Canada's election laws are set to change. A major government bill, the Fair Elections Act, is working its way through the House of Commons but has proven controversial. It's a big deal, so here's your crash course.

This page will stay updated as news develops. Submit your own questions by e-mail or Twitter.

- What is the Fair Elections Act?

- Who's behind it?

- What are the changes?

- How's it going over?

- Why is it a big deal?

- What's the government's argument?

- What's The Globe's view?

- Has the bill passed yet?

- I have another question...

What is the Fair Elections Act?

Who's behind it?

What are the changes?

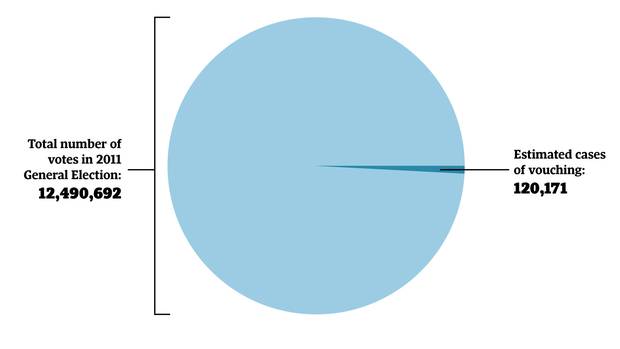

1. Vouching

The chief electoral officer of Ontario, which doesn’t have vouching but does allows use of the voter card, has said it’s best to have one if not the other.

This proved to be a lightning rod for controversy, and is one of the areas where the Conservatives (kind of) backed down. They’ll still axe vouching but will introduce an oath system instead – a voter who has ID, but can’t prove a current address, can sign an oath to where to they live. If another valid voter signs a second oath, essentially backing up the first voter’s address, the first voter is given a ballot. The NDP and Liberals supported the amendment, but more because it restored at least something – they warn people could still be turned away on voting day.

2. Campaign finance

3. The Chief Electoral Officer

The head of Elections Canada is targeted, but outcry led the Tories to back off the wording a bit. The bill nonetheless limits what the Chief Electoral Officer can say, or “provide to the public,” – a gag order, critics say.

Government emphatically rejects that, but the bill still limits the Chief Electoral Officer’s powers, if not his personal freedom of speech. The bill limits what advertisements the Chief Electoral Officer and Elections Canada can run – ads saying where, when and how to vote will be OK, but ads actually encouraging people to vote will not.

It’s not just ads being limited. Several observers warned Elections Canada programming aimed at boosting civic literacy would also be cut, because it’s not within the bill’s new, strict mandate for the CEO. The government responded with an amendment guaranteeing programs aimed at primary and secondary school students, such as Student Vote, can continue; it does not make the same guarantee for adults.

So, in short, the Chief Electoral Officer can still say what he wants, but his agency now is having its hand forced when it comes to ads and programs. It’ll mean no ads from Elections Canada encouraging people – or groups with particularly low voter turnout – to cast a ballot. And it will apparently spell the end to some civic literacy initiatives, which critics pan as short-sighted at a time of low voter turnout.

Under the bill, the CEO will now be appointed to a single 10-year term. Until now, a CEO has, once appointed, been eligible to serve until age 65. The current CEO, Marc Mayrand, still will be, and is therefore due to retire in 2018.

4. The Commissioner of Canada Elections

Essentially the elections cop, the commissioner investigates people for shady campaigning, though has been criticized as ineffective by watchdogs. The bill will move the commissioner out of Elections Canada and into the officer of the Director of Public Prosecutions. The current commissioner, Yves Côté, said the move is “not a step in the right direction," he said, adding he had "deep concern" with a proposal to limit what he could say publicly. Mr. Côté also reiterated his previous calls for the power to compel testimony in investigations – a power the bill did not include, despite the requests. (The director is among many who say he was not consulted about the change.)

A government amendment guarantees the CEO can still share any document or information, obtained lawfully, with the commissioner, in response to complaints to the committee that the commissioner’s relocation raised privacy concerns.

Former chief electoral officer Jean-Pierre Kingsley said the change is a neutral one, because of a previous change that already requires the DPP to be involved. “To me, it’s ballgame over on that one and the [latest] change really isn’t affecting anything,” he said.

