Desperate measures

who uses water — and what they should be doing to save it

Wendy Stueck and Allan Maki report

Sandra Oldfield is a former Californian and part-owner of Tinhorn Creek, a winery about five kilometres south of Oliver in a desert-like strip of B.C.’s Okanagan Valley.

She is familiar with drought and what it can mean for businesses such as hers that rely on irrigation to cultivate the grapes that have become an economic mainstay in the region. This week, as many British Columbia learned of fresh limits on when they could water their lawns or wash their cars, Ms. Oldfield suggested people might consider getting used to it.

“Welcome to the rest of the world, B.C., the world that has known water restrictions for many, many years,” Ms. Oldfield said Wednesday on Twitter.

With a drought gripping much of Western Canada, homeowners, business operators and politicians are taking a hard look at water consumption, some for the first time. While bans on lawn-sprinkling tend to be the first prong of drought response plans, there is an increasing emphasis on making better use of the resource.

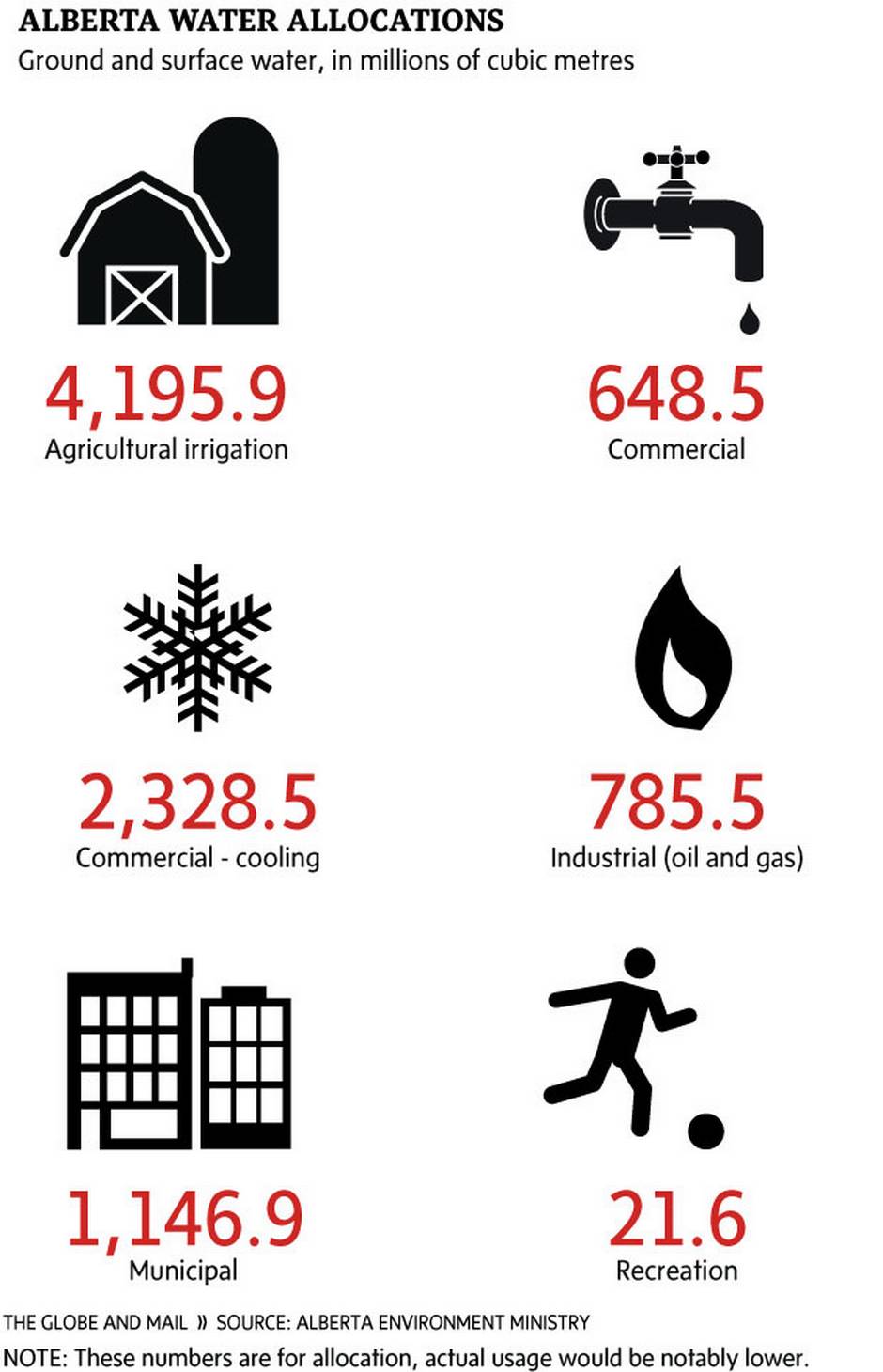

The current water shortage is also drawing attention to water-intensive industries, including agriculture, Alberta’s oil sands and B.C.’s potential liquified natural gas sector. And it has renewed debate over B.C.’s arrangements with bottled-water giant Nestlé Waters Canada. The company extracts groundwater from an aquifer near Hope for free, but under new legislation that takes effect next year, will be charged a fee of $2.25 per million litres of water to access the water – a price many maintain is not high enough.

