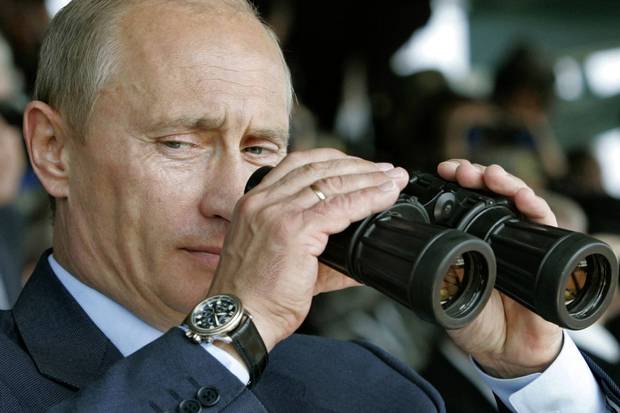

KIRILL KUDRYAVTSEV/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, whose national leaders are meeting in Warsaw Friday and Saturday, is facing its most serious challenge since the Cold War when the United States and Soviet Union actively confronted each other around the globe.

The alliance appears set to deploy four well-armed military battalions – one led by Canada – to the Baltics. They are being dispatched at the request of NATO members Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland, with the express purpose of deterring what is perceived as Russian aggression.

For its part, Russia says it is only reacting to what it perceives as Western aggression – the continental spread of alliances such as NATO and the European Union that has come to threaten core Russian interests.

"While Westerners may believe that NATO's eastward expansion has been peaceful and voluntary," says Dimitri Simes, president of the Center for the National Interest in Washington, "Russians see it as inseparable from NATO's European and global military exploits."

NATO and Russia, he says, are "on a collision course."

Leaders and ministers of NATO member states pose for a group photo at the PGE National Stadium in Warsaw on July 8, 2016.

ALIK KEPLICZ/ASSOCIATED PRESS

WHAT TRIGGERED THE CRISIS?

To NATO, the crisis started with Russia's March, 2014, seizure of the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine and the subsequent Russian support for separatists in Ukraine's eastern provinces. NATO said it would stand by Ukraine, which had become a partner of the Alliance, although not a member, and has given it financial and military assistance.

A Russian Army officer helps an armored personnel carrier drive on a street in Sevastopol, Ukraine’s Black Sea port, on Feb. 25, 2014.

ANDREW LUBIMOV/ASSOCIATED PRESS

To Russia, however, the trouble began before that, with NATO and the European Union encouraging newly independent Ukraine to abandon its non-aligned status, to break many of its historic ties to Russia, and to become a more European partner.

For Russia, which maintains an important naval base in the Crimean port of Sevastopol, home to Russia's Black Sea Fleet, such a shift posed a strategic threat.

A Russian warship is seen in Sevastopol, Crimea, on Feb. 23, 2016.

PAVEL REBROV/REUTERS

"Russia's elite and much of its public believes that Russia can never be secure if Ukraine becomes a hostile nation and particularly if it joins a hostile alliance," notes the Moscow-born Mr. Simes, a noted Kremlinologist during the waning years of the Soviet Union. "A NATO influenced by not only Poland and the Baltic states, but also Ukraine, may form an existential threat for Moscow," he says.

The European Union responded to Moscow's actions in Ukraine by imposing economic sanctions on Russia. They have had little effect.

Since then, the two sides have engaged in tit-for-tat measures of intimidation. NATO has deployed weapons – including ballistic missile defence systems – to forward positions on the Russian front, and Russia has moved thousands of troops into the theatre; both sides have issued bellicose statements and each has carried out an extensive array of muscle-flexing military exercises in the area. Tensions have been ratcheted higher and higher.

"NATO is strengthening its aggressive rhetoric and its aggressive actions near our borders," said Russian President Vladimir Putin last month. "In these conditions, we are duty bound to pay special attention to solving the task of strengthening the combat readiness of our country."

TIMELINE: EUROPE AND RUSSIA'S PATRIOT GAMES

TRISH McALASTER/THE GLOBE AND MAIL (SOURCE: INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF WAR, WASHINGTON)

THE REGIONS AT THE FRONT

The Baltic states

In the late 1990s, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were among the first of the newly independent former Soviet states to seek membership in NATO. It seemed a no-brainer to welcome them to the club.

