Exactly 20 years ago, the ground was broken for the Walt Disney empire’s Florida residential development known as Celebration, and you never saw such a flap.

Critics denounced the low-density scheme’s mimicry of premodernist housing vernaculars as so much nostalgia, à la Norman Rockwell. In the settlement’s small-town layout, starchier pundits sensed a conspiracy of right-wingers against the very project of modernism (which, admittedly, had seen better days) and spoke disdainfully about the “Disneyfication” of American architectural history.

Meanwhile, the authors and friends of Celebration (notably, U.S. architect Robert A.M. Stern, who master-planned it) argued that the vision was just an update of eternal, or at least very old, planning principles. Modernism’s public-housing projects and vast tracts of suburban sprawl, the defenders said, weren’t working for anyone. But the compact garden suburb of earlier times, one of Celebration’s precedents (along with the small American town) – walkable, modestly scaled, scenic, friendly – had worked well for generations of our ancestors, and it could now inspire the forms of new towns outside the city limits, and even inside them. Hence Celebration, which set out to demonstrate the validity of the old-fangled urbanism that Mr. Stern and others were advocating at the time.

Twenty years later, Mr. Stern is still fighting the modernists who attacked him and his Florida project in 1994. The enemies know he’s still there because he recently lobbed an enormous book at them – Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City, co-produced with David Fishman and Jacob Tilove – all 5.5 kilograms, 1,070 big pages and 3,000 illustrations of it. (The work comes from the New York’s Monacelli Press, and is available in Canada for about $70.)

Advertised as “the definitive history of the development of the garden suburb,” it isn’t one, since it has a tonic to dispense, not a story to tell. “Our study,” says the preface, “is written with the intention of stimulating an appreciation of the garden suburb in its various types, but it is just as importantly intended as an activist work using historical scholarship to promote the garden suburb as a development model for the present and foreseeable future.”

At the end, Mr. Stern gets to the heart of the matter. He sets up, as horror examples, Le Corbusier’s genuinely calamitous Plan Voison for the city of Paris (1925) and Frank Lloyd Wright’s equally obnoxious (and unbuilt) spectre of car-ridden sprawl called Broadacre City (1934). He then portrays himself as one of several warrior-prophets – he does not hog the saga – who sallied forth, from the mid-1970s onward, to broadcast the anti-modernist good news that ultimately came to be known as the “new urbanism.”

Other apostles of this interesting, once-controversial body of doctrine, the most marketable bits of which have been mainstreamed and muddled by developers and town planners since the 1990s and so lost their punch, include American architects Andrés Duany, his wife Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and Peter Calthorpe. Among the few non-American practitioners to receive praise in this final section is the Luxembourgeois designer and planner Léon Krier, whose Poundbury, a neo-traditional suburb of Dorchester, England, was done for the Prince of Wales.

In the 1,000 or so pages between the preface and the epilogue, the writers describe, tour-guide style, several hundred built projects, a few unbuilt ones, and some (like Gary, Ind.) long ago disfigured beyond recognition. The thorough, encyclopedic annotations go deep and wide. The earliest “fully realized” example of the garden suburb documented here is John Nash’s Blaise Hamlet (1811), near Bristol, a retirement community for former servants; the popularity of the type peters out during the Second World War, to be succeeded by the sort of suburbia that is not the subject of this book. All the famous British and American instances of planned exurban arcadias, and a great many obscure or forgotten ones, are featured in Paradise Planned: Nash’s extension of London past Regent’s Park into the surrounding countryside (1811-1832), Frederick Law Olmsted’s Riverside (1869) in Chicago, W.H. Lever’s Port Sunlight (begun 1888) in Britain (named after a brand of soap), the Los Angeles garden suburb of Beverly Hills (1906), and on and on.

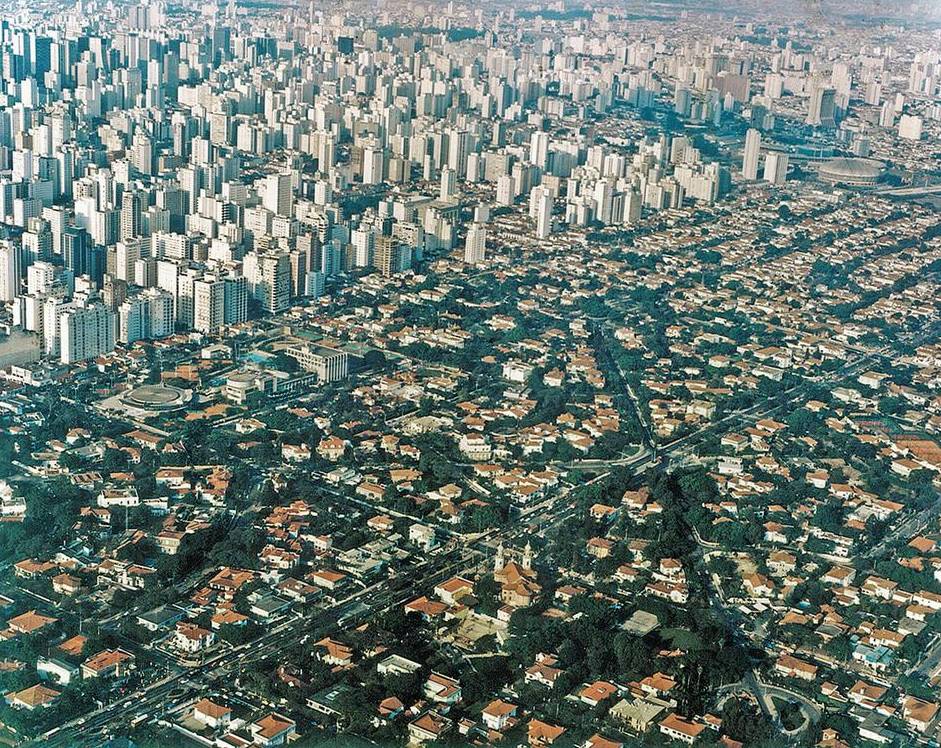

Though the roots of Mr. Stern’s own creative thinking clearly lie in the Anglo-American tradition so well and transparently delineated in this volume, the authors cast their nets very far, scooping up finds in every European country, in Brazil and Mexico and, of course, across the lands of Britain’s empire. Toronto’s Rosedale, Wychwood Park and Leaside are among several Canadian destinations that get paragraphs.

The last project listed in this vast survey is Celebration. At last count, 7,427 people lived there. About 100,000 newcomers arrive in Toronto every year. While the information in this book is useful and occasionally fascinating, and while Mr. Stern argues well for the garden suburb as medicine for ailing cities, I am not convinced that it, or much else in new urbanism’s tool kit, is robust enough to make a positive difference in the lives of the thousands who are coming our way.