Peterborough, in middle England, and Styria, in lower Austria, sit 1,500 kilometres apart on a map of Europe. The former is a fast-growing city a short train ride north of London, the latter a region of laid-back villages set among the vineyard-covered hills near the Slovenian border.

The down-at-heel backstreets of Peterborough would seem to have little in common with the small and neatly maintained villages of Styria. But the people of middle England and lower Austria agree on two major points these days: Things aren't going well where they live – and people from other places are to blame.

That irritation, seized on and moulded by populist politicians offering questionable salves, is on the verge of redrawing the political map of Europe.

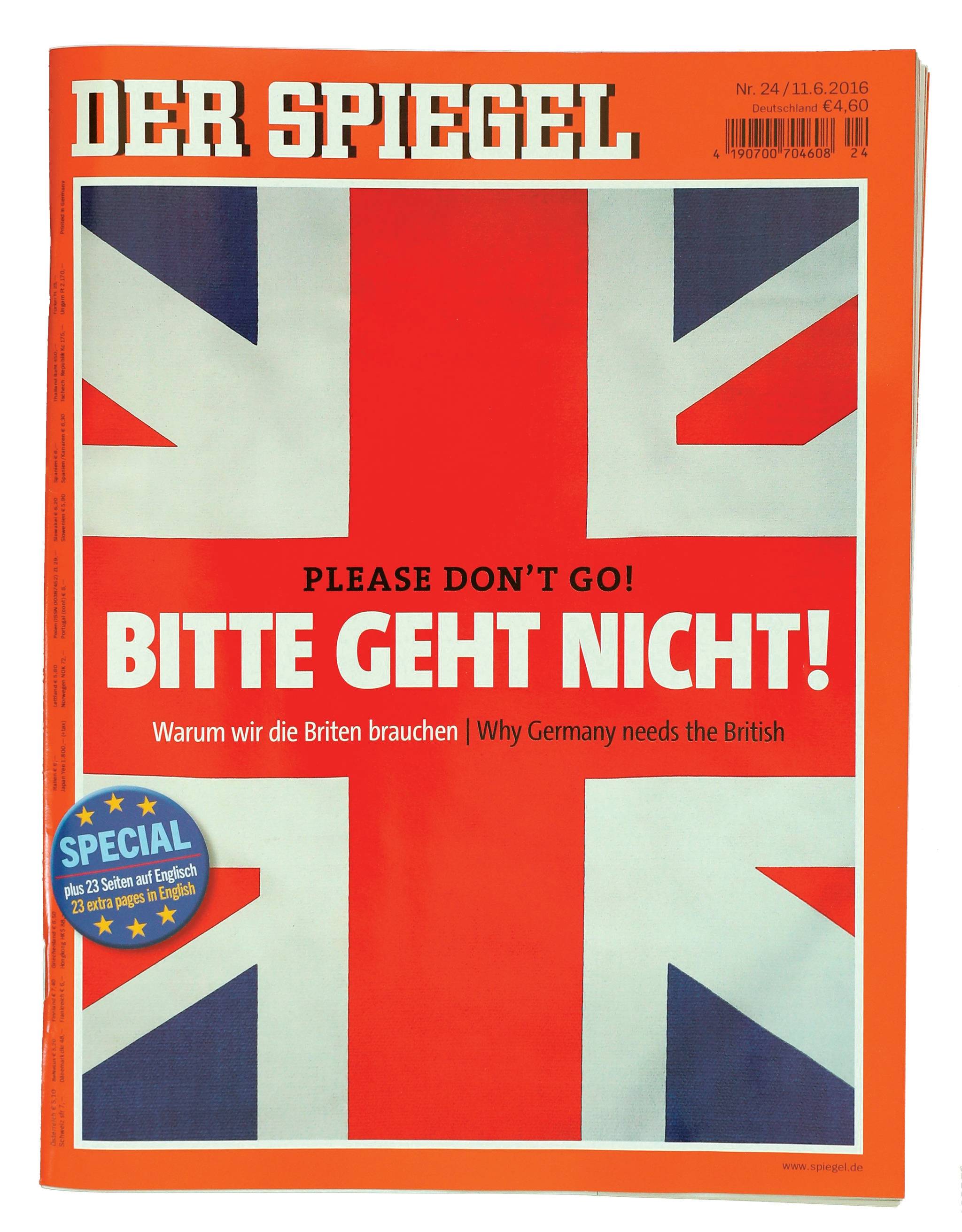

Middle England is the heartland of the Vote Leave campaign as the United Kingdom hurtles toward Thursday's referendum on whether the country should quit the European Union. The pro-EU Remain campaign has accused those pushing for a "Brexit" of being motivated by xenophobia.

