In Canada, we like to joke that the mosquito is the national bird.

But in most of the world, mosquitoes are no joking matter.

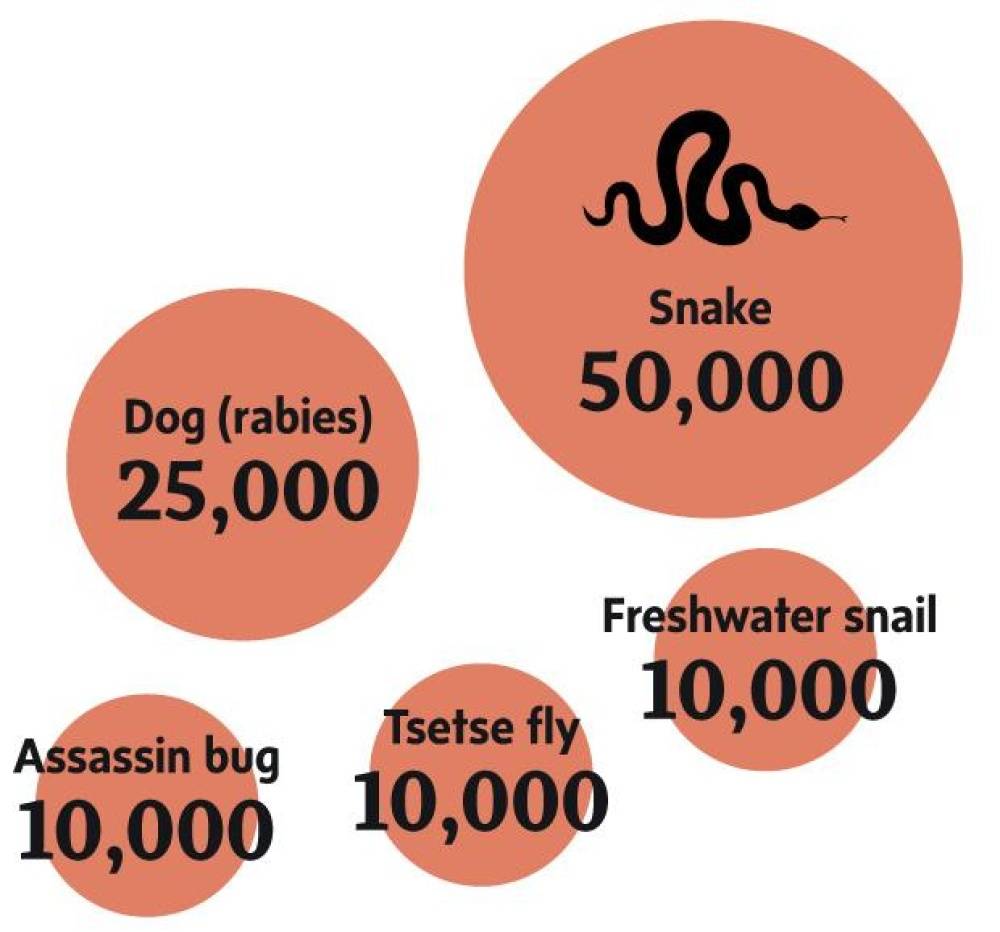

They are, in fact, the deadliest creature on the planet, responsible for about 725,000 deaths a year. By comparison, sharks kill about 10 people annually, and snakes are responsible for 50,000 deaths.

Mosquitoes are lethal because they are very efficient carriers of pathogens that cause deadly illnesses like malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, West Nile, Rift Valley fever, chikungunya fever, and various forms of viral encephalitis – Japanese, Eastern equine, St. Louis, La Crosse, to name a few.

Number of people killed by animals a year

Malaria is, by far, the most dangerous mosquito-borne illness. Female Anopheles mosquitoes pick up parasites – there are four kinds, but Plasmodium falciparum is the most deadly – by feeding on human blood and infecting others when they inject saliva as part of the feeding process. (Only female mosquitoes bite.)

Malaria alone kills an estimated 630,000 people a year, and incapacitates 200-million others for various lengths of time. That’s actually good news, because mortality rates have fallen by more than 40 per cent in the past decade, thanks to determined campaigns by groups like Roll Back Malaria and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

There is no malaria transmission in Canada; the temperate form of the disease that was here has been controlled for about a century and was eradicated in the 1950s with DDT spraying.

But, at one time, it was a common illness here: In the 1820s and 1830s, about two-thirds of workers digging the Rideau Canal between Kingston and Ottawa contracted malaria, and there were an estimated 1,000 malaria-related deaths.

Today, malaria is a threat principally to overseas travellers; about 15 Canadians develop a life-threatening case each year.

There is no vaccine, but there are medications that can be taken to reduce the risk of infection.

Another tropical illness that is a growing threat to travellers is dengue fever (also known as breakbone fever), the most dangerous form of which is hemorrhagic dengue fever.

Dengue infections – spread by Aedes mosquitoes – have risen dramatically in recent years, estimated to affect 100-million people annually.

Like malaria, dengue can be incapacitating, and kills about 25,000 people a year.

Dengue fever has become a growing problem in the Carribean, a favourite destination for Canadian tourists, so it is getting a lot more attention.

There is no vaccine or medication to protect against infection, and no specific treatment for the infected, other than relief for the pain.

Chikungunya fever is another mosquito-borne illness, one that is spreading at an alarming rate in the Americas, particularly in tourist hotspots such as Cuba and St. Martin.

It is very similar to dengue, causing high fever and joint pain, and is also spread by Aedes mosquitoes.

In a temperate climate like Canada’s, mosquito-borne illnesses are far less common.

The greatest domestic danger is West Nile virus, which is spread by Culex mosquitoes who feed on the blood of infected birds, then subsequently bite humans.

The first human cases in Canada occurred in 2002, and there were 14 deaths that year, causing a great deal of alarm.

But only one in every 150 people infected with West Nile virus will develop serious symptoms. There have been few deaths in recent summers; physicians have become more adept at spotting and treating the illness.

There has also been a large die-off of infected birds, and many people have developed immunity after suffering a mild case of West Nile.

The other mosquito-borne illness known to spread in Canada is St. Louis encephalitis but, after large outbreaks in the 1970s, the number of serious cases has been minimal.

What all these illnesses have in common is that they are largely preventable with some pretty simple measures.

Mosquitoes breed in stagnant water, so the key is to eliminate or minimize standing water near where people live.

That means storing flower pots, watering cans, wheelbarrows and the like upside down; routinely replacing water in bird baths and wading pools; aerating and cleaning swimming pools; cleaning gutters; and landscaping to get rid of puddles.

During mosquito season – May to September in Canada – it’s a good idea to use insect-repellent containing DEET, and wear long sleeves and pants, especially at dusk when the most pesky mosquitoes are active.

There are 2,500 species of mosquitoes worldwide, and 82 species in Canada.

Only a small fraction of them feed on humans. While we tend to think of mosquitoes as bloodthirsty, their principal source of nourishment is sugar from the nectar of flowers.

However, there is nothing sweet about the growth and spread of mosquito-borne disease, which is largely a byproduct of climate change.

In the years to come, as deadly diseases like dengue and Chikungunya fever – and maybe even malaria – move closer to our borders, mosquitoes will shift from being summer pests to a real public health threat.

Canadians may have to start taking the little buggers more seriously.