But these small isolated countries, bordered mostly by Russia, are almost impossible to defend. This was a point driven home by a Rand Corporation report early this year.

"As currently postured, NATO cannot successfully defend the territory of its most exposed members," the authors said, noting that it would take less than 60 hours for Russian forces to overrun two of the three countries.

Alarmed by the increase in Russian manoeuvres off their shores and a steady increase in overflights by military aircraft and drones, the Baltic States called for the alliance to step up. The result is likely to be the deployment of four NATO battalions, including one to neighbouring Poland.

However, some question whether this threat is real.

"What would Russia gain from attacking the Baltics?" asks Doug Bandow, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute. "A possible temporary nationalist surge at home? A likely short-lived victory over the West?"

"The costs would be far greater," he argues. More likely, there would be a population exodus, economic collapse, resentment at home for launching a war without pretext and a slammed door on any economic relationship with the West.

By all means NATO should act to reduce even minimal chances of war, Mr. Bandow agrees, "but everything about Putin's presidency so far argues against reckless war for no rational purpose against the Baltics."

A multibillion-dollar NATO buildup certainly is not called for, he argues, and it would only "create a perceived threat to Russia where none currently exists."

Canada sending 450 troops to Latvia as part of NATO force

1:28

The Balkans

There already is considerable division in this predominantly Slavic region over what kind of future people really want. For the past several years most have sought a European identity with membership in the European Union and NATO. The economic benefits have been attractive.

Now, many are having second thoughts. The apparent rise of xenophobia brought out by the migrant crisis in Western Europe, has made people worry about how they would fare in the EU.

Moscow has been actively wooing people in many of these countries, notes Denisa Kostovicova, a Balkans specialist at the London School of Economics. Mr. Putin's United Russia Party recently signed a joint declaration with a number of political parties across the Balkans affirming popular desire to remain "neutral sovereign states" and not members of NATO.

"This could become a strategic document," Ms. Kostovicova said, and "a snub to any ideas that politicians in the Balkans may entertain about the expansion of NATO."

Already, Slovenia, Albania and Croatia are full NATO members, and Montenegro, the latest NATO aspirant, only awaits ratification by NATO members.

People wonder now if such ratification will be forthcoming and whether NATO's open-door policy will close once Montenegro is admitted.

WHY RUSSIA REACTED SO VEHEMENTLY TO NATO'S EXPANSION

NATO's open-door policy to the countries of Eastern Europe was born in the euphoria of the post-Cold War 1990s and was enthusiastically promoted by the Bill Clinton presidency in the United States (1993-2001).

Whereas the George H.W. Bush administration (1989-93) had viewed the new Russia as a friendly power and had no plans to expand NATO, Mr. Clinton had other ideas and sought to sign up as many new members as possible.

"The Clinton administration had every legal right to proceed with NATO expansion," acknowledged Mr. Simes. "What U.S. officials had no right to do," he said "was to think that they could move NATO's borders further and further east without changing Russia's perception of the West from friend to adversary."

Clinton-era NATO interventions in Bosnia and Serbia, as well as the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the 2011 action in Libya cemented Russia's perception of NATO as a threat, he said.

"Remarkably," Mr. Simes wrote in an essay this month in The National Interest journal, "NATO failed to consider how its dramatically different conduct would affect relations with Russia."

On June 30, in a speech before Russia's senior diplomats, Mr. Putin said that NATO's military buildup near Russia's borders "is aimed at undermining a military parity that has formed over decades."

However, he added, "we aren't going to succumb to militarist frenzy."

Rather, he said, Russia remains committed to developing a common economic space with Europe "from the Atlantic to the Pacific," and called on NATO to join Russia in fighting their common enemy, international terrorism.

There may yet be an opportunity in there for a new beginning.

DMITRY ASTAKHOV/ASSOCIATED PRESS

WHAT RUSSIA IS WATCHING FOR

- Whether NATO will deploy four battalions to the Baltic states and Poland

- Whether it will continue NATO’s open-door policy

- Whether it will increase military support for Ukraine

- Whether it will establish a Black Sea fleet

Follow Patrick Martin on Twitter: @globepmartin