The bitter argument seemed to tip into violence this week when Jo Cox, a Labour MP and outspoken Remain supporter, was shot and killed by a gunman who reportedly shouted "Britain first" before the attack. It was an event that some attributed to the increasingly sour and divided atmosphere that the referendum has created.

"When you present politics as a matter of life and death, as a question of national survival, don't be surprised if someone takes you at your word," wrote Alex Massie, of The Spectator magazine, taking aim at the Leave campaign's tactic of whipping up anti-immigrant sentiment. "I cannot recall ever feeling worse about this country and its politics than is the case right now."

Still, a series of recent opinion polls have shown the Leave campaign pulling ahead in the last days before the crucial ballot, as voters apparently coalesce around its easy-to-understand message of "taking back control" of the U.K.'s borders.

"It's a popular movement," Lisa Duffy, an organizer for Vote Leave in Peterborough, says with a smile. She thinks her side will win Thursday's referendum.

Ms. Duffy, who is also a veteran activist in the U.K. Independence Party, a radical right-wing movement better known as UKIP, says a desire to control immigration – something that's near-impossible while Britain is a member of the EU, which considers the free movement of citizens a core principle – is what's driving Vote Leave's surge in the polls. "We want to know who's here, why they're here, and when they're going back, if necessary."

Styria, meanwhile, was an electoral fortress for Norbert Hofer as the Freedom Party candidate came within 31,000 votes last month of becoming Europe's first far-right head of state since the end of the Second World War. Mr. Hofer, who warned against a "Muslim invasion" while campaigning with a Glock pistol on his belt, capitalized on concerns that many of the 90,000 people who arrived and applied for asylum in the country last year aren't integrating well into Austrian society.

"There is a direct connection between the fears of the people and the vote for Mr. Hofer," says Andreas Gerhold, a pastor in the Styrian town of Stainz. "The arguments of Donald Trump are the same as the arguments of the Freedom Party here in Austria."

The Freedom Party – founded 60 years ago by former Nazi officers – is now challenging the presidential election result in court, hoping to force a re-run before the winner, independent left-of-centre candidate Alexander Van der Bellen, is sworn in on July 8. Some Vienna-based analysts think the Freedom Party could indeed force, and win, a new vote; Mr. Hofer had looked on course for victory until postal ballots tipped the result in Mr. Van der Bellen's favour.

The Brexit referendum and the Austrian election drama are likely harbingers of what's to come in other parts of Europe. Across the continent, populist movements that have been kept on the fringes for decades are suddenly closing in on the corridors of power.

In Italy, Virginia Raggi of the Five Star Movement looks set to win a second-round run-off in Rome's mayoral election on Sunday after topping the first ballot by a wide margin earlier this month. Euroskeptic and anti-establishment, Five Star has allied itself with UKIP at the European Parliament.

In France, Marine Le Pen of the far-right Front National has a wide lead in opinion polls ahead of presidential elections next year. Polls in the Netherlands show the country's Party for Freedom, headed by Geert Wilders – who is currently on trial for inciting hatred against the country's Moroccan community – would win an election if one were called today.

Far-right parties are also gaining in opinion polls in Germany and Scandinavia, while governments in Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic have soothed public opinion by vowing to ignore an EU quota system that would see all member countries absorb a share of the more than one million asylum-seekers who arrived on the continent in 2015.

After a decades-long lull during which things like borders and ethnicity seemed to matter less than in the past, angry nationalism is back – no longer as a bit player, but as a mainstream force in European politics.

Fishermen and campaigners for the Leave campaign demonstrate in boats outside the Houses of Parliament in London on June 15, 2016.

Luke MacGregor/Bloomberg

Raw emotions and English flags

To walk south down Peterborough's Lincoln Road is to take a miniature tour of our globalized world. A Turkish bar is followed by a Polish food store, an Afghan grocery by a Latvian café.

