Jason Kenney said the government won't touch it. Joe Oliver says he might. Stephen Harper never liked it in the first place.

Suddenly the federal contingency reserve – an obscure accounting entry with a rocky and highly-charged political history – is at the heart of the debate around the 2015 budget.

The Globe and Mail takes a closer look at the evolving history of the contingency, its various forms and how it could be a key factor in whether the Conservative government can forecast a balanced budget.

The rationale

The federal government is a massive enterprise. Last year it spent $276.8-billion. It took in $271.7-billion dollars. The shortfall between those amounts – $5.2-billion – is the deficit. The Conservative government is promising to get the revenue side out in front of the spending figure, which would erase the deficit and return Ottawa to surplus.

Even in good economic times, trying to get those two large amounts to line up is a major forecasting and management challenge.

To account for that uncertainty, the government deliberately low balls its revenue projection by $3-billion a year. Officially known as an “adjustment for risk” but often referred to as the contingency fund or reserve, it gives the government room to handle unforeseen events. It is essentially an accounting move. The money is not placed in a separate account.

What can it be used for?

The point of the contingency is to cover unforeseen events. Finance Minister Joe Oliver has stated that falling oil prices meet that definition. Employment Minister Jason Kenney muddied the waters recently by suggesting the contingency fund would not be touched.

“We won’t be using a contingency fund. A contingency fund is there for unforeseen circumstances like natural disasters,” Mr. Kenney told Global’s The West Block, in an interview that aired Jan. 18, just days after Mr. Oliver announced he would delay the release of the 2015 federal budget until at least April.

The government would not comment on the issue for several days after, but Mr. Oliver has recently struck a different tone.

“I am not precluding the use of the contingency fund,” Mr. Oliver told reporters on Jan. 26, the day the House of Commons resumed sitting. “That is something that the budget will reveal… The contingency fund is there for unexpected and unavoidable events of which a precipitous decline in oil prices is. So we may or may not need to use the contingency fund. But, if we do, it will be entirely consistent with government policy.”

The Mulroney years

While the 2014 budget was a 419-page document, until the early 1980s, budgets weren’t much more than a speech and short document of about 50 pages.

A 1973 Globe and Mail story makes reference to an increase in the “contingency fund” through a spending estimates vote. The Tory budget of 1985 – under prime minister Brian Mulroney – makes reference to a “contingency reserve” but does not specify the size. The 1990 budget appears to be the first clear reference to a budgeted contingency reserve, describing a $3-billion contingency “to manage foreign exchange transaction.” Federal budgets going back as far as 1968 can be found on Finance Canada’s website.

The Chrétien/Martin years

The first two budgets under Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien marked the first time a contingency reserve was clearly identified and explained. The reserve was set at $3-billion a year and would go toward reducing the size of the deficit if it was not required.

As the government moved from deficit to surplus in the 1997-98 fiscal year, the practice was maintained with unused contingencies going toward reducing the debt. Over time, Liberal budgets began to add additional contingencies, described as prudence. Generally this would be worth $1-billion for the year ahead and grow by $1-billion for each additional year into the forecast.

This prudence was briefly eliminated and the contingency was scaled back in the December 2001 budget in response to economic conditions and the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attack. That budget eliminated the prudence fund and reduced the contingency to $2-billion. The move allowed the government to avoid showing a deficit. A similar adjustment was made in a 2003 fiscal update.

The reserve and the prudence fund were later restored in the 2003 budget. The reserve and prudence funds were maintained under prime minister Paul Martin, the former finance minister who was prime minister from Dec. 2003 until his defeat in the 2006 federal election.

"The government continues to hide large surpluses and then blow them in end of year bonanzas, and the budget continues exactly this kind of practice," said Mr. Harper, then Official Opposition leader, in his response to the 2004 Liberal budget. "There is a better way. That better way is to return some of these massive surpluses to Canadians and their families in the form of tax reductions."

The Harper years

In 2006, the first Conservative budget under Prime Minister Stephen Harper did away with the notion of a contingency reserve and prudence adjustment. The Conservatives viewed the contingency and prudence funds as a Liberal trick to hide the true size of expected surpluses.

“Since the federal deficit was eliminated in 1997-98, budget surpluses have frequently been higher than projected. This has eroded the credibility of the budget process and limited the scope for parliamentarians and Canadians to debate alternative uses of surplus funds. A new approach is required,” the budget stated. “The former practice of adjusting the budget projections for economic prudence is discontinued.”

