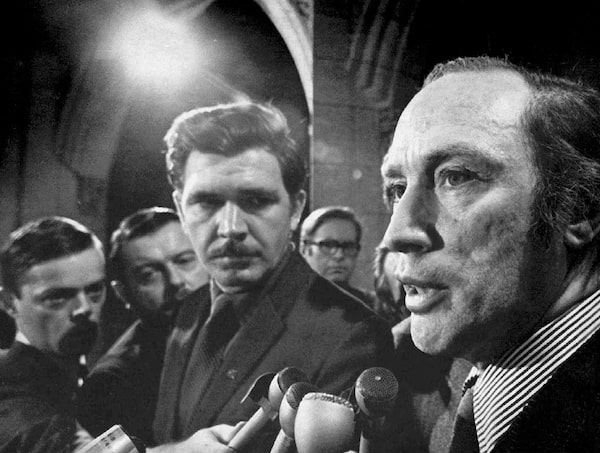

Pierre Trudeau updates reporters in Ottawa on the status of kidnapped British diplomat James Cross on Dec. 3, 1970.The Canadian Press

Robert Bothwell is the May Gluskin Chair in Canadian history at the University of Toronto. John English is professor emeritus at the University of Waterloo. Paul Marsden is a former NATO archivist. Timothy Sayle is director of the Canada Declassified repository at the University of Toronto.

For the Bloc Québécois in Parliament, the 50th anniversary of the 1970 October Crisis was an irresistible quarry, symbolizing Ottawa’s ruthless repression of Quebec nationalism through the deployment of troops, the use of the War Measures Act, and the arrest of some hundreds of people in response to the terrorist kidnapping of a British diplomat and a Quebec cabinet minister. The Bloc’s arguments failed to convince the House of Commons and the resolution demanding an apology was soundly defeated. Nothing new about that.

And nothing new, either, about the narratives and analyses and letters to the editor that appeared, pro and con, in media outlets recently. The history of the October Crisis is frozen in time. The critics of 2020 repeated, probably unconsciously, the arguments of the 1970s. To be fair to these critics, they had little more to go on than the journalists, historians and filmmakers of the 1970s. A recent book on the psychology of the U.S. President had the wonderful title, Too Much and Never Enough, and that can be applied to the October Crisis: too much heat, not enough light.

Regrettably, even nuanced analysts who claimed to present the “true story” could not. History requires evidence, but most federal government documents on the October Crisis remain locked up in closed and scattered archives. Ironically, scholars seeking Canadian historical documents in 1970 were far better served in researching events 50 or even 30 years earlier than they are today.

We do have many participant memoirs and hundreds of articles in both official languages, but there is a paucity of primary sources against which these accounts can be verified. There are some. The cabinet minutes became available 20 years ago but many parts are blacked out in accordance with the Access to Information Act. Canada Declassified, a Canadian effort to replicate the invaluable National Security Archive in Washington, has recently put online declassified documents related to the federal government’s Task Force on Kidnapping. Using the Access to Information Act, others have pried free a few nuggets. These represent, however, only surface mining of the data mountain.

The key decision-making body during the crisis was the cabinet committee on security and intelligence, which received all the briefings from the RCMP, the Canadian Forces, and the solicitor-general as well as the written briefs and formal cabinet memoranda provided to the key ministers. A few documents from the committee were made public but, to our knowledge, none of the other documents. In the case of the RCMP records, which were transferred to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) in 1984, more documents have been released than by any other government institution. Alas, a disproportionate number of pages are blanked out, legitimately if they reveal the names of informants or agents. Yet, the high proportion of blanked pages suggests that every FLQ cell was riddled with spies, which existing evidence suggests is untrue.

The creation of CSIS followed the McDonald Commission, which reported in 1981 on the activities of the RCMP Security Service. During its work, the commission hoovered up hundreds of files from the RCMP Security Service, the solicitor-general and other relevant institutions. The location of these files is unknown, leaving a gaping hole. Without the records of the solicitor-general and their direction of the RCMP Security Service, how does one judge the gravity of the threat and the proportionality of the response? Nor have the Canadian Forces opened documents on their deep involvement in the crisis. Where is the “Lessons Learned” report that surely was made in the aftermath of the Forces’ deepest engagement in a domestic crisis?

There is a way forward. In 1979, Craig Brown, the president of the Canadian Historical Association, warned that the creation of the Access to Information Act meant the end of automatic declassification of all government records, subject to national security and privacy concerns, after 30 years. While journalists and scholars welcomed the right to access more recent documents, it came at a high price, financially and historically, because each document had to be scrutinized by what became a growing army of assessors. Astonishingly, more records were disclosed between 1967 and 1983, when the Act took effect, than in the 37 years following.

Canada is now the only North Atlantic Treaty Organization country without a declassification policy, something recommended by NATO itself. Fortunately, Information Commissioner Caroline Maynard, who is currently dealing with more than 500 complaints relating to non-disclosure of historical records, understands this situation. Moreover, recent press reports indicate the government is considering the creation of a national declassification centre. We believe such a centre is imperative if Canadians are to have the documents their government created that explain the good and bad in our past. What Mr. Brown feared, “a perpetual exemption from access,” has become true as Canada has failed to carry out any systematic declassification for more than 37 years. It’s time to lift the curtains and finally see the players and the plays on the full stage.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.