Each month, Sebastian Cyr uses a specialized extraction device he describes as being "as simple as a toaster," to make a concoction that he says relieves his Lyme disease symptoms.

The Montreal resident dumps two cups of coconut oil into a contraption marketed as the Magical Butter Machine, along with 15 grams of cannabis, which he gets delivered through the mail from one of Canada's two dozen licensed commercial growers.

"Out of that, I crank out 250 capsules," says Mr. Cyr, who takes four of these pills three times a day. The pills don't get him high, but they help him deal with the spasticity in his back and his limbs.

Federally regulated medical marijuana producers started producing and selling oils after a Supreme Court of Canada decision last year, but patients complain it's expensive and supplies often run low or sell out. And even then, only a handful are producing the particular varieties that Mr. Cyr says help him. Buying the raw buds and making his own capsules is at least half the cost of purchasing the producers' cannabis oil.

These are all problems the nation's hemp growers – which until now have been limited to selling seeds and fibre for consumer products – say they can easily solve, and their federal trade association is pressing Health Canada to let them break into the medical market.

Hemp is marijuana's taller, skinnier cousin. While bearing the same unmistakable odour of pot, all hemp grown in Canada must have only trace amounts of the tetrahydrocannabinol compound, or THC, found in marijuana that gets people high. Instead, most hemp is rich in cannabidiol, or CBD, which emerging research suggests is effective in treating epilepsy and a range of other ailments. These high-CBD products are increasingly appealing to families with children who suffer frequent seizures.

Male and female hemp plants at Jim Rogers hemp field near Cochin, Sask.

David Stobbe/For the Globe and Mail

Mr. Cyr makes his capsules from marijuana strains that have been bred to contain high levels of CBD and low levels of THC. But hemp growers say there are thousands of acres of farmland in Western Canada that could produce similar strains to what Mr. Cyr uses in his capsules. Hemp farmers say they can do this much cheaper than the licensed marijuana growers, in large part because they don't need the Fort Knox-style security required of those growers to prevent theft or diversion to the black market.

"It's an absolute waste of a crop that has significant potential," says Kim Shukla, executive director of the Canadian Hemp Trade Alliance.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of tonnes of hemp is legally grown across the Prairies and harvested for seeds and fibre before the rest of the crop – the flowers, bracts and leaves – are threshed into chaff and left to decompose.

The seeds are often exported as hemp hearts or ground up into flour, both trumpeted for high levels of unsaturated or "good" fat and protein, respectively. The fibre can be harvested for rope or clothing, but only about 10 per cent of the Canadian crop is used commercially because the country's textile manufacturing sector is not large enough.

Though this hemp must contain less than 0.03 per cent THC, it can have much higher concentrations of CBD, which Health Canada also classifies as a controlled substance that may only be produced by those licensed in its mail-order medical marijuana system.

Since 2009, Ms. Shukla's trade association has asked the federal government to update its hemp regulations, which were adopted in 1998 when, she says, CBD had already been lumped in with cannabis and its other derivatives as dangerous substances.

Canada is now the world's largest exporter of industrial hemp – mostly for food products destined for the United States – and could be shipping $142-million worth of products by 2020, she said.

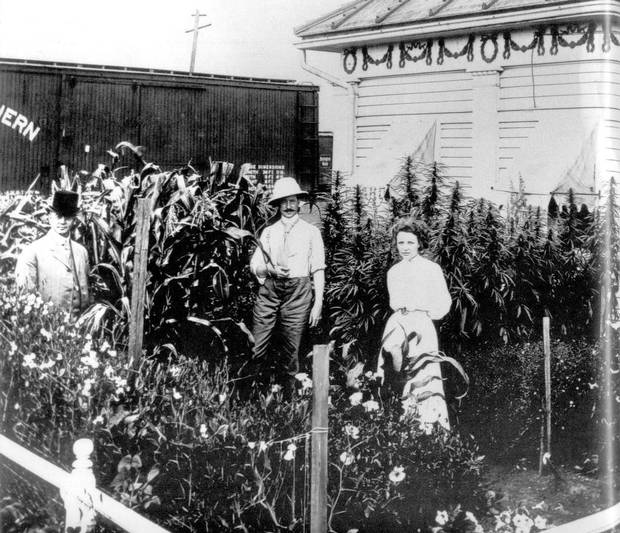

Hemp was grown throughout Western Canada by European settlers before it was outlawed along with marijuana in 1938. This 1909 photo shows Saskatoon Mayor William Hopkins (left) standing with Board of Trade commissioner F. Maclure Sclanders and an unidentified woman in front of a demonstration garden that includes hemp.

Saskatoon Public Library

But that market could suffer as the U.S. hemp industry grows; it is currently just a tenth the size of its Canadian counterpart. More than half of the states have legalized industrial hemp farming, though only the stalks may be used to make commercial products. Since the stalk does not contain much of the sought-after CBD compound, U.S. companies must import their high-CBD oils from European hemp producers if they want to make medicinal products legally.

Hemp startup Phivida Organics Inc. is based in Vancouver, but is restricted to selling its high-CBD-oil-infused foods across the United States because the compound is still illegal in Canada unless it is produced under Ottawa's commercial medical marijuana system.

"We'd love to be able to offer this to Canadian families as a Canadian company," says president John-David Belfontaine.

Mr. Belfontaine is also the president of another company waiting for Health Canada to approve its application, filed in 2013, to grow medical marijuana at a facility in Squamish, B.C., so it can sell high-CBD products to Canadians.

For now, he says Phivida will focus on their U.S. business while hoping legislation expected next year to legalize recreational marijuana will open up the market for CBD-based medical products in Canada.

Ms. Shukla says that is a no-brainer as Canadian hemp companies have proven over the past two decades that their flour and seed products are safe for consumer products. Her trade group has also been asking Health Canada to drop the onerous testing requirements that prove the THC levels in their crops remain below 0.3 per cent.

To date, their lobbying has fallen on the deaf ears of a government that thinks "we're not important enough," Ms. Shukla said.

"We're kind of an odd bird; we're a different fit [for Health Canada]," she said.

Jim Rogers poses for a picture in his hemp field near Cochin, Sask.

David Stobbe/For the Globe and Mail

The federal agency refused to say whether it has any plans to grant the industry's wishes, with spokesman André Gagnon noting it continues to engage with Ms. Shukla's association and other stakeholders "to inform a balanced and evidence-based approach to controlled drugs and substances."

Two summers ago, Jim Rogers, a lifelong wheat and canola farmer from Saskatchewan, told The Globe he was excited to cash in on the new crop after getting licensed by Health Canada.

None of his other crops has ever generated such a buzz from neighbours.

"It's entertainment; people want to see it," Mr. Rogers said. "Generally the reaction has been positive. People are just curious."

But, that interest didn't translate into good business. Recently, he said he had given up his foray with the plant after two harvests because a supply glut at the country's biggest wholesaler has allowed him to sell just a quarter of all the hemp he has grown.

Asked if he would consider growing hemp again to make CBD-rich pills and oils instead of trying to sell it as a food product, Mr. Rogers said: "It's a lot of regulation to do that. I wouldn't really want to go any further."