When it was first approved in 2008, Grouse Mountain’s Eye of the Wind attraction was hailed as “Vancouver’s first commercially viable wind turbine,” capable of powering 400 homes or generating as much as 25 per cent of the energy needed to run the year-round tourist destination.

The energy minister at the time touted it as “a highly visible icon,” but, as one researcher noted, the blades rarely turn on the relatively windless peak. Grouse spokeswoman Jacqueline Blackwell couldn’t say how much energy the turbine produces, noting the challenges and limitations of the project were fully understood before it was built, but added that it is a “compelling educational tool” that has shown more than 200,000 visitors “the potential application of alternative energy sources.”

There is no industrywide framework among British Columbia’s and Alberta’s ski resorts to co-ordinate such advocacy for a fossil-fuel-free future or prepare for global warming.

In the past decade, B.C.’s South Coast has gotten a glimpse of warm and wet ski seasons that experts say could be the norm in 35 years if worst-case emissions scenarios hold true. This season, a moderate El Nino system has soaked skiers and kept snowpacks very low on Vancouver’s three North Shore mountains and the much-higher slopes of Whistler Blackcomb. Ski areas further inland near the Rockies have more snow, but many still have bases below their historic averages for this time of year.

Over the past 50 years throughout most of B.C. and Alberta, the average nightly low temperature in the middle of winter has increased at least 2 C near the coast and up to 5 C in parts of the Rockies, according to University of Saskatchewan hydrologist John Pomeroy. Dr. Pomeroy, a Canada Research Chair in Water Resources and Climate Change, said climate change has shortened the spring ski season anywhere from four to six weeks at many hills.

“It’s going to be the edge seasons – the fall and the spring – and the lower elevations and the sites that were already marginal that will be first affected,” Dr. Pomeroy said. “The ski areas I’ve seen that are already in trouble … are the ones that are already adapting to it – they’re really good at snowmaking.

David Lynn, president and CEO of the Canada West Ski Areas Association (CWSAA), representing 136 ski areas across Western Canada, said each resort is tackling the problem in its own way. Mr. Lynn pointed to Grouse’s turbine and Whistler Blackcomb’s hydroelectric dam as leading examples of the ways resorts are lowering greenhouse-gas emissions.

“Ethically, it’s the right thing to do,” Mr. Lynn said. “But secondly, we don’t want to be contributing to a problem that’s going to have adverse long-term impacts on our own industry.”

But the association has no program to encourage and publicize these solutions, as in the United States where the National Ski Areas Association started a program 14 years ago to give technical support and recognition to ski resorts that monitor, reduce and measure their emissions.

Last year, 30 U.S. resorts voluntarily set measurable annual targets for reducing their emissions through methods such as switching to LED lighting, installing solar panels, increasing composting and buying more efficient snow-making machines. Over the past two years, the company that owns Aspen’s four mountains has teamed up with Protect Our Winters – a non-profit group of famous winter sports athletes concerned about climate-change issues – to lobby politicians in Washington to pass laws supporting clean energy.

Arthur De Jong, Whistler Blackcomb’s head of sustainability and mountain planning, said the Canadian industry’s lack of cohesive action mirrors society’s general inability to grapple with such a global problem. “There’s a business imperative and a moral imperative,” said Mr. De Jong, who added his resort saves a million dollars annually by switching to renewable energy.

Mr. De Jong said many of B.C.’s resorts are implementing their own “grassroots” clean-energy initiatives, but he added: “We have to work harder collectively, keeping in mind Whistler is, by far, the largest operator with the greatest depth of infrastructure and capacity so our job is to pull, our job is to show leadership.”

Operators such as Whistler Blackcomb are adapting to global warming by carving out slopes at higher elevations. No one today would build as low as 850 metres, where West Vancouver’s long-defunct Hollyburn Chairlift – which opened in 1951 and burned down in 1965 – sits in ruins. If it operated now, its slopes would receive about a quarter less snow per year, according to the climate modelling done by Michael Pidwirny.

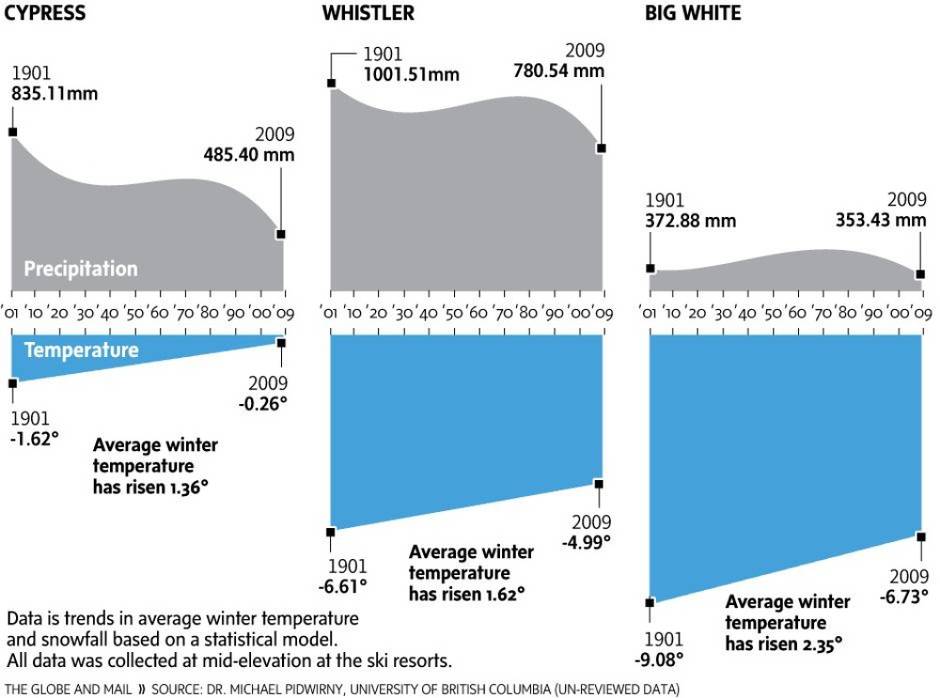

Prof. Pidwirny, a physical geography professor at the University of B.C.’s Okanagan campus, says above it, Cypress Mountain isn’t doing much better, as the “one bad year in 10” it experienced 50 years ago has now increased to about three bad years each decade. “The number of bad years is increasing so probably by 2050 maybe five or six of the years that occur in the decade would be bad years,” said Prof. Pidwirny, whose research uses data from UBC Forestry’s ClimateBC program to calculate the historic snowfall at B.C.’s ski resorts and predict how they would be affected by a warmer climate, as modeled on various global emissions scenarios.

Percent change in snowfall

A model of future forecasts at three major B.C. ski resorts

SOURCE: Dr. Michael Pidwirny, UBC

Prof. Pidwirny was asked to present his research at the April CWSAA conference and hopes to get funding to establish permanent weather stations ski hills across B.C. to validate what his models are forecasting. “I’m trying to explain to them how knowing about the future is important for decision making,” he said.

Dr. Pomeroy said the ski industry has a leadership role to play: Ski culture has always set fashion and lifestyle trends, and mountains could be a catalyst for greater societal change through educating their “very influential” patronsin a friendly manner. “What’s going to matter is when they go home, are they working for the oil industry? Are they working for the coal industry? Can they take it back to the boardrooms and say, ‘Hey, we’ve got to improve the efficiency of these things or start to look at alternative sources.’ If they’re driving out there in their big SUV and going home to a big house, well maybe they have to think about that a bit.”