It's only when you get closer to the centre of town, where a portrait of the Queen keeps watch over ancient Cathedral Square, that the English flags – not the Union Jack of the United Kingdom – start to appear. White-and-red crosses bulge from T-shirts and hang from windows. So do the similarly coloured Vote Leave stickers encouraging a Brexit. They look like stop signs: "Little England," as the more nationalist-minded regions of this country are somewhat derisively known, pushing back against immigration and cultural changes that many in Peterborough say have gone too far.

One of the first symbols of the backlash you encounter near the south end of Lincoln Road are a pair of English flags sticking out from a table of bric-a-brac in front of a pawn shop.

"On this part of the road, it's necessary to show that you're English," explains Chris, the 69-year-old owner. Despite his desire to make a statement, he asked that his last name not be published, fearing that his business might be affected if his political opinions were made public.

He said he will vote on June 23 in favour of a Brexit, ending more than 20 years of non-participation in politics. It's too late to turn back the clock, and he doesn't want to see the immigrants already here forced to leave, but he says the U.K. needs to start curbing immigration, and soon. "There are lots of people who were born here – or who came here long ago – who like what we have and want it to stay that way."

The June 23 referendum wasn't expected to be this dramatic. That the U.K. should remain in the EU is a rare point on which the leaders of the four biggest political parties – the Conservatives, Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Scottish National Party – all agree.

U.S. President Barack Obama has also weighed in to encourage Britons to vote Remain. So have the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Bank of England's own Mark Carney, all of whom piled on warnings of the economic risks the U.K. would be taking if it chose to leave the 28-nation bloc that is also the world's largest free-trade zone.

But advice and threats from the establishment are ignored in Little England these days. Politicians and economists are the ones who told them the EU – and, more broadly, globalization – would make everyone wealthier.

Earlier this year, the YouGov polling agency identified Peterborough as one of the most pro-Brexit places in the U.K., and campaigners say they expect at least 60 per cent of residents to vote Leave.

Lifelong residents of the city, especially older ones, say they no longer recognize some of the streets they grew up on. And they want the change to stop.

There are indeed parts of this city of 190,000 (up from 156,000 in 2001) where Polish and Russian are almost as common on street signs as English. That's nothing new in such cosmopolitan cities as London, New York and Toronto, but it's not a course Peterborough residents feel they had a hand in setting.

The rapid influx of people drawn to the region's low-skill agricultural and food-packing sectors has also put a strain on social services. "My constituents are in a situation where 68 per cent of primary-school children don't speak English as their first language, school places are at a premium, health services are under huge pressure. Crime and policing is a problem. And housing is at a pressure point," says Stewart Jackson, the Conservative MP for Peterborough, who has gone against his party's leader, Prime Minister David Cameron, to join the Vote Leave campaign.

While some might pin those troubles on cost-cutting carried out by six years of Conservative-led governments, many in Peterborough believe it's immigrants from Eastern Europe who are to blame.

Emotions are raw. "The English people who live on this street are not polite to anybody from any country. If you say, 'Hello, good morning' to them, they just go like this," says Giana Honika, a 53-year-old Lithuanian, jamming her middle finger upward in the universal gesture of insult. "Really, they do. They say, 'Go back to your country.'"

Ms. Honika, who moved to Peterborough 13 years ago and found work in a factory, now owns a café and an adjacent grocery store near the city centre, both of which offer Eastern European cuisine. She says she can understand her neighbours' anxiety over the pace of change.

"When I started this business, all these houses across the street were owned by English people. Now, all [the inhabitants] are from Bulgaria, Romania. There is just that one door over there that is still English people," she says.

John Curtice, Britain's top expert on polling and public opinion, says the split between the pro-Remain and pro-Leave camps is "between the winners and losers of globalization."

Those in the Remain camp are younger and more cosmopolitan, and often have the education and the skill sets to compete in a borderless world – people who don't need to worry about losing their jobs to someone willing to work for less. The Leave camp, meanwhile, is older, less educated and more worried by the changes they see happening in British society.

Mr. Jackson, the MP, agrees with the analysis, but puts it more simply. Peterborough, he says, "is a microcosm of the people-versus-the-establishment battle that the referendum is.

"Essentially, the people are saying, 'Look, we were never consulted about mass immigration.' "

Police on horseback escort hundreds of migrants after they crossed from Croatia into Dobova, Slovenia, on Oct. 20, 2015.

