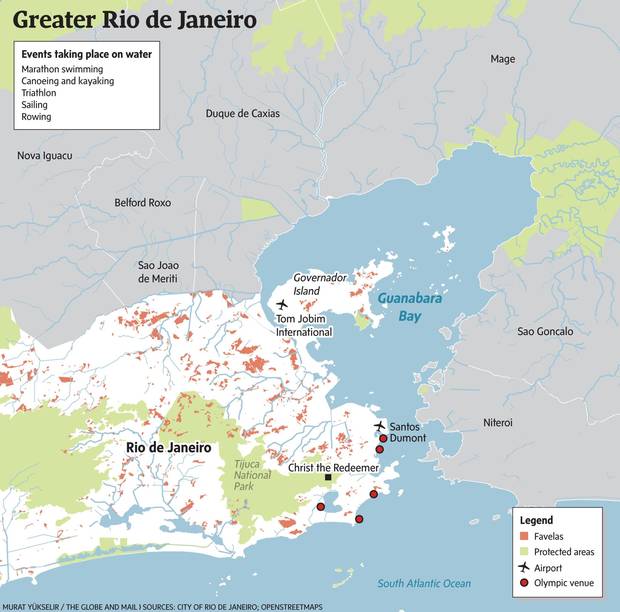

When the team bidding to bring the 2016 Summer Games to Rio de Janeiro made their pitch back in 2009, they showed the International Olympic Committee pictures of sailboats on a glassy harbour below a cradle of mountains, and swimmers plunging into turquoise surf off Copacabana Beach.

And they admitted that while the pictures were lovely, the water was rather less so. A couple of hundred years of dumping raw sewage and industrial effluent has destroyed the mangrove system that once filtered the bay, filled the harbour with sludge, killed off most of the dolphins and many other species, and left the water a toxic mess.

But the Olympics, the bidders said – the Olympics, with its sailing and swimming and rowing events – would be the catalyst Rio has needed to finally clean up its water. The Olympic bid promised that by the time of the Games, Rio would have 80 per cent of its sewage treated.

Today, with the Games just a month away? It's 21 per cent.

There are plans to take some emergency measures for the duration of the Olympics themselves: Barriers are being installed over the biggest canals, to catch larger solid items, and a flotilla of small boats will churn across the bay to scoop up the old couches, stray shoes and plastic bags and bottles that litter its surface. But when the athletes and tourists leave town, residents of Rio are going to be back to living with open sewage in their neighbourhoods, a choking stench around the bay and beaches that threaten serious illness for anyone who hasn't developed immunities.

So what happened? Why is Rio's water so foul, and why didn't it get any better?

The first problem was with the promise

So says Livia Cunto, who researches Rio's water for an advocacy organization called Casa Fluminense, and who has an encyclopedic knowledge of both the plethora of actors and the graveyard of failed efforts to fix the pollution.

The basic math is this: The pledge to get to 80 per cent was based on the assumption the city was already at 56 per cent. But the 56 figure came from a national household survey which asked people if they had sewage collection – and most of those who said yes, explains Ms. Cunto, meant that they had a pipe that took the water away when they flushed the toilet. They didn't mean – or know, or, in many cases, particularly care (we'll get to that) – whether that water went to a sewage treatment plant or out to a storm drain and right into the sea.

The figure for people whose sewage was actually treated back when the bid was made was 15 per cent. So to get to 80? "That was mad," Ms. Cunto says.

Garbage is seen on Sao Bento beach.

Daniel Ramalho/for The Globe and Mail

But why is the water so bad?

Rio's water starts in the forests or comes through the Paraiba River system; some of it arrives already tainted with sewage from cities further up the system (lack of sanitation is a national problem). All told, 55 rivers drain into the hydrological basin around Guanabara Bay. And two things pollute it before it hits the sea – industrial effluent and sewage. Rio hosts a busy port, a giant oil-refinery complex and petrochemical and pharmaceutical industries that send runoff containing heavy metals into the bay, says Carla Ramoa Chaves, a geographer who sits on a special commission for Guanabara Bay at the Rio state congress. It is monitored and controlled under environmental legislation, although monitoring budgets (like everything else) have been slashed in Brazil's economic crisis.

Eloisa Torres, who oversaw public policy for the state sanitation and environmental project for Guanabara Bay for seven years until this past April, says the industrial pollution situation is not great, but a system exists to control and improve it. The sanitation problem, on the other hand, is a mess. Sewage goes from houses into canals, then ditches and storm drains, and into the rivers. "Rio's rivers are effectively the sewage collection system now," Ms. Chaves says. Along the way, the waste water picks up trash from all the areas that lack proper waste disposal. Fecal coliform levels in the bay are thousands of times above those registered as safe.

The Alegria ETE Station (centre) was opened in 2009 to treat polluted waters.

Daniel Ramalho/for The Globe and Mail

Why is it so hard to fix?

