It's been 30 days since protesters and police clashed on the streets of Hong Kong. Here's what you need to know about their democracy protest and what's happened over the past 30 days.

The pro-democracy protest is a month old

Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protesters have occupied downtown Hong Kong for more than a month. On Monday, protesters marked the anniversary with a moment of silence at 5:57 p.m. local time, when police shot the first of 87 tear-gas canisters in the Admiralty district on Sept. 28

Protesters are debating their next move after a vote on the movement’s direction was shelved over the weekend. Talks between the government and student leaders on Oct. 21 failed to yield an immediate solution, with the city’s No. 2 official offering to send China a report reflecting the demands of the demonstrators.

Hong Kong students leading a month of street protests for democracy are suggesting direct negotiations with senior Chinese Communist Party officials as a way to end a standoff with the local government.

The protest leaders said Tuesday that they want the Hong Kong government to convey their demands for greater democracy to Beijing. If that’s not possible, then they want to arrange a meeting with Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and other officials so they can get their views across.

When did this start?

Aug. 31:Beijing rejected demands for Hong Kongers to freely choose the city’s next leader, prompting threats from pro-democracy activists to shut down the Central financial district.

Sept. 22:Students at more than 20 universities and colleges launched a week-long boycott of classes and peaceful protests for democracy.

Sept. 26:When the student boycott ended, more protests erupted, with thousands in the streets and scores arrested by police over the weekend.

Sept. 29:Protesters defied volleys of tear gas and police baton-charges to stand firm in the centre of the global financial hub.

What do the protesters want?

Open elections: China rules Hong Kong under a “one country, two systems” formula that accords the territory limited democracy. It guarantees Hong Kong a high degree of autonomy and freedoms not enjoyed in mainland China, with universal suffrage set as an eventual goal. But Beijing’s proposed rules require that the chief executive must love China, and be nominated by a 1,200-person committee, a process critics have said gives Beijing control over who Hong Kongers can vote for. The protesters want elections with a freely chosen list of candidates.

Leung’s resignation: C.Y. Leung, Hong Kong's widely unpopular chief executive, has become a focal point of the protesters’ anger. Mr. Leung has resisted the protesters' call for him to resign.

Why the 'Umbrella Revolution'?

Parasols are fast becoming a symbol of the demonstrations after those in the Occupy Central movement bought large numbers of umbrellas to protests as makeshift shields against tear gas.

How has China responded?

Beijing has offered no compromise to Hong Kong’s crisis, with Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying bluntly saying “Hong Kong is China’s Hong Kong” on Monday.

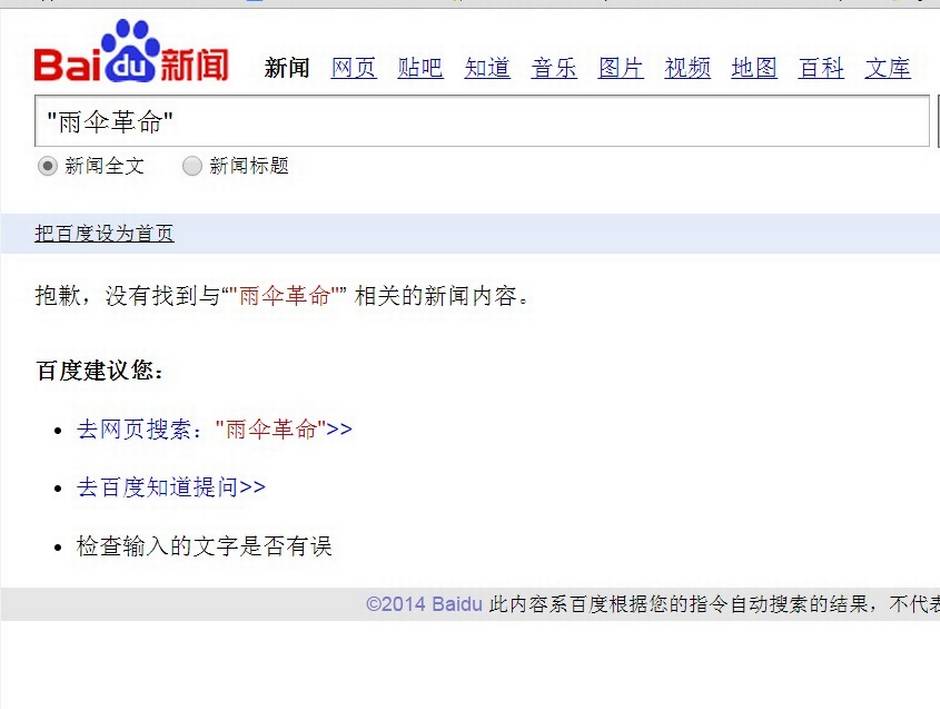

The Chinese government has heavily censored Internet discussion of what is happening in Hong Kong. Social-media sites such as Instagram, Twitter and Facebook were blocked in many parts of mainland China, and Chinese Web services like the search-engine Baidu and the microblogging site Weibo throttled what users could see about Hong Kong.

- Read more from Tu Thanh Ha on China’s Internet censorship of the Hong Kong protests.

How the world is watching

Taiwan:Televised scenes of the chaos in Hong Kong have already made a deep impression in Taiwan, which has full democracy but is considered by China as a renegade province that must one day be reunited with the Communist-run mainland. “Taiwan people are watching this closely,” Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou said in an interview with Al Jazeera.

Canada:Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird voiced Ottawa's support for the democracy protests on Twitter Sunday. On Monday, his office said Canada was"supportive of democratic development in Hong Kong."

Aspirations of people of #HongKong are clear. Canada supports continued freedom of speech and prosperity under the rule of law.

— John Baird (@HonJohnBaird) September 29, 2014The U.S. government is closely watching the Hong Kong protests and said it supports the “aspirations of the Hong Kong people,” White House spokesman Josh Earnest said on Monday. “We believe that the basic legitimacy of the chief executive in Hong Kong will be greatly enhanced if the basic law’s ultimate aim of selection of the chief executive by universal suffrage is fulfilled,” Earnest told reporters at a daily briefing.

United Kingdom:Britain’s Foreign Office said on Monday it was important for Hong Kong to maintain the right to demonstrate. “The British government is concerned about the situation in Hong Kong and is monitoring events carefully,” it said in a statement. The statement said it was Britain’s position that under the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which set out arrangements for the transfer of sovereignty over the territory, Hong Kong’s “prosperity and security” were underpinned by fundamental rights which included the right to demonstrate.

The Tiananmen factor

The Hong Kong protests are on a scale not seen in China since the 1989 protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, which ended in a violent police crackdown in which hundreds died. (An exact death toll is still not known.) The Umbrella Revolution has invited comparisons to the 1989 protests, though the scale of democratic reform being called for in Hong Kong is much smaller than at Tiananmen, where protesters sought full nationwide multiparty democracy in China.

- Read Doug Saunders’s take on the key differences and similarities between Hong Kong in 2014 and Tiananmen in 1989.

The Tiananmen comparisons are especially important for China’s current President, Xi Jinping. His father, Xi Zhongxun, is rumoured to be one of the few senior Communist Party officials to have spoken out in 1989 against the use of force on the Tiananmen protesters. Chinese liberals have held out hope that the younger Mr. Xi would share his father’s attitudes, a view challenged by Mr. Xi’s recent hardline approach to Uyghur separatists in Xinjiang.

- Read more from Nathan Vanderklippe on what the legacy of Tiananmen means for Xi Jinping.

With reports from Reuters, Nathan Vanderklippe and Mark MacKinnon