Karl Lehmann and August Plaszek were German prisoners of war killed at a camp in Medicine Hat, Alta., in the 1940s.Handouts

Nathan M. Greenfield is a military historian in Ottawa who has written four books on prisoners of war in both World Wars. He is also the North American correspondent for the London-based University World News.

In November, 1941, more than two years into the Second World War, Afrika Korps private August Plaszek was captured near Tobruk, on the coast of Libya. The balding and diminutive man, who was among 275,000 German and Italian soldiers under the command of general Erwin Rommel, was described on his prisoner-of-war form as having a fair complexion, slightly baggy eyes and an overall “farmer appearance.”

In May, 1943, Sergeant Karl Lehmann – a translator for the Luftwaffe, the German air force – was captured near Tunis. A balding and overweight former university professor, he spoke several languages in addition to German, and he had a reputation as a libertine.

Plaszek and Lehmann became two of the nearly half-a-million PoWs captured by the Western powers, and by Germany and Italy, to be protected by the 1929 Geneva Convention. (Because Russia did not sign the convention, Germany did not provide protections to Russian PoWs, and vice versa; Japan infamously did not sign the treaty, either.)

The convention set out in detail how PoWs were to be treated and housed by their “detaining power,” or the country that captured them.

A perhaps lesser-known aspect about Canada’s war contribution is that our efforts included accepting about 35,000 German PoWs on behalf of Britain and placing them in camps dotted across the country.

The two largest, holding roughly 12,000 men each, were in Alberta: Camp No. 132, in Medicine Hat, and Camp No. 133, in Lethbridge.

The camps developed Nazified leadership and their own violent “Gestapo,” right here on Canadian soil.

It was in Camp 132, on the same site where the Medicine Hat Stampede fairgrounds sit today, that Plaszek and Lehmann were destined to die at the hands of their own countrymen. That, on its own, is a remarkable story.

But what came next – the investigations of their murders by the RCMP and then by military police, followed by trials of the three men charged with killing Plaszek and the four charged with killing Lehmann, whose hangings would comprise the last mass execution in Canadian history – is remarkable, too, because it was a miscarriage of justice.

Diagrams of the crime scene show the corner where Lehmann's body was found in September, 1944, and its location in a lecture room in building DZ. Plaszek was killed more than a year earlier.Courtesy of Galt Museum & Archives

Over the course