The row houses are yellow and salmon, beige and cream, studded with air conditioners and decorative tiles. In photographs, this street in the Portuguese town of Setubal does not look like a site of architectural innovation. It looks like home.

And that is the point of a provocative exhibition now on display at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal. In Setubal and at 170 other sites across Portugal, the great dream of modern architecture – housing for the people – came to life. In only 26 months, Portugal’s revolutionary government produced new housing for more than 40,000 families, through a model that put ordinary citizens in charge of planning their own dwellings. In Setubal, for example, the architect Goncalo Byrne designed those houses and nearby buildings for 420 families, working directly with the people who would live there.

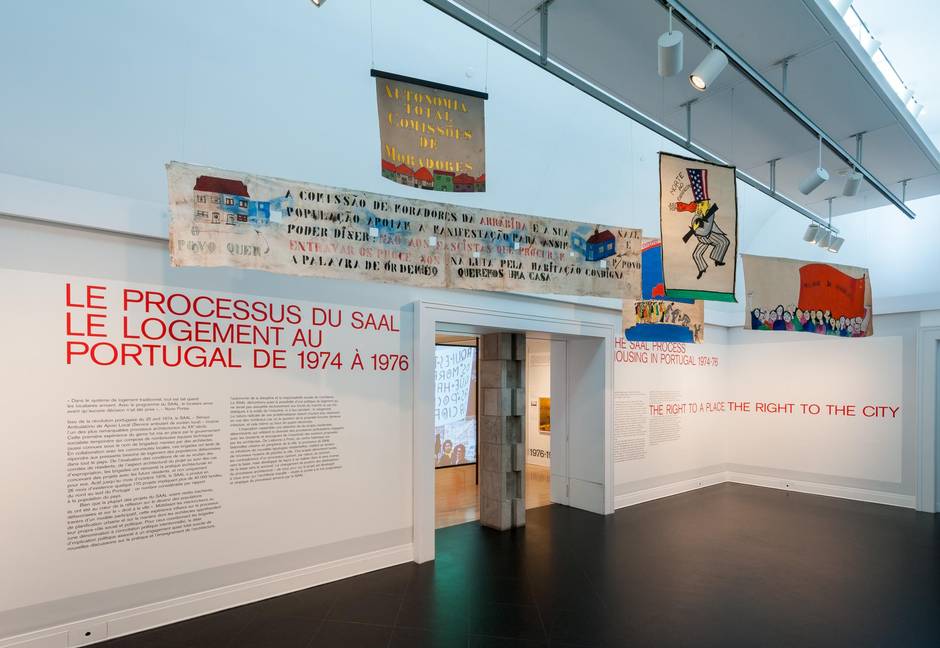

The Local Ambulatory Support Service – SAAL, in its Portuguese acronym – was chaotic, short-lived, and remarkably effective. The CCA show, The SAAL Process: Housing in Portugal 1974-76, asks how this idealistic effort managed to transform so many lives, and what we could learn from its art of the possible.

The exhibition captures the fervour of the period, after the 1974 Carnation Revolution – a nearly bloodless coup that ended 40 years of authoritarian rule. Portugal was a relatively poor and highly unequal society; 25 per cent of the population lived in substandard housing. In this context, making architecture was a deeply political act. “Housing projects, and the related social movements, became synonymous with the new political project of democratization,” says Eszter Steierhoffer, Curator, Contemporary Architecture at the CCA. A battle cry of the period: Houses yes, shacks no! A hand-painted banner from a local SAAL unit depicts an icon of a house: in the middle, a rainbow-clad crowd of youth is kicking a figure in top hat and tails right out of the building.

The reality of SAAL was only slightly less chaotic. The program invited residents in underprivileged neighbourhoods to ask for aid in building housing; the government guaranteed the construction financing and oversaw administration; “brigades” of architects and other professionals went to work for the residents. It became “an experimental, participatory model of building,” Steierhoffer explains, “in which the local residents of the neighbourhoods worked closely with the architects on the planning process.”

Today, many architects are trying to engage in precisely this kind of socially engaged, consultative work. This show is an interesting result of the CCA’s engagement with other global institutions; curated by the Portuguese scholar Delfim Sardo and produced in partnership with Porto’s Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art, it gives us a look at a now-obscure experiment that is deeply relevant.

The CCA’s version of the show adds some context for Canadians about the period in Portuguese history – and while the English-language texts are dense and somewhat unclear, there are enough ephemera, photographs and planning documents to evoke two years of smoky, passionate contention. A documentary film from 2014 revisits a SAAL project in Porto 40 years later; a crowd of aging residents and three of the architects, all long past their revolutionary days, look back on the experience of with deep pride in their communities and, unmistakably, their country.

The show also unpacks the architecture of 10 particular projects through drawings, historic and contemporary photographs, and models. In Porto, the SAAL projects were focused in the ilhas – slums – in the central city and nearby districts. Most of this work is modest in size and character: dense new houses that preserve the crowded scale and intimate social connections of the neighbourhood. In Lisbon, the results were mid-rise apartments in marginal areas of the city – which look more like the social housing produced by top-down models in Britain or, indeed, in Canada.

Some of the housing – including Byrne’s project in Setubal, which occupies steep hillsides with great finesse – is intriguing purely in its own terms. This was a group of idealistic young architects, among them the future Pritzker Prize winner Alvaro Siza, working to integrate historic street and building patterns with more stripped-down modernist forms – and also to respect the fact that the ilhas were “real communities,” as Siza wrote, “organized, dense and teeming with a very particular lifestyle.” These were the right questions and the right answers, informed by listening to citizens. Jane Jacobs would have been pleased.

Many architects and critics of the time were; the more ambitious of the SAAL projects were widely published in international journals. This was work that did real social good, without tripping over ideology or being choked by bureaucracy. This was especially welcome in the mid-1970s, rekindling the fading old avant-garde faith that architecture in the 20th century could, and should, make life better for the many.

In Portugal, it disappeared quickly: The government killed the SAAL program in 1976, and many of the most ambitious schemes were left incomplete or unbuilt.

We need that idealism back. The innovation and passion of architects helped drive the grand building projects of the 1950s and 1960s – including Canada’s centennial wave of schools, universities, hospitals and what used to be called social housing. The government of Canada withdrew funding for the latter more than 20 years ago, and the problem of affordability is serious and growing: According to a report from the Mowat Centre, a non-partisan think tank, one in seven Canadians cannot afford “decent housing.”

Who will invent the social, economic and spatial tools that will allow us to bridge that gap? A better, more equal world, if it comes, will come one house at a time.

The SAAL Process: Housing in Portugal 1974-76 continues to Oct. 4. (cca.qc.ca)