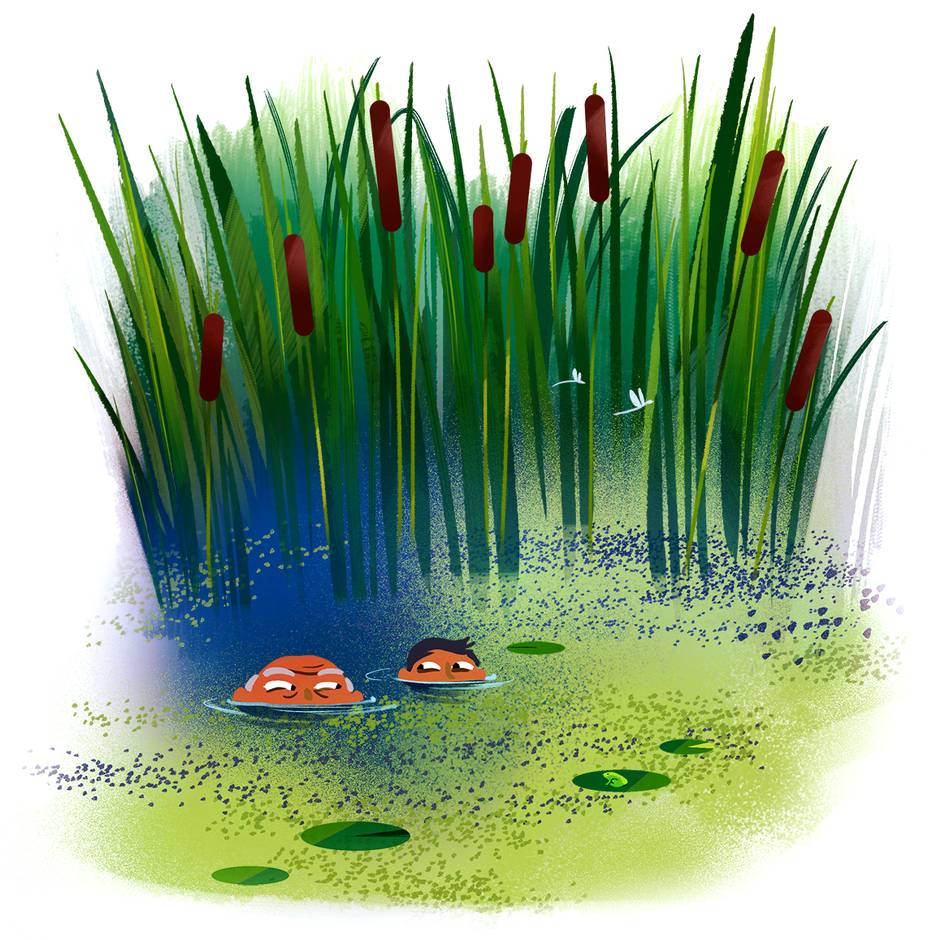

I am 72. Oliver is 8. We are swimming in pond scum, looking for frogs and stuff.

That’s right – pond scum. The technical definition for pond scum describes filamentous algae that form mats on the surface of a pond. The algae apparently begin their lives at the bottom of the pond and, buoyed by the oxygen bubbles they produce, ooze to the surface producing a greenish, mottled coating on the water.

Oliver and I wriggle our shoulders through the slime and cattails and lily pads, then hunker down like crocodiles waiting for our prey: amphibians, fish or insects. We welcome all.

Oliver has a catching gift. This summer, he went under a dock and emerged with the biggest bass any of us had ever seen. No hooks, gaffs or spears involved: just a quick-handed little boy, a landing net and that huge fish, which he flipped back in the water after showing it off to a slack-jawed assembly of his kin.

That was on a lake, of course, not this scummy pond on Oliver’s aunt and uncle’s farm in hill country near Peterborough, Ont. No bass here. But frogs. Oliver catches them with casual regularity, cups them gently in his hands, and then – as always – sends them on their way.

This boy is nothing if not inquisitive. Eventually the questioning gets to why we are wallowing in a fetid swamp when, about 100 metres away, his aunt and uncle have a bright blue swimming pool.

“Grandpa,” Oliver asks earnestly, “is it true that people think swamps are disgusting?”

I ponder and give it my best shot. “People who like their lives neat and predictable undoubtedly don’t feel all that comfortable in a swamp,” I reply. “But you are clearly a boy who likes both nature and surprises. So that’s probably why you have dragged me in here – for the second year in a row – while the others are splashing around in the swimming pool.”

Oliver smiles and says nothing.

Later, at the farmhouse, we talk about water and how it has brought our family together, from the wombs that all of us swam in once, to old age. I tell him that I used to voyage forth with his mother and her brother when his mother was 9 and her brother was 8.

We had a favourite lake. We sailed on it, skipped stones on it, dived in it, fished from it, threw grandma into it and watched the sun set over it.

But the best thing we did was turn ourselves into porpoises once we were in it. I was the Head Porpoise back in those days. Oliver’s mother and her brother were the babies, and grandma – then in her early 30s – chose to remain a human on shore.

The baby porpoises used all the strokes they had been taught. The breaststroke was clearly superior for looking around. The backstroke always seemed as though it was going to be wonderful for thinking, but serenity almost always gave way to a gnawing uncertainty about direction. The sidestroke was heavenly. But they suffered from doubts that it was really very useful for anything more than resting up and chatting. The crawl was useless for conversation, but quite satisfactory for pondering and dynamite for stretching into a torpedo and thrusting ahead, if only to remind the lake who was in charge. The butterfly, they all agreed, was for showing off.

Once, they swam to an island with their mother alongside in her motorboat. But while it was good to have her along, everyone knew that having the boat there was wrong.

The next day they left their mother at the dock with binoculars. Once, the waves got too big and she came roaring out in the boat, sputtering that the Head Porpoise was an irresponsible fool of a father.

The farthest they got, two days before going back to school, was the very last island – halfway to town. Their mother brought her boat over and they ate tuna fish sandwiches, lying on their stomachs.

When their ancestors had emerged from the sea, they wondered, had they been in a hurry to get on with evolution? Or did they first lie out on sun-drenched rocks, drinking in the rays?

On Labour Day they got up early – not to swim far, they agreed, but to say goodbye to the lake. A fine mist hung over it. It didn’t seem like summer any more. Still, the lake had just enough warmth left to offer up a welcome.

Off the point, they were surprised to see a flock of mergansers. Quietly, oh so smoothly, they swam over and joined them. So close, they would say later, that they could almost count feathers.

The next summer, sister and brother were no longer porpoises but remained best friends. They built a fort, water-skied and talked about getting married some day. Which they did, and had kids: Eva and Sabine for him; Oliver and Georgia for her.

“The kid named Oliver … he turned out to be more of a crocodile than a porpoise,” observed the self-same Oliver, after the story was over.

“That he did.”

“Grandpa, which do you like better, lakes or swamps?”

“Both good,” said I. “Both are way better than a swimming pool, wouldn’t you say?”

“I would say,” said the gentlest crocodile you’re ever going to meet. “Especially the swamps. Not neat. But very, very cool.”

Dan Turner lives in Ottawa.