Such concerns are global. In January, for the first time in a decade of such reports, water crises topped a list of global risks, in terms of impact, compiled by the World Economic Forum. (Interstate conflict topped the list in terms of likelihood.)

So far, Tinhorn Creek has not yet faced drought-related difficulties, other than having to use more water to counter hot, dry conditions. Even so, Ms. Oldfield is looking for ways to conserve. Over the past four years, the winery has converted from sprinkling to drip irrigation, reducing its consumption by about 70 per cent.

“Before we were watering the whole canopy and the grass between the rows,” Ms. Oldfield says. “Now we’re just watering the grapes.”

The notion of using water judiciously features prominently in local governments’ conservation campaigns. The Okanagan Basin Water Board, which co-ordinates water use among the three regional districts that span the Okanagan Valley, urged residents this week to conserve water, warning failure to do so could result in “mining” of Okanagan Lake.

The prospect – extracting more water than what would be restored next spring – could threaten everything from nearby orchards to the floating bridge that links Kelowna to communities on the west side of Okanagan Lake.

“We have never mined the lake,” said board executive director Anna Warwick Sears. “All of our infrastructure, our whole community, is built around the assumption that the lake will be operated within this 1.5-metre range,” she said, referring to the average amount by which the lake refills each year.

In the Okanagan, the driest part of Canada, agriculture accounts for about 55 per cent of water use. Outdoor residential use – mostly lawns – accounts for 24 per cent.

While urban residents can stop washing their cars and sprinkling their lawns, ranchers can’t stop feeding their cows.

Alberta has received less than 40 per cent of the normal rainfall compared with a year ago, and hay is selling for up to $150 a bale – double its typical cost.

Former NHL defenceman Dean Kennedy is a cattle rancher in Pincher Creek. While he was fortunate to produce enough hay to feed his Angus cattle now and put aside some feed for the winter, other ranchers are already tapping winter supplies.

Rancher Dan Pahl is doing everything he can to keep from selling off some of his herd, including moving cattle from one grazing spot to another to allow grass to recover and drawing some water from the South Saskatchewan River. (Those withdrawals are monitored by the province.)

“We’re trying to be good stewards of everything,” Mr. Pahl said. “But if we don’t get any rain next spring, it’s doing to be a disaster.”

The drought’s ripple effects are being felt by multiple and diverse industries, including beer producers, with business owners finding ways to adapt before they’re forced to.

On B.C.’s Sunshine Coast, near Gibsons, Persephone Brewing Co. has reduced the amount of water used to make craft beer through better measurement and some new equipment, says general manager Dion Whyte. It takes Persephone about three litres of water to produce one litre of beer, lower than an industry standard that is closer to four litres.

Reducing water use is part of being a good corporate citizen and will come in handy if water supplies tighten in the future, Mr. Whyte said. The brewery has a grassed event area, but is using brewery waste water to irrigate it.

Municipalities, too, are looking at a host of ways to reduce water consumption.

In Alberta, Okotoks has reduced its per capita water consumption to less than 285 litres a day with a program that includes consumption-based utility rates and door-to-door education campaigns. (In Ontario, Waterloo in 2011 installed a system that collects runoff from two artificial-turf fields to irrigate four fields with natural turf, saving about 10 million litres of drinkable water that otherwise would have been used for irrigation.)

Hans Schreier, professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia and an instructor in watershed management, would like to see more jurisdictions use water meters, saying they typically result in a 30-per-cent drop in consumption once they are installed.

According to a 2014 Statistics Canada bulletin on residential water use, 58 per cent of Canadian households were equipped with water meters in 2011, compared with 52 per cent in 1991. Over the same period, average daily water use dropped 27 per cent, to 251 litres in 2011, from 342 litres per person in 1991.

Despite the downward trend, Canadians remain big water users by global standards, using 1,420 cubic metres per capita a year. Only Americans, at 1,730 cubic metres per capita, use more, according to the OECD.

