Mass-produced and mass-marketed, typically laid out according to unimaginative industry-wide formulas, most apartments coming up for sale in Toronto’s high-rises resist transformation into dwellings with contemporary flair and spatial originality. But even if a unit’s interior were more structurally malleable than it usually is, local retail sources probably couldn’t provide what’s necessary to stamp the space with a distinctive signature.

The apartment-ready artworks, outfitting and furnishings commonly available in the popular shops tend to be blandly modernist (or blandly nostalgic), and largely uninspiring. One can, of course, buy classics, such as Le Corbusier’s dining room table and Mies’s Barcelona chairs. But to fashion an entire residential scheme around such 20th-century pieces would be to recreate a venerable, but safely distant past. What would a high-rise suite that reflects the creative values and most vigorous ideas of the present look like?

This question started to nag me after a recent visit to an apartment that had been kitted out, at considerable expense, in what amounted to the Ikea style - an aesthetic that definately belongs to the last century , not this one.

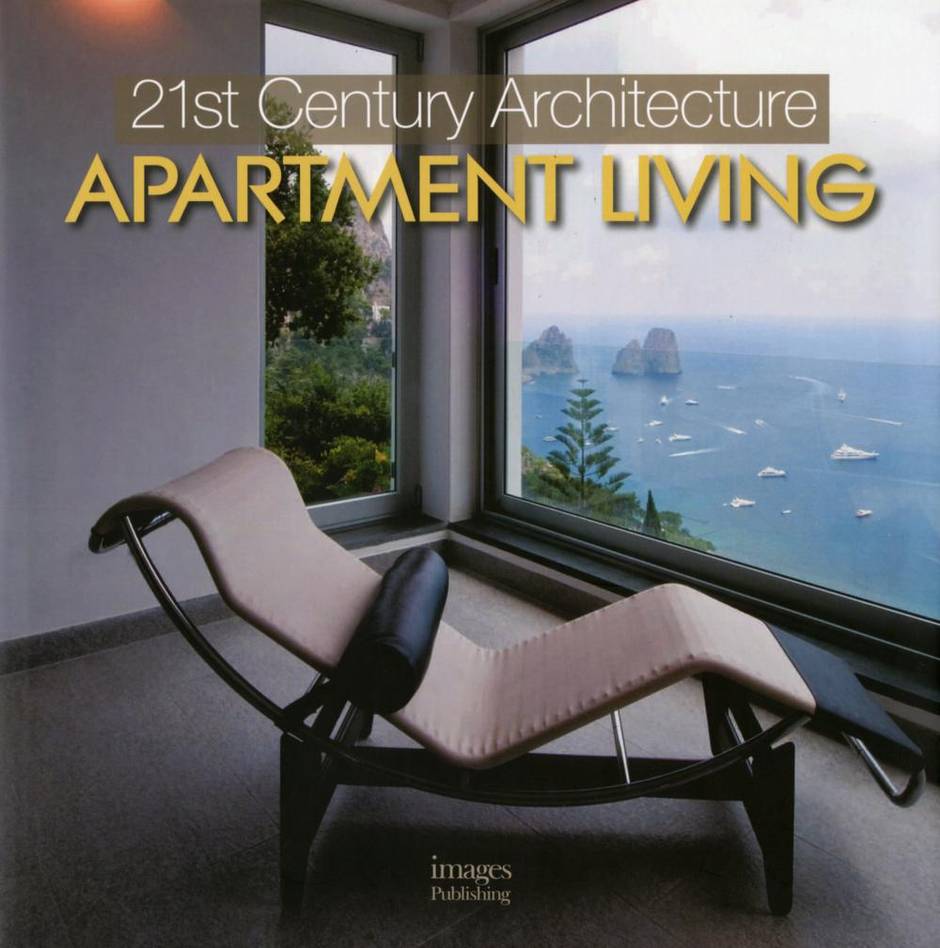

So it was that, rummaging for an answer among my architectural books and magazines, I rediscovered a portfolio called 21st Century Architecture: Apartment Living. I had glanced at this collection in 2011, when it was published (by an Australian concern called Images), made a mental note to pick it up again some day, then forgotten about it.

Fortunately, the book – available in Canada for about $35 – was still on my shelf when I went rummaging, since, as I found, it offers no fewer than 54 answers to my question about contemporary apartment design, not just one. The prolific architectural writer and editor Beth Browne has gathered into her volume documentation about that many new and recently overhauled apartments in Europe, North and South America, China and Australia, each executed by an architectural firm for a client not inclined to settle for the ordinary.

The characteristic up-tempo style of this century, if Ms. Browne is to be believed, is open, casual but alert, concerned with sustainability and partial to upholstery, to expressive and figurative painting, to luxurious bathrooms, to sensuous surfaces and textures. Attention to surface can occasionally become the driving force in the design. For a renovation in a 1950s Austrian apartment block, for instance, Atelier Peter Ebner covered every plane – floors, walls, ceilings – with a semi-abstract botanical pattern that defies the owner to put up art, but lends vivid interest to what would otherwise be blank expanses.

More commonly, interest in the skin of the apartment’s interior finds expression in deployment of sumptuous materials and unusual shapes. Architect Isay Weinfeld, in a complete overhaul of an old New York flat, lined the new rooms with richly dark wood, while UNStudio sculpted a gleaming, curvaceous loft, also in New York, out of an unpromisingly ordinary oblong of space. Contemporary designers, such schemes show, are thinking well outside modernism’s rigid, straight-sided white box, working with other geometries, imagining new ways (some of which, like wood panelling, seem old) to frame the apartment-dweller’s domestic experience.

But the general attitude of new design toward the past, unlike that of high modernism or minimalism, is forgiving, accepting. Take, for example, the 3,000-square-foot Beverley Street apartment by Toronto designers Merike Reigo and Stephen Bauer – the only Canadian project showcased in the book. In the living room of this suite, old-fashioned turquoise wingback chairs mingle comfortably with strictly modern black sofas. This is design beyond dogma.

Over the table in the Toronto suite’s otherwise austere dining room hangs a humorously flamboyant, cartoon-like chandelier – a reminder that contemporary apartment style does not take itself all that seriously, and does not consider itself the interior-design wing of a crusade to advance “good taste.” Instead, it welcomes collision and mix-up, allusion and metaphor – so long as these poetic gestures do not clutter up the place, restricting the spaciousness, the easy flow, that the style celebrates above all else.

Some of the schemes illustrated here are in brand-new towers; others (such as the one in Toronto) are revisions of spaces in long-established residential structures; still others are insertions in recently converted warehouses or factories. One or two are small; clever architects in Ljubljana worked a little miracle with a loft only 320 square feet in area. Most of Ms. Browne’s examples, however, are large, and many are dauntingly deluxe.

But her book is full of punchy, provocative design ideas that can be variously scaled, adapted and re-sized to fit any budget and lifestyle. There is a great deal here for empty-nesters about to downsize, young condo buyers furnishing their first digs – and for people who, like me, love apartment living, and enjoy seeing the ways others have discovered of doing so beautifully.