“Best before June 2013!” The tube of knockoff Pringles I was holding had expired more than a year ago. I turned to my partner in hopes of some advice on the purchase I feared I might soon regret, but she just shrugged and passed the young girl some yuan in exchange for our supply of bottled water and expired snacks. Stepping out onto the street and into the 35 C sun, we left the multipurpose store – a wondrous mix of groceries, car parts and live fish – and looked around at the few dust-covered buildings in the small village of Zhuangdaokou. This part of China, we realized, is seldom visited by Chinese travellers – let alone foreign ones. We had finally escaped the throngs of people.

Our next goal: to spend some private time with one of the most famous landmarks in the world. Attracting more than 10 million visitors a year, the Great Wall of China is the country’s second most popular tourist site (after the Forbidden City).

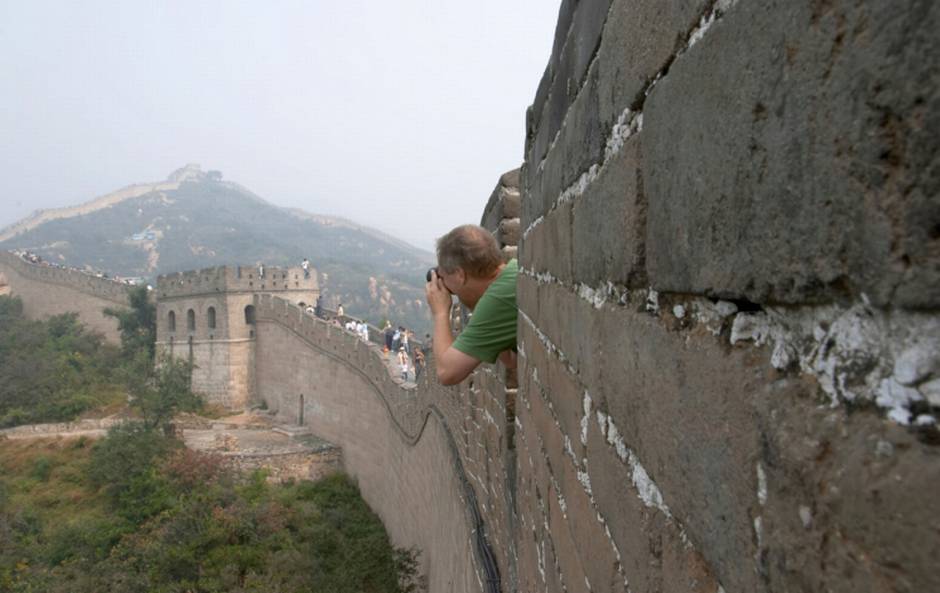

The Badaling section, located about 80 kilometres northwest of Beijing, draws the most sightseers. There, railings support visitors, hawkers harass travellers and the summer crowds can make a person feel as though he is front-row centre at an outdoor festival. After spending a week in the capital – amidst 14 million other people – we wanted to experience the Wall on our own, without guides speaking through loud megaphones or people shuffling for the best photography spots. And although it took some time and effort – speaking with locals through a translator, checking online forums and a lot of guess work – the final reward was marvellous. After a couple scenic hours of public transportation – a train around Beijing, then two buses – we arrived at the small, sleepy village of Zhuangdaokou, located about 100 kilometres north of the city. From there, we followed a dirt hill path through cornfields before coming face to face with the Great Wall.

I had been impressed by countless photos of the Wall before, but seeing it up close – towering over us – brought a new sense of astonishment. From east to west, it stretched up and over the horizon, snaking along the hilltops. I was struck by the sheer immensity of the structure. It was hard to imagine all 8,850 kilometres – built by bare hands – stretching from the Korean border to the Gobi Desert.

The Wall was originally built in small sections to keep out northern nomadic tribes. Later, after uniting the six states of China, Emperor Qin Shi Huang ordered all the segments to be connected. The Great Wall of China, as we know it today, was finished in 220 BC. Over the past 2,000 years it has deteriorated through natural causes – with a bit of help along the way.

In the 1950s, Mao Zedong encouraged farmers to destroy the Wall and reuse materials to build homes. In 1984, areas started to be restored. Later, as the droves of tourists began arriving, additions such as guardrails, shops and even a cable car were added.

The section between Zhuangdaokou and the neighbouring village of Huanghuacheng is also fully restored, but without any of the modern extras. That did make things trickier: At times, the Wall was so steep we had to climb using all fours to prevent from falling backward. (I couldn’t help but wonder whether the Chinese soldiers used it as a toboggan run in winter months.)

As the sweat poured down our faces in the sweltering afternoon sun, we crested an extremely steep hill. I was exhausted and slightly dehydrated – but the beauty of the wild landscape surrounding Beijing immediately blew me away. The view was breathtaking: lush valleys to the east and a massive lake and water reserve to the west, with mountains for as far as the eye could see. But the best part? Experiencing it in silence. This was the change we needed after six days in Beijing – a small slice of the beauty this complicated country has to offer.

At the top of the hill we came across the first guard tower of our journey. Each one was a sanctuary from the blistering heat that tried to cook our delicate, wintered, Newfoundland skin. Inside many of them, we found blackened wood and remnants of plastic bottles – signs of overnight camps from the few trekkers before us. Camping on the Wall is a finable offence, but many foreigners take the risk for the chance at bragging rights.

After three hours of hiking, we climbed down to the village of Huanghuacheng. The townspeople greeted us with a wave and a “Nin hao,” but were not aggressive in their selling tactics; they left it up to us to approach them if we needed anything. Communicating through hand gestures with one woman, we deciphered that a bus to Beijing would be arriving in about 30 minutes. At a small stall we bought ice cream and water, sat down and, once again, stared up at the Wall in all its glory. I began to speculate the number of man hours that went into building this wonder, and the number of lives lost in its construction.

“Bus! Bus!”

The shouts of the woman yelling at us pulled me out of my thoughts. We sprinted across the road and flagged the bus down, which came to a halt with a gut-wrenching screech. We boarded feeling excited and refreshed, but still hungry. I popped open the tube of “Pringles” and threw one in my mouth. I spit it out immediately, much to the curious disgust of my partner and other passengers.

“I think they went bad.”

IF YOU GO

The Wall originally started in small sections to keep out the northern nomadic tribes. Later, after uniting the six states of China, Emperor Qin Shi Huang ordered all the sections to be connected. Thus he created the Great Wall of China.

Getting there

Taxi: You can take a taxi to Zhuangdaokou or Huanghuacheng for around $75-$100.

Public Transport: From the main Great Wall access hub station of Dongzhimen (located on Line 2 of the subway), take the 916 bus to Huairou ($2, 1 hour). Upon arrival, walk two blocks (50 metres) to the next bus stop and catch the one headed to Shui Changcheng ($1, 1.5 hours). Tell the attendant you want to get off at Zhuangdaokou; they’ll let you know when to get off.

Caution: While in Huairou, people will approach you and ask where you are headed. If you tell them Zhuangdaokou, they will say there is no bus but that they can take you in mini-van for a fee. Pay no attention to them.

Where to stay

You’ll find small, low-budget hotels in Zhuangdaokou and Huanghuacheng, but it’s better to stay anywhere in Beijing and see the Wall as a day trip. The Hilton Beijing Wangfujing (from $150 a night) is close to the Forbidden City and close to the subway for easy mobility.

What to do

Once at the Wall, just follow it from one village to the next. You don’t need a guide, just some food, lots of water (especially in the summer months) and a sense of adventure. The hike takes two to three hours, which allows lots of time for breaks and photos.