Residential water use accounts for less than half – about 43 per cent – of water distributed by municipalities, the Statscan bulletin said.

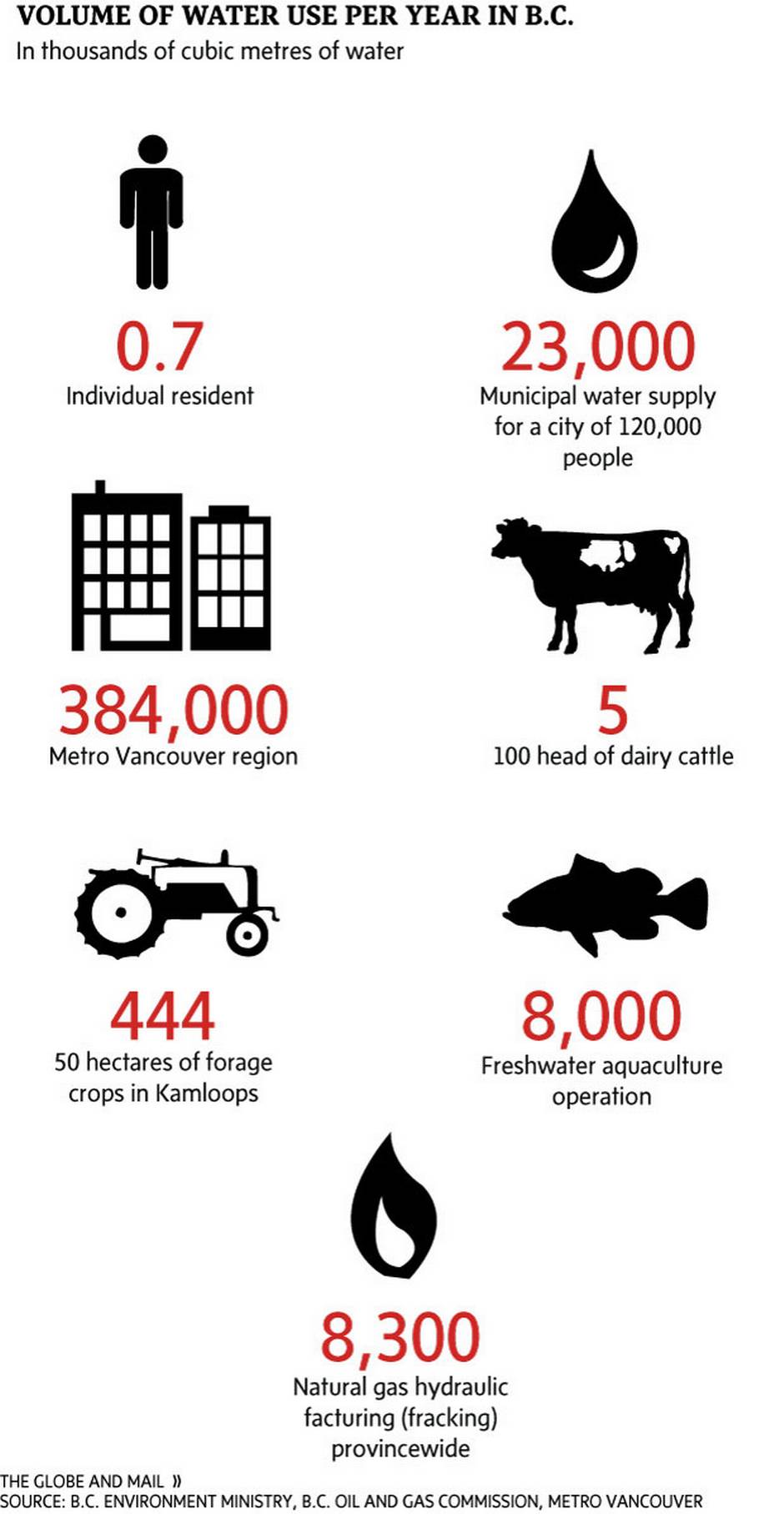

Metro Vancouver - comprising about 2.4-million people in the Lower Mainland - used about 384 million cubic metres of water last year.

In Calgary, a city report says residents withdrew 176.4 million cubic metres of water last year, a decrease of two million cubic metres from the year before. The city says the average single family in Calgary uses 220 litres per person ever day.

Epcor, which runs the local water system for greater Edmonton, says the region used about 126.5 million cubic metres of water in 2014 – or about 195 litres per person every day.

In B.C., a new water sustainability act is scheduled to take effect next year. The legislation will include new rental rates for industrial users and, for the first time, regulate and apply fees to groundwater. Those fees are currently under review following a public outcry related to Nestlé.