SERGEY PONOMAREV/New York Times

800,000 refugees in six tumultuous months

Judith Koller, who runs a popular wine restaurant in the town of Vogau, a short drive from Austria's newly fenced border with fellow EU member Slovenia, has always known which of her patrons voted "red" (for the Social Democratic Party) and which voted "black" (for the conservative Austrian People's Party). But those lines were erased during the 2016 presidential election campaign.

"Now, the majority voted blue," she says – meaning they supported the Freedom Party, a movement that has long been controversial in a country that counts Adolf Hitler as its most notorious son.

Ms. Koller has been voting for the Freedom Party since the days of Jorg Haider, the charismatic populist who rattled Europe as far back as 2000, when he led the Freedom Party into a short-lived coalition government with the People's Party. (Mr. Haider, who resigned as leader of the Freedom Party shortly after the formation of the coalition government, died in a 2008 car accident.) As a small-business owner, Ms. Koller says she was drawn to the Freedom Party's economic platform of lower taxes and less bureaucracy.

What convinced many of Ms. Koller's patrons to switch their vote to the Freedom Party this time was 2015's refugee crisis in Europe, which saw nearly 800,000 people – most of them Muslims from such war-torn countries as Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan – pass through Austria over just six tumultuous months last summer and fall. Thousands streamed every day through the streets of Vogau and other Styrian towns.

"People were afraid. We weren't used to this," the 53-year-old Ms. Koller recalls. "They were walking through the middle of our streets – thousands of them – and the military were making loudspeaker announcements in Arabic. It was terrifying."

A year later, the fear has scarcely subsided. Tales abound over how much financial support the refugees – who can be seen lingering in Styria's towns during breaks in their German lessons – are getting while they, in the words of Ms. Koller, "do nothing."

A series of disturbing sexual assaults involving immigrants, including that of a 10-year-old boy assaulted in a public pool and a 21-year-old student gang-raped in a Vienna park, has fed the paranoia. Parents who once let their daughters walk home from school in sparsely populated Styria now insist on picking them up in their cars.

Ms. Koller feels it necessary to clarify that she's "not a Hitler fan." She just thinks the new arrivals from the Middle East can't fit in to Austrian society.

"We just want Austria to stay Austrian," she says, a comment that draws no reaction from patrons in her packed restaurant. "We're afraid that in 50 years we'll all be forced to wear head scarves."

Even before the Freedom Party's surge, Austria's government, a coalition between the Social Democrats and the People's Party, was trying hard to appear that it was responding to such fears. A two-metre-high fence was erected in December and January along the country's border with Slovenia, which like Austria is part of both the EU and the visa-free Schengen Area.

The latter zone no longer seems to exist in practice, as every vehicle entering Austria from Slovenia is now meticulously checked.

While few refugees have made their way this far north since Balkan governments began shutting their borders earlier this year, something like a state of emergency persists in Styria, with military and police vehicles seemingly on constant patrol in towns around the Slovenian border.

"People in Vienna or Graz don't know how bad [the refugee crisis] was," says Vanja, a 35-year-old waitress in the border town of Spielfeld. "But nobody here voted for Van der Bellen. Anyone who was here doesn't want to see it happen again."

A woman passes a mural on a derelict building in Stokes Croft showing U.S. presidential hopeful Donald Trump sharing a kiss with former London mayor Boris Johnson on May 24, 2016, in Bristol, England.

Matt Cardy/Getty Images

A continent long plagued by identity politics

Few believe Europe's surge to the right will stop soon. A vote for a Brexit on Thursday would almost certainly presage the end of Mr. Cameron's premiership, likely ushering in a government headed by Conservative rebel Boris Johnson, whom many in the British press – and some cabinet colleagues – have labelled a better-educated version of Mr. Trump.

Mr. Johnson's populist instincts have been on display since he took over de facto leadership of the Vote Leave campaign. The pro-Brexiters deftly switched from arguing with the Remain side over the economic benefits and drawbacks of the EU, to hammering home a message that Britain needs to leave the 28-member bloc in order to curb immigration.

More significantly, a vote for Brexit would add resonance to Ms. Le Pen's message that France – traumatized by last year's terrorist attacks in Paris – also needs to quit the EU. (A Pew Research Center survey published earlier this month found anti-EU sentiment was even higher in France – where 61 per cent had negative views of the bloc – than in the UK, where 48 per cent were negative versus 44 per cent positive.)