Rio has had an action plan to fix its sanitation crisis, of one kind or another, underway since 1996, when the Inter-American Development Bank and the Japanese government put up more than 1 billion real ($393-million) to get the city connected to sewage treatment. That plan missed its first deadline, and four extensions, and was finally considered concluded 20 years later. Four sewage treatment plants were built in 20 years; the last of them just recently became operational. Miles of main collection pipes were laid, but the final phase, with the pipes going from the main lines into streets and up to houses, was never done in many places. A total of 800,000 people were connected in the two decades; meanwhile, the city grew and grew (to a total population of 8.7 million now). The Olympic-inspired plan was supposed to make that final step.

But many things went wrong.

Birds are seen perched on floating garbage on Catalao beach.

Daniel Ramalho/for The Globe and Mail

First, bureaucracy, the enemy of so much progress in Brazil

The sewage going into the bay originates in 16 different municipalities, with different utilities and standards in place in each. A law to create an over-arching municipal body that would have the authority to administer sanitation for the whole region has been stalled for years. Meanwhile, the over-arching water resource policy is federal, and the federal government has traditionally been the funder of major infrastructure even when a project is entirely within a state, as Guanabara is – Brazil's federal government has been in the grip of a political crisis for nearly a year. Building and managing infrastructure, meanwhile, is a state affair. And the state is a mess, too.

An aerial view of The Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca.

Daniel Ramalho/for The Globe and Mail

The political crisis had a direct effect on projects such as this

The Olympic cleanup plan had a number of key components that were kneecapped by Brazil's political crisis and the massive corruption scandal that underpins it. The graft investigation has ensnared every major construction firm in the country, including those that were building new canals and collection networks – and slowed their work considerably. The ensuing political upheaval has toppled politicians and snapped alliances, meaning an already painfully slow approvals and tendering process has been set back, starting from near zero every time a key official changes.

Then there's money

Ms. Cunto has research claiming it would cost 19 billion real to go from what metropolitan Rio has now to full sewage treatment. That's a hefty bill by any standards. Brazil is in the grip of a fierce economic decline – with GDP set to contract by 4 per cent this year, after a 3.8 contraction last year. And the state of Rio, which drew much of its revenue from royalties from the oil fields off the coast of the state, is particularly hard hit, after oil prices collapsed. The state is risking default on its international debt, and is months late paying salaries. The many components of the sanitation program that were late getting started because of bureaucratic snuggles are now completely frozen by the budget crisis.

Residences in the Mare favela next to the Cunha channel throw sewage directly in Guanabara Bay waters.

Daniel Ramalho/for The Globe and Mail

Stinky as it is, treating sewage isn't a political priority

Spending money on sewage is not politically popular, Ms. Torres explains: You have to rip out streets and houses, it's expensive, it's messy and many people don't see the point. Politicians get more political capital from a new school or park – so municipal sewage interventions are most likely to take the form of slapping a cement cover over a ditch, rather than connecting to a filtration system or building a plant.

Much of the untreated sewage comes from the favelas, the slums that creep up Rio's hillsides – informal housing built by slaves after emancipation, and by impoverished immigrants from the north, all of them shut out of the city proper. These communities were built without sanitation, and the state has rarely tried to extend it. The popular perception is that favela residents don't pay taxes, so there is little enthusiasm for spending money there. Many still are not included on official city maps – and so they weren't a target for any municipal services.

And even when there is motivation to try to take sewage collection to the favelas, it's still really hard to do.

"There is no public space to deliver services and if the state goes in to do it, it has to take out homes," Ms. Torres explains, quickly sketching out a narrow laneway and showing how devilishly difficult it is to put helter-skelter houses onto a pipe system, or make way for a main collection trunk. The removals for Olympic infrastructure projects have made the issue of forced evictions more politically sensitive and unpopular than ever.

Aerial view of Rio das Pedras favela with The Rio das Pedras (Rocks river) in the middle.

Daniel Ramalho/for The Globe and Mail

And often it's not a personal priority either

There's also a cultural component, Ms. Cunto says, referring to the survey in which people say they "have sanitation" just because their toilet flushes out to the ditch. In Rio's traditionally marginalized communities, accustomed to the near-total absence of the state, there is a lack of understanding about the kind of sanitation people should expect – or of what happens to the water that trickles past, smelling foul.

And in the handful of communities that have had sewage lines brought in, people have been reluctant to pay to connect their homes (a fee of about $85, when minimum wage is $370 a month) because it's costly and they don't trust the state that historically neglected them actually to be treating the water, she added.

And the problem extends beyond favelas: Auditors find rich condominium towers dumping sewage into the storm drains because they don't want to pay to hook up to the grid, Ms. Torres says, and beachfront condominium complexes built with their own small sewage plants frequently just don't run them, because they're expensive and complicated – while dumping into the sea is free.

Will Rio's water ever get better?

If all of the projects underway now are completed without further delay, Ms. Cunto says, then 45 per cent of Rio's sewage will be treated by 2020. Ms. Torres points out that even if the pollution stopped tomorrow, it would take decades to restore the bay ecosystem – for the organic matter on which it's now choking to break down. Ms. Chaves, the geographer, notes that there is much more involved than collecting waste water and trash. "It's much more than just pipes – it's rehabilitation of vegetation and protection of water sources, resuscitating the mangroves, restoring forest cover removed for informal housing," she says.

And yet Ms. Cunto finds a way to be optimistic. "This isn't Canada," she says bluntly. "From where we started, we've come a long way."