Those who commit heinous crimes often find themselves behind bars, in some cases for life. But what exactly is that life like?

Before the famed Kingston Penitentiary closed a year ago, award-winning photographer Geoffrey James was granted access to create a visual record of life inside an institution that opened for business 32 years before Canada became a nation. For six months, he visited regularly, spending two or three days at a time and constantly being surprised, especially by the sheer complexity of the place. Walking through KP’s massive door into the leafy streets of Kingston gave Mr. James ‘an inkling of what it must feel like to be caught between two irreconcilable worlds.’ It’s an inkling he now can share. These images are from Inside Kingston (1835–2013) Penitentiary by Geoffrey James (Black Dog Publishing) as well as an exhibition on display at Queen’s University’s Samuel J. Zacks and Contemporary Feature Galleries until December 7th.

This exercise yard, replete with pink lawn chairs, was built as part of a proposal to house women at KP (it was never used).

Left: Bars that had been screened to provide some privacy (not officially allowed). Right: A cell decorated with a Harley Davidson logo and paintings of marijuana leaves.

Cells decorated with a full-press paint job (not a common practice) and a pin-up girl and the words "Go Leafs Go!"

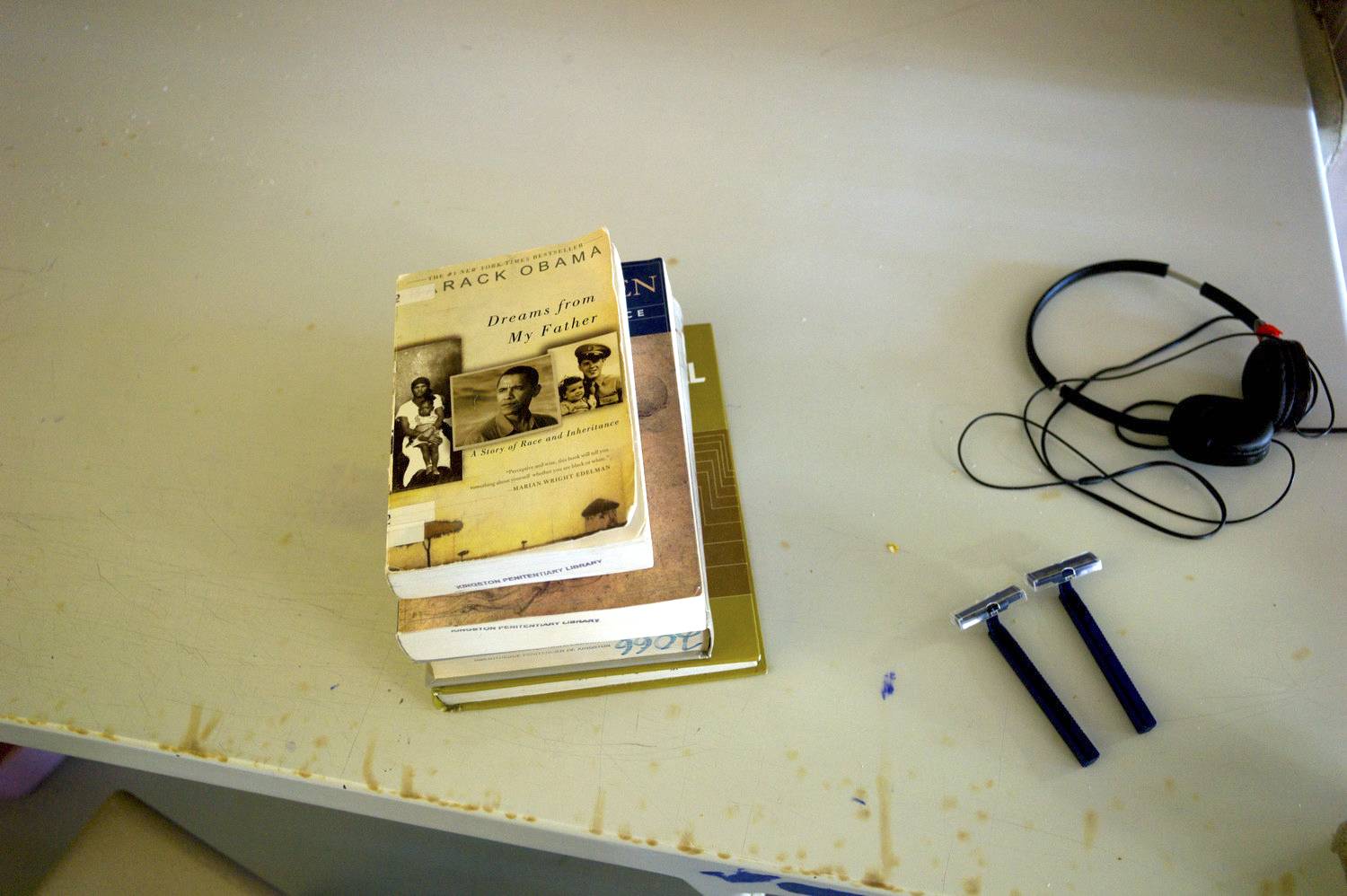

Inmate reading material included Barack Obama's autobiography.

A cell mural by an inmate from Nunavut.

The mural depicting loons on the water was the work of an inmate who'd been behind bars since 1987. "Sometimes," he wrote on the wall (borrowing from a self-help guru), "when I consider what tremendous consequences come from small things, I am tempted to think there are no small things."

The shadow board made it easy to spot if a tool was missing.

The visitors' room is where friends and family had to surrender their wallets and cell phones, be checked for drugs (by a sniffer dog) and bear in mind that 'hugging or massaging are prohibited behaviours.'

The family-visit housing units were built in keeping with the penitentiary's late Georgian period architecture and each had at least two bedrooms. Normally, offenders were allowed a visit (up to 72 hours) every two months. Food could be ordered, and toys were provided for children (they weren't allowed to bring their own).