care delivery model redesign for Island Health in Victoria, B.C. The physical space wasn't considered an integral part of the healing process.

But that line of thinking is rapidly becoming part of the Dark Ages of medicine. The catchphrase today is "evidence-based design," which takes as its starting point that patients' surroundings have a major impact on outcomes and on staff's ability to do their jobs more efficiently. Among the key findings: Numerous medical studies have shown that single-patient rooms, noise-absorbing floors and ceilings, exposure to natural light and reduction in overhead announcements encourage rest – and help patients get home sooner.

At Sunnybrook, pockets of the hospital show a glimmer of what's to come. In the hospital's new neonatal intensive care unit, which opened in 2010, all 48 beds are housed in single rooms, with the exception of two rooms designed for twins. Glass walls allow the nurses constant visual contact with their tiny patients. Rooms are darkened to reflect research that shows NICU babies thrive best without the lights on. And each room has a separate entrance for parents, which allows them to visit their children as much and as often as they wish.

There are also "negative pressure" rooms that have separate ventilation systems, allowing patients with infectious illnesses to be segregated. The department is further divided into four pods that, if necessary, can be isolated from each other in the event of an outbreak. There are scrub sinks outside every patient area – the only place in the hospital that can make that claim.

Since the department has opened, there have been no outbreaks of chicken pox or other infectious agents, which was a fact of life in the old department.

There are signs that this sort of design will one day dominate the country's hospitals. The Canadian Standards Association now recommends that at least 80 per cent of the bedrooms in new hospitals be single-patient units. And new institutions, such as the Royal Jubilee Hospital in Victoria and the redevelopment of Toronto's Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, have won worldwide accolades for their incorporation of patient-friendly design.

The challenge is finding ways of incorporating evidence-based design into buildings that were constructed decades ago. Retrofitting existing institutions takes a lot of money and a commitment to spend more up front to save in the long run.

It's not an easy sell. Dr. Michael Gardam, director of infection prevention and control at the University Health Network in Toronto, says updated wings and new hospitals should be designed so that 100 per cent of patient rooms are private. But few, if any, do that, because hospitals are "addicted to that revenue stream." Having only single-patient rooms costs more to build, takes up a larger footprint, and also prevents hospitals from charging patients who want to pay to upgrade to a single room, Dr. Gardam notes.

"The argument is you're going to recoup that [revenue] over the 40-year lifespan of the hospital," he says. "Governments don't think in terms of 40-year plans. They think in terms of now."

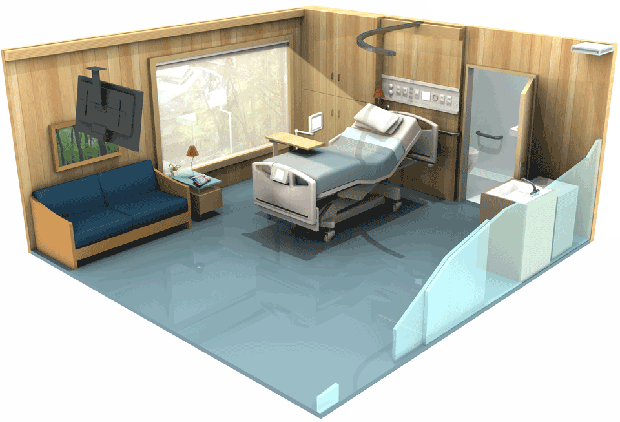

ROOM FOR ONE

NATURE, LIGHT AND ENTERTAINMENT

A BED AND CONTROL CENTRE, WITHOUT RAILS

QUIET, CLEAN AND PRACTICAL

BLUEPRINT TO A BETTER HOSPITAL

2. RADIAL DESIGN Advocates of evidence-based design say circular layouts decrease the amount of walking time by nurses and other health professionals, and may be particularly helpful for patients with dementia who tend to wander.

3. DECENTRALIZED NURSING Instead of one large nursing station, spreading working stations throughout a unit enhances nurses’ ability to monitor patients, decreases the amount of time they spend walking, and also reduces noise levels.

4. HOSPITAL GARDENS Numerous studies have concluded that gardens can substantially lower stress levels, which can lead to faster recovery times and improved patient outcomes.

5. EASY ACCESS TO PARKING Providing parking that is well-located in relation to the hospital and easily accessible from main entry points is linked to improved hospital satisfaction and reduced stress.