An annual $3-billion entry was added for “debt reduction,” which was similar to a contingency reserve in that unused contingencies go toward the debt. No additional prudence was included. That practice continued for the first three Conservative budgets under finance minister Jim Flaherty. But the government’s 2009 budget – delivered on Jan. 27, 2009 in response to the economic crisis – brought back a form of contingency under a new name. Called the “adjustment for risk,” the 2009 budget added a cushion of $800-million that year, followed by $4.5-billion for the year ahead and $3-billion the following year.

The 2010 budget continued the focus on stimulus spending and made no reference to an adjustment for risk. The 2011 budget explained that the government’s forecasts include $1.5-billion downward adjustment of revenue for risk for each of the next two years to reflect the “remaining uncertainties surrounding the global economic outlook.” Smaller adjustments were made to the three outer years in the government’s five-year forecast.

With its first budget written by a majority Conservative government, the 2012 budget outlined a $3-billion a year “adjustment for risk” for each of the next five years. This practice was repeated in the 2013 budget and the 2014 budget.

What now? Can low oil still be an unexpected event in the 2015 budget?

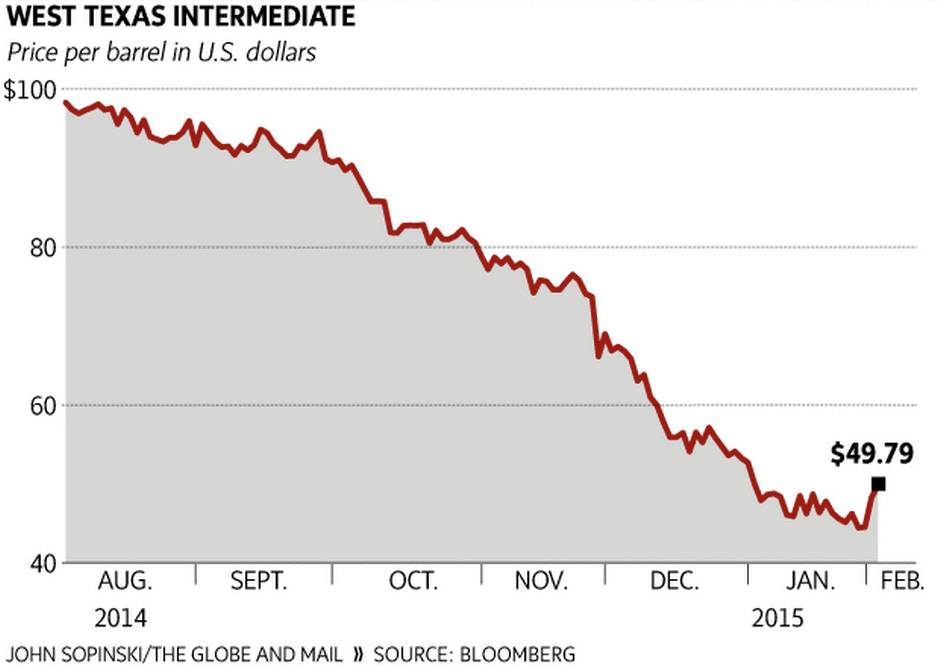

The finance minister’s comment that he is “not precluding” the use of the contingency fund to show a balanced budget raises new questions about the government’s plans. The minister’s fiscal update included $3-billion a year in its forecasts for contingencies. But if that money is used to address the impact of low oil prices, it is unclear whether the government would put an additional $3-billion aside to cover unforeseen events like the natural disaster example cited by Mr. Kenney. The Parliamentary Budget Officer released a report on Jan. 27 that assumes the contingency fund will essentially disappear in the 2015 budget. If the fund is maintained, the PBO numbers indicate it would be harder for the Conservatives to show balanced budgets in the coming years.

Assuming oil stays at $48 (U.S.) a barrel, the PBO said Ottawa is facing a $400-million deficit in 2015-16, followed by a $2.5-billion surplus the next year. If the contingency is maintained, Ottawa would instead be facing a $3.4-billion deficit in 2015-16 and a $500-million deficit in 2016-17.

Bank of Montreal chief economist Doug Porter – who is of the view that Ottawa’s finances are on track for either a small surplus or deficit even with a $3-billion contingency – said now is not the time to shrink or do away with the contingency reserve.

“I think $3-billion is a very reasonable amount to set aside for uncertainty. I don’t think it’s excessive by any means, but I also don’t think it’s too small,” he said. Nonetheless, Mr. Porter repeated the widely-held view of economists that a small deficit or a small surplus is of little real consequence to the economy.

“I don’t think we should be agonizing over a billion dollars,” he said.

With additional research by Rick Cash. Produced by Chris Hannay.