Research labs across Ontario are full of ingenious – and even life-saving – inventions. Unfortunately, many of them never make it to market.

“What we often find is the person who invents it – the principal investigator or the researcher – they have a full-time job and that’s to do more research. So sometimes these things don’t get commercialized or made into a product anyone can use,” says Alison Fenney of the Ontario Brain Institute.

To rescue great ideas from eternally gathering dust, the institute started an annual competition in 2012, similar to CBC’s Dragons’ Den, in which young scientists pitch their neuroscience-related inventions before a panel of judges. The successful candidates each receive up to $60,000 and mentoring to help them commercialize their ideas. Each year, the OBI funds a maximum of 10 individuals, but picks only the most entrepreneurial candidates who present the most impressive ideas and who are compatible with their chosen peer group.

To date, 21 selected participants have gone through the OBI Entrepreneurs Program. Some have gone on to partner with hospitals to clinically validate their treatments or devices, while others have attracted further funding to continue developing their products and hire staff for their startup companies.

The program, co-funded by the Ontario Centres for Excellence, addresses a couple of key issues, Fenney says. First, she points out, there aren’t enough jobs in academia for postgraduate researchers in Ontario.

“So in one way, it helps provide alternate career options for graduate-trained researchers,” she says. And second, “it actually makes sure that the really great idea, the cool treatment or device, gets out of the lab and into a product that can be accessed by the public.”

From the 30 to 50 applications it receives each year, about 15 people are selected to make their pitches before the judging panel. In June, six individuals managed to win over the OBI judges to make it into this year’s program.

We asked the chosen participants to explain their ideas:

Who: Ron Gonzalez, president of the startup Avertus Epilepsy Technologies Inc.

What: A “Holter monitor” for the brain

When diagnosing heart problems, doctors sometimes require patients to wear a Holter monitor, a portable device that continuously tracks heart rhythms and records any abnormalities. Avertus has created a similarly easy-to-use, wearable device that monitors a brain’s vital signs to track epileptic seizures.

Currently, getting an epilepsy diagnosis is highly inconvenient, Gonzalez explains. Patients must go to an epilepsy monitoring unit at one of the few neurology centres in Canada, where the waiting list can be as long as 18 months.

The Avertus headset, which is a far less expensive and less cumbersome version of heavy-duty hospital electroencephalograms, allows doctors to triage their patients and determine who requires further assessment. (Compared with the hospital electroencephalograms, which are glued to a patient’s scalp and cost up to $40,000, Avertus’s device is expected to cost roughly $2,500.)

“There’s no preparation. You just flip it on top of your head,” Gonzalez explains, and the headset monitors brain activity, oxygenation and blood flow. Those measures are streamed to a physician’s tablet, from which the physician can track multiple patients at a time.

Besides hospitals and clinicians, Gonzalez believes families with children who have epilepsy may also benefit from the device. “Many parents with children with epilepsy report that they hardly ever or never feel well-rested because they’re up all night, they’re using baby monitors to monitor their children. You know, it’s horrible,” he says, noting the device may offer a better way of alerting them when their children experience seizures.

Who: Asim Siddiqi, founder of the startup Dymaxia Inc.

What: An anxiety-meter app for children with autism

As much as 80 per cent of children with autism suffer from anxiety, but they often have trouble recognizing and communicating their anxiety states, Siddiqi explains. “Just like we sometimes have difficulty ourselves recognizing when we’re kind of stress-eating and things like that, they have it a little worse than we do.”