A strong showing for Ms. Le Pen, who is expected to make it into a second round run-off in next year's presidential election, though no further, would in turn inspire other far-right parties around the continent.

"I do not see this as a blip. The Austrian election will probably, in a couple of decades, be seen as the election where it all started. It is very likely that, in the near future, we will have here in Europe – among [the EU's] 28 heads of state and government – at least a couple of right-wing populists," says Christoph Hofinger, director of the Institute for Social Research and Consulting, a polling firm in Vienna.

Mr. Hofinger sees similar conditions aiding the rise of the populists both in Europe and an ocean away in the United States. "There is a growing number of voters with declining economic prospects and optimism. That is the soil where populist movements may grow."

Donald Trump, of course, has become the modern face of the populist demagogue, a title he has earned with his calls for a wall along America's southern border in order to keep out Mexicans – whom he has derided as "in many cases criminals, drug dealers, rapists" – and a ban on Muslim immigration to the U.S. (as well as immigration from countries "with a proven history of terrorism against the United States").

But Ian Bremmer of the Eurasia Group, a New York-based political consultancy, says Mr. Trump's unexpected rise to become the Republican Party's presumptive presidential nominee is in some ways less worrying than what's happening in Europe.

Mr. Bremmer believes Mr. Trump's stab at the presidency will likely prove a high-water mark for his brand of politics: Mr. Trump's message appeals to older white Americans, a group that is a slowly shrinking part of the electorate; few younger Americans are receptive to Mr. Trump's ideas.

Demographics, Mr. Bremmer says, play a less obvious role in the nationalism flaring up across Europe, a continent long plagued by identity politics and quests for ethnic homogeneity.

"Anti-immigrant sentiment is not just a dog whistle [in Europe]. There's something very real there, and it's bound up in European nationalism, which has been a problem for a long time."

A mourner pays tribute to slain Labour MP Jo Cox at a vigil in Parliament square in London on June 16, 2016.

DANIEL LEAL-OLIVAS/AFP/Getty Images

'So much anger against each other'

Among the eclectic addresses that line Lincoln Road is the U.K. headquarters of Radio Star, which broadcasts Polish news and music aimed at the 550,000 Polish speakers who live in Britain.

The staff of Radio Star are an example of the EU at its best – young and multilingual, and believers in a Europe of free movement and free speech.

But the Brexit debate, and the growing possibility of a Leave-side win, have rattled Radio Star's broadcasters, who find themselves wondering if they'll soon need to be applying for work visas to stay in the U.K.

Inviting parents or friends to visit them in Peterborough would suddenly become more complicated after a Brexit, and the idea of living and working in the U.K. would be far less attractive.

Britain's debate is very much about Radio Star and its audience. But while Commonwealth citizens, including Canadians living in the U.K., can vote on Thursday, Poles and other EU citizens have no right to a ballot. They'll be watching and waiting as the country effectively votes on whether they can keep living and working as they have been.

It creates an uncomfortable feeling. "We're the subjects of the conversation without being participants in the conversation," says Gosia Prochal, a 24-year-old host at the station. The narrative that Eastern European migrants are somehow to blame for all Little England's woes clearly annoys her. "We're outsiders. People are talking about us like we're sitting here not working at all. We're a contributing part of British society, but we are voiceless."

Her boss, 34-year-old Radek Stawiarski – who also runs a recruiting agency that brings Polish workers to Peterborough – chuckles when asked what Peterborough would be like if all the immigrants from EU countries suddenly had to go home. "Everything would stop," he says.

As Ms. Prochal and Mr. Stawiarski chat about the referendum, and their concern over the anti-immigrant language used by UKIP and the Leave campaign, the conversation turns to politics in their home country. The Polish government declared in March, after bombers attacked the airport and metro system in Brussels, that it was no longer willing to accept refugees.

Mr. Stawiarski confesses he has no sympathy for the Muslims seeking asylum in Europe. "To be honest, I'm not really happy about all these Syrians," he says, sounding not unlike the Freedom Party supporters in Styria. "We have a different culture from them."

Ms. Prochal recoils slightly. "There's so much anger against each other, it's horrible," she says, speaking of both England and Poland. "People want to go backward."

Mark MacKinnon is The Globe and Mail's senior international correspondent, based in London.