If you drop by WORKshop these days, you can catch a wonderful short film about the house of the future, as was envisaged circa 1957. The trim, young housewife in this Cold War vision glides effortlessly among efficient appliances and ultramodern furnishings, while her equally trim, young husband shaves with the latest electric razor. The couple’s adorable daughter frolics through the streamlined open-plan interior of the house, which is shaped like a flying saucer. It is, or was, the American dream.

Such was the meaning of “smart” residential architecture and design upward of 60 years ago. So what is “smart” now? The word is popular and buzzy, but vague. How, exactly, will a “smart” dwelling of the near future appear, perform, behave itself?

Last summer, Larry Wayne Richards, WORKshop’s creative director, invited students in Ontario’s architecture, engineering and environmental science programs to come up with answers to these questions. The competition, called House 2020 – you read about it here in August – attracted 22 proposals, from which a four-person jury last week picked three front-running entries.

All 22 will be on public view at WORKshop (the design studio and store is on the subway level at 80 Bloor St. W.) until the end of January.

If the prognostications of the contestants turn out to be correct, the house of tomorrow will look much like the house of today – or, for that matter, yesterday.

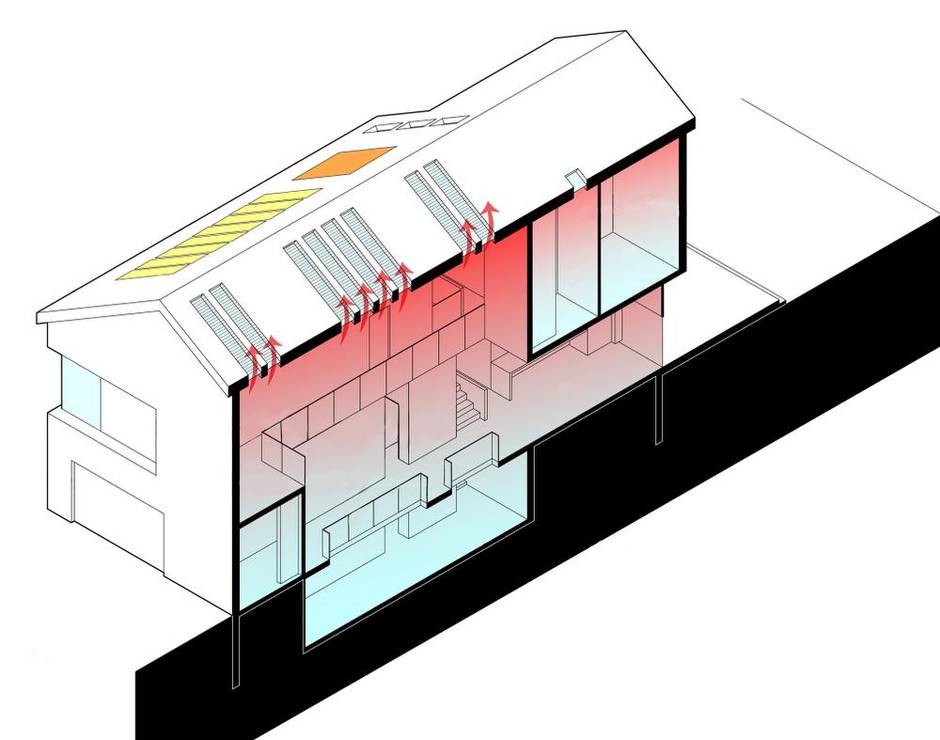

There will be solar panels for heating and geothermal systems for cooling, devices for recycling rainwater, effective insulation, high-performance glazing, extensive prefabrication – technologies and techniques, that is, already with us and not futuristic at all. Cybernetic automation will play no greater part in our lives and lifestyles than it does already. No bold innovations in construction methods and materials are on the horizon. What we can expect are many homes like Red Roof House, one of projects featured here, with its pitched roof, thick insulation, granny suite – and without a thing to cause anyone to take a second look.

Look at the 1957 film again: The house of the future is optimistic, ambitious, forward-looking. The prevailing mood of the 2014 show is resignation to the present-day regime of codes and city planners and the tried-and-true practices of the home-building industry.

But the scarcity of futuristic pizzazz in these projects may be saying nothing about the imaginative capacities of the students.

The competition brief, after all, stipulated that the submitted design must be “realizable, pragmatic, and cost-effective,” and buildable just six years from now.

It also said the structure had to fit on a normal-sized, rectangular subdivision lot in southern Ontario. More than any other aspect of the contest, I suspect, these demands for prompt, suburban doability checked what might have been really bold and original thinking by the students.

That said, 22 individuals or teams from across the province threw themselves into the making (on a tight deadline) of these sometimes interesting proposals, however cramped they may have felt while doing so. Not everyone obeyed the regulations.

Infill House, which won an honourable mention, is a 300-square-foot, prefab, readily portable, $50,000 unit that no public authority would allow anywhere near suburbia. Motion House, which won nothing, is not a house at all, but rather a plea for walkable neighbourhoods.

Each finalist in this round in the House 2020 process – the jury will rank the three in a second judging, later this year or early in the next – has played the game according to the rules. The one who coloured most carefully within the lines is Peter Kitchen. His low-tech adaptation of a plain Ontario tract house, with white walls and double-height spaces and good cross-ventilation, promises to perform better than a developer-built residence. Considered artistically, however, it doesn’t make the heart sing.

The jagged geometry of Plus House, by Christopher Tron and Javier Huerta-Juarez, on the other hand, is memorable. It is based on the gridded layout of the building’s most conspicuous structural elements, seven rammed-earth piers shaped, in plan, like Greek crosses. The scheme is simple, but not simplistic, and, although the proposed dwelling is not large, it has firm authority.

If Plus House is toughly material and local, Nabia Majeed’s Internet of Space floats in the invisible ocean of information we swim in. Unusually in this competition, her house subtly subverts the typical suburban residential format with strong programming. The studio, the reading room, the 3-D printing pantry are purpose-built and outfitted for their roles. They aren’t merely what happens to unused bedrooms. Even the driveway is “smart.”

For the record, all the finalists in House 2020 are graduate students in the University of Toronto’s architecture school. The jurors – who did not know the identities and affiliations of the contestants when they did their work – were U of T professors Ted Kesik and Carol Moukheiber as well as Colin Ripley, architecture chair at Ryerson University, and the Hong Kong-based developer and fashion entrepreneur Kin Yeung, who founded WORKshop and is funding the competition.