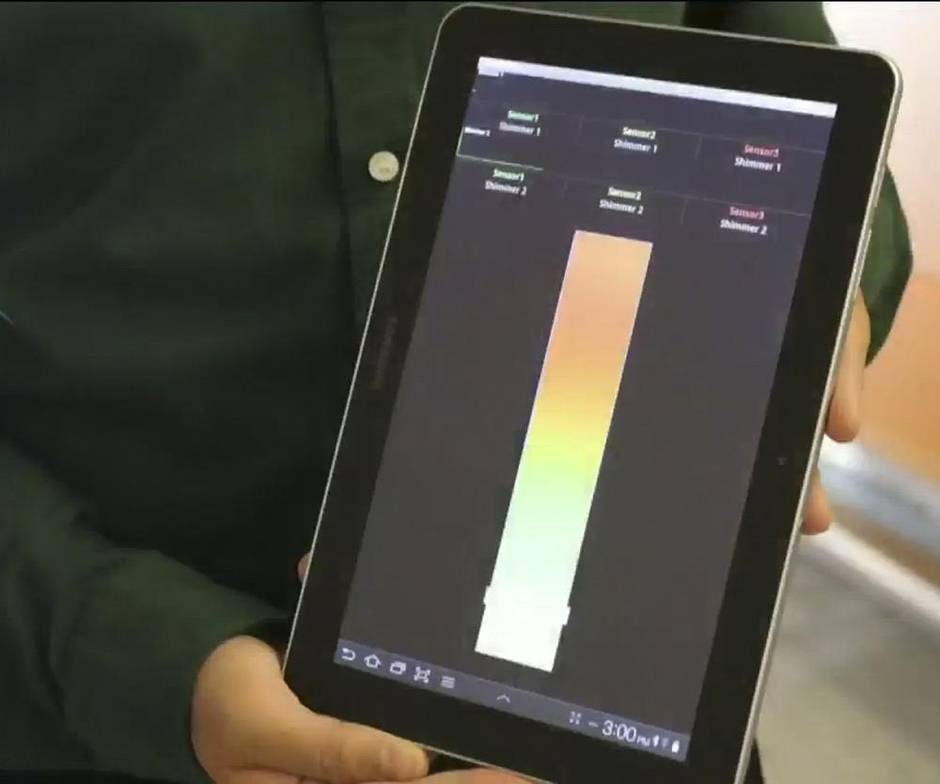

Using sensors on the body, Dymaxia’s anxiety meter picks up physiological signals, such as heart rate and skin conductance – or the amount of electric current that passes through sensors on the skin, which increases with stress and body temperature. It then processes those signals and provides feedback of the child’s anxiety state in real time on a mobile phone or tablet.

Ideally used when children are away from their caregivers, the app would alert them when they become agitated, reminding them to employ the coping techniques they learn through behavioural therapy.

“It’s providing them self-awareness,” Siddiqi says. “They need that prompt, that reminder of ‘Okay, you need to implement your therapy training.’”

Who: Salam Gabran, chief executive of the startup Novela Inc.

What: Advanced implantable medical electrodes

These are tiny devices as thin as a strand of human hair that can be implanted inside the brain, and used primarily for brain research and to develop new therapies for brain disorders. Novela’s research collaborators at the University of Toronto, for instance, have successfully used the electrodes to treat epilepsy in rats and are planning to test them on bigger animals and, eventually, humans. Epilepsy, however, is only one potential target.

“It can be used for a range of disorders,” Gabran says, explaining the electrodes can also be customized for chronic pain, tumours, Parkinson’s disease and depression.

Here’s how it works: Since these brain disorders involve the misfiring of electrical impulses between neurons, Novela’s electrodes – which are essentially “nothing but a set of wires, very tiny little wires” – send electrical signals to targeted clusters of neurons to override or cancel malfunctioning messages, Gabran explains.

Although Novela’s devices have so far been used only in animal research, Gabran is currently working on a prototype for humans.

Who: Ruslan Dorfman, chief executive of GeneYouIn

What: Predictive testing to optimize pain management and the treatment of mental conditions

If you’ve ever wondered why some medications don’t work for you, the answer may be in your genes. Individuals metabolize medications in different ways, Dorfman explains. For example, for people who lack the specific enzymes necessary to convert codeine into morphine in their livers, Tylenol No. 3 with codeine would offer no more relief than regular Tylenol.

To ensure patients get the most effective medications, GeneYouIn uses software to link their genetic test results to drug-label recommendations for about 60 common medications, including 24 anti-depressants.

“It provides personalized dosage recommendations for each client based on [their] genetic profile,” Dorfman says, noting the system is ideally used by patients, together with their doctors and pharmacists. So for those who are poor metabolizers of codeine, GeneYouIn’s program would warn against using Tylenol No. 3 and similar pain medications, and recommend alternative drugs that would work better. And for those who metabolize certain psychiatric medications more quickly, it would notify them that standard doses would be ineffective.

Who: Adrian Wydra, chief technical officer of the startup True Phantom Solutions Inc.

What: “Phantom” brains and skulls for use in research and neurosurgery skills practice and testing

Researchers and neurosurgeons need brains on which to experiment. The trouble is obtaining them. The solution? Phantoms.

Phantoms are artificial body parts made from synthetic materials. At True Phantom Solutions, Wydra has created phantom brains and skulls using polymer-based materials that behave the same as real tissues in response to ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging.

“Basically, you can do the same thing as on the real body, but you don’t hurt anyone,” he says. Plus, he adds, since they’re totally synthetic, the phantoms don’t degrade like real tissue. “They don’t need to be kept in the fridge. You can just stock them on the shelves.”

Who: Marc Fiume, chief executive of the startup DNAstack

What: A searchable genetic database

When an individual has a genetic disorder, there is usually at least one position (and sometimes a few) within the three billion places in the genome that is flawed or mutated. DNAstack creates a database or library of all the various mutations within a group of patients. An autism sequencing project, for instance, may involve collecting the genomes of 1,000 different autism patients.

“The issue is that that’s a lot of data,” Fiume says. So to navigate such a vast library of genetic

information, he explains, DNAstack has created a search engine that would allow researchers or clinicians to pinpoint the one or two or few mutations responsible for a particular disease or disorder.

Call it the Google of genetic information. Users would enter search conditions (using terms such as “male patients,” “autistic characteristics” to find potentially harmful mutations), Fiume explains, and the search engine would provide the top five lists meeting those criteria.

“Much like Google is approachable to every human who can type,” he says, “we want to make a system that’s extremely user-friendly so that you get results really quickly and you can specify the search with natural language.”