The bill creates new offences – for impersonating a candidate or elections officials, for instance – and hikes fines for those found guilty.

5. Data of who voted

6. Permission to hire

7. Poll clerks

The bill will allow local party associations – or, failing that, national parties themselves – to nominate deputy returning officers and poll clerks. (Currently, people for these positions can be nominated by the parties’ local candidates.) These are people who help oversee the vote at your local polling station. The Chief Electoral Officer warns the provision has no “operation benefit” and that waiting for nominations may not leave enough time to recruit and train proper officials.

In addition to expanding the list of people who can appoint those roles, the bill initially proposed to add in a whole new partisan appointment process. It suggested the party that won the most votes in a previous election be able to recommend people to act as central poll supervisor, a person in charge of a particular polling location. This was among the bill’s most contentious proposals and was widely criticized. The government backed down, and voted down its clauses. Political parties will not be able to recommend people to work as central poll supervisors.

8. Donation limits

9. Robocalls

10. Third-party advertising

Outside groups are currently allowed $200,100 in ad spending during an election campaign period. Under the bill, they’ll now be allowed that for anything in “relation” to an election – not just during the campaign itself. This could dramatically reduce the amount groups can spend on political advertising, because the sum outside groups could spend in a campaign – as little as 36 days – would now be applied, theoretically, to a period of four years. However, the bill’s critics are divided on what impact this provision will have.

Political parties, meanwhile, face no limits on what they can spend on advertising before an election period formally begins.

This all sounds big. How's it going over?

Not well. Mr. Kingsley, the former chief electoral officer, initially gave it a grade of A-, but the response from academics and observers has otherwise largely ranged from concern to flat-out opposition. The Tories tried to push the act quickly through the House of Commons. The NDP tried to force cross-country tours for the committee considering the bill, which was rejected. The NDP have since done their own.

It all led the Conservatives to announce amendments on April 25, backing down on some of the bill’s provisions. Those changes include compromise on the elimination of vouching by allowing electors to sign an oath attesting to their residency, though they must still show proper ID; rewriting the provision that restricted what the chief electoral officer could say; removing a provision to exempt some kinds of fundraising; keeping records in a new robocalls registry for three years, instead of one; and changing the language around the hiring of central poll supervisors. The NDP say about two-thirds of the problems in the bill persist, however.

So why is it a big deal?

Aside from the fact that the bill was rewriting the rules for elections, it had a lot of critics. They include a group of Canadian academics and a group of international ones. Canadian student groups have objected to the elimination of vouching and other changes. The international scholars, in particular, warn the bill will not only dilute the strength of Canada’s democracy, but set a poor example for fledgling democracies worldwide.

What do regular Canadians think?

Early polls suggest that the more people know about it, the less they like it (see this one from February and this one from March). An Angus Reid poll in April, for instance, found 52 per cent of those who weren’t familiar with the bill liked it, while only 41 per cent of those who were familiar with it liked it. The polls also suggest that, while few Canadians knew about the legislation at first, more are slowly hearing about it. Another poll in April, from Ipsos Reid, found only 23 per cent of Canadians were following the debate "closely" and 70 per cent were fine with the elimination of vouching.

What's going on in the Senate?

The Senate had been asked to “pre-study” the bill while it was still in the House of Commons. It produced a report unanimously recommending nine changes to the bill, though the bill hadn’t yet formally been sent to the Senate – an unusual situation. The government accepted some of the Senate’s recommended changes, such as doing away with the fundraising loophole and increasing the time robocall records must be met, though not all. However, a Senator on the committee has already said she’d expect the amended bill to pass the Senate without further changes. The amended version of the bill is now before the Senate.

When would this take effect?

Some of it would kick in as soon as it’s passed, and certainly before the next election, expected in late 2015. The government hopes to pass it by June.

What's the government's argument?

What's The Globe's position?

You know, Mr. Poilievre’s right. I really like this idea. What should I do?

You could tell your MP. Find him or her here.

I don't like this bill. What should I do?

Has the bill passed yet?

I have another question...

E-mail us or tweet at us.

This explainer is written and produced by Josh Wingrove, Chris Hannay, Matt Frehner and Matt Bambach.