As he was climbing the ranks of the world’s richest people a few years ago, the Brazilian entrepreneur Eike Batista vowed to bring a long-lost pride back to Rio de Janeiro, his adopted hometown – saying it would once more be the “city of the sun,” a new world hub.

Today the sun still shines in Rio, but Mr. Batista holds the grim distinction of being the planet’s most indebted person, out 99 per cent of a $34.5-billion (U.S.) fortune, and the city he pledged to remake is littered with the debris of his shattered ambitions.

The once-iconic Hotel Gloria, which he bought and pledged to restore to grandeur for the 2016 Olympics, is shuttered and decaying. The polluted lake in the heart of the city that he promised to rehabilitate lies rank and fetid in the summer heat. Dozens of police cars he bought for a project to bring security to favelas sit idle, with no one to buy gas or maintain them. At his former corporate headquarters, front windows are splintered and no one has bothered to fix the glass.

Mr. Batista’s epic rise in recent years paralleled that of his country, the hottest emerging market. Now Brazilians are hoping that their nation, tipping into recession and beset by inflation, will not similarly parallel his fall.

“Two years ago Eike was Mr. Brazil – well, Mr. Brazil is a fraud, so what does Brazil have to offer now?” said a former director of his companies who worked closely with Mr. Batista for 14 years, and quit as the bankruptcies mounted. Because the case is before the court, and he faces scrutiny, he was not willing to be speak on the record.

Brazilians are watching in grim fascination as Mr. Batista’s life falls apart. Last week, police repossessed the white Lamborghini he kept in his living room, along with watches and a piano from the palatial home where he now lives a reclusive life. This week they seized his yacht, while his ex-wife had a screaming fit outside the walls of his mansion, saying she was moving back in since police were taking away her assets, too.

Mr. Batista, 58, is not just spectacularly broke: he is on trial for collusion, insider training, money-laundering and “crimes against the financial market,” and legal experts say he stands a good chance of being the first person ever to go to jail for financial crimes in Brazil.

Mr. Batista has denied any wrongdoing. His lawyer, Sergio Bermudes, declined repeated requests for an interview. The case is expected to go on for years, in Brazil’s infamously slow legal system.

Mr. Batista’s father, a Brazilian businessman, married a German woman while studying in Hamburg. A widely respected figure in Brazil’s industrial development, he went on to become president of the mining giant Vale and served as Minister of Mines and Energy. Mr. Batista was born and spent his early years in central Brazil but moved to Germany when he was 12, and studied metallurgical engineering there, although he did not complete college.

At 22 he returned to Brazil and, as he has told the story, borrowed $500,000 from contacts to go to the Amazon where he bought gold from artisanal miners who panned it in the river beds and abandoned mines, and then sold the gold back in the city for vastly higher prices. He made millions fast, and used it to start buying mines of his own, in partnerships with connections of his father’s, he has said.

In 1983, Mr. Batista and backers took over a small Canadian mining company called Treasure Valley, listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange. They renamed it TVX: Mr. Batista’s firms always had an X in the name, to signify the multiplication of wealth. He presided over international expansion as CEO, but poor management and a sharp drop in the price of gold wiped out 96 per cent of the company’s value and it was eventually sold off.

Mr. Batista, however, showed a remarkable ability to persuade investors – both private and institutional – to sign on to his schemes. He set out to chart a new course at a pivotal moment for Brazil, with a commodities boom and market liberalization pushing a huge economic expansion.

In 2001 he built a thermal power plant in northern Brazil, the first project of an energy company called MPX. In 2005, he founded MMX, his mining firm, feeding the Chinese appetite for iron ore, and held a public offering a year later. In 2007 he launched the petroleum firm OGX, with backing from the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, and took it public the next year. He started companies to provide logistics and services to his extractive businesses, and invested nearly $2-billion to build a giant port complex that was to be the centrepiece of a redevelopment of Rio.

“This was something new in Brazil – all of these IPOs,” said the former director of Mr. Batista’s holding company. Brazil’s stock exchange is relatively tiny, with the same number of companies as that of Mongolia.

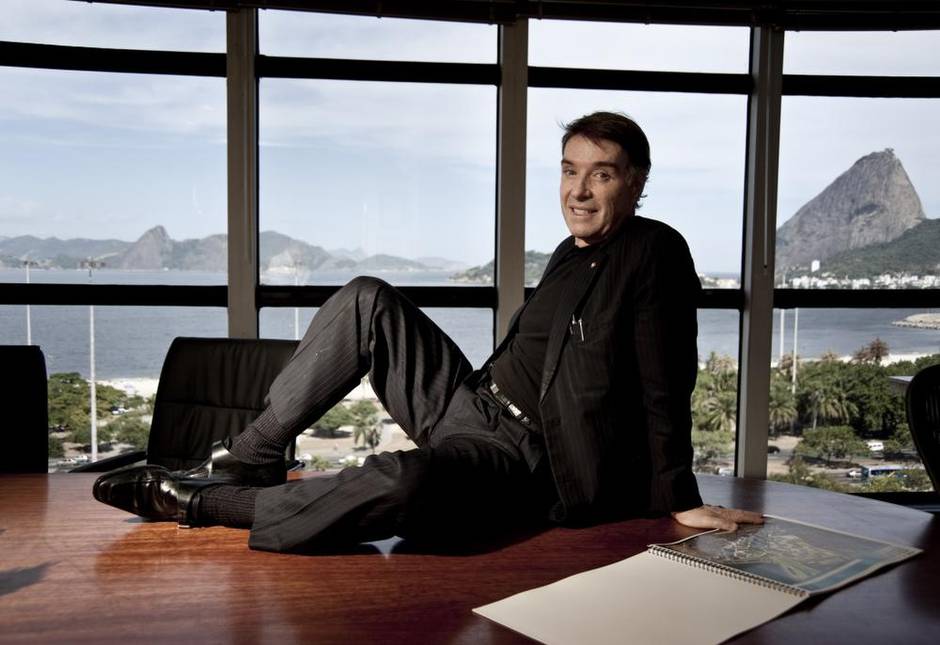

All along the way Mr. Batista boasted of his close ties to government – and was photographed with the president and governors and celebrities – and lived large, cutting an ostentatious figure of swashbuckling wealth. He anchored an enormous yacht in the Rio harbour and won a number of international titles racing speed boats from his collection. By 2012 he was the seventh wealthiest person in the world, according to the Forbes list, and talked confidently of when he would be Number One. He showered his largesse on the city, funding a children’s hospital and sponsoring sports and cultural events.

Except, says the former executive in the holding company EBX, it wasn’t actually his money: The donations were made in the name of OGX and other companies. “He didn’t do anything with his own money: He spent other people’s,” he said.

The story of Mr. Batista’s unravelling, in essence, is this: He bet big on the “pre-salt” oil fields 200 kilometres off the coast of Rio and more than two kilometres under the sea, raising more than $3-billion from the sale of shares in OGX. But when Mr. Batista began to drill, he didn’t find oil, not on the scale he needed.

Yet he allegedly kept this information to himself, and instead said independent surveyors had asserted that his fields had 10.8 billion barrels of reserves. And the value of his companies rose and rose – until in 2012 OGX’s financial statements made clear that vast sums were being spent on drilling, and very little was coming out of the ground. The share price tanked, and he defaulted on loans.

“His projects made sense at the time – big oil, and then the big port to move it, and the logistics companies,” said Sergio Leo, author of a book on Mr. Batista, The Rise and fall of the Empire of X. “But each company was linked to the success of the other. And the moment OGX failed it went down like a house of cards.”

Soon the X companies were being broken up, sold or ordered into bankruptcy protection. The Ontario teachers fund got out before the carnage, but many minority shareholders were hit hard. “There are lots of arguments he can present to show it was good faith, when he was encouraging people to invest, but it will be difficult to believe because at the same moment he was selling his own shares,” said Mr. Leo. “He knew the company was in bad condition and the fields were not the size publicized, so he knew he would have a big hit in profits. But at the same time he was on Twitter telling people to invest, while he was selling his own shares.”

The former EBX director echoed this assertion, saying he “knows for a fact” that Mr. Batista knew more than a year before it was made public that the oil fields were far less valuable than estimated.

Brazil’s weak financial regulators did not help. “If our regulators were faster probably they could have stopped him before he did so much damage,” said Mr. Leo.

It would be highly unusual for someone with Mr. Batista’s level of privilege to go to jail, and the asset seizures are also unusual for a case involving someone of his social status. Police have so far frozen $1-billion in assets. Last week’s raid on Mr. Batista’s Rio home were covered live on television.

Marcio Lobo, a lawyer who says he lost $25,000 in the bankruptcy of OGX, is representing 60 other minority shareholders in a class action suit against Mr. Batista. New people join the suit every day, he said. “For the first time people are starting to believe in our justice. Before people said he was too rich and too powerful to get our money back. Now they saw police go to his house.”

But some Brazilians have limited sympathy for those who lost money on Batista ventures. “Any Brazilian investor who knew Eike knew he had a screw loose, that he was a lunatic with projects on a crazy scale,” said Ancelmo Gois, the eminence grise of Brazilian columnists who covered the Batista empire closely for years. “Nearly all the victims signed on to play the game with him. They knew what he was.There are no innocents here. There was a carnaval around Eike – champagne and sports cars. It was an orgy, and everyone knew why they were there.”

And Mr. Gois mourns his loss. Brazilian business culture is fatally timid, and chronically dependent on the state, he said, and anyone who succeeds squirrels away profits in their mattress. Mr. Batista, with his breathtaking risks and his flashy success, was different. “I’m not defending him, but his downfall is a huge loss for the city.”

Mr. Batista himself has largely gone to ground. Neighbours in his leafy hilltop neighbourhood say that while he once came and went in a cavalcade of vehicles several times a day, he now leaves in a car with a single body guard, only once or twice a week. “Before this all happened, people would come visit all the time. Businessmen, the governor, the mayor,” said one household employee in the complex, who would not give his name. “Now, after the scandals, no one comes any more.”

Mr. Batista also no longer presides over the dining room of Mr. Lam, an upscale restaurant said to be the favourite of all his acquisitions, where he used to spontaneously pick up the tab for everyone in the room. “He’s working,” said the former EBX director, saying Mr. Batista spends his days trying to hustle up new projects – with partners from Asia, he tells his former employees. “That’s all. He doesn’t have any friends or family.”

In fact Mr. Batista has two sons, Thor and Olin, with his ex-wife Luma de Oliveira, a former Carnaval Queen and Playboy playmate. The sons, 22 and 18, are known for their sports car collections, flying the family jets to DJ parties, and bragging of never having read a book. Their relationship with their father, say former associates of Mr. Batista, is poor. He has a toddler son with a Rio lawyer who now runs a website to sell used designer clothes.

“The truth is I don’t have anything personal against him, I know he’s a father, he has three sons. I’m also a father, I also have sons,” said Mr. Lobo, about the raids. “Having the police come to your home and take your car, take your phone – it’s terrible. But he should have thought of that sooner. He had the opportunity to make things right.”

Mr. Leo, the biographer, said that one cannot compare Mr. Batista’s situation with Brazil’s. “Eike’s situation is irreversible; he will never go back to the good old times,” he said. “Brazil is facing the consequences of bad choices in the past, but it has natural and human resources that will allow us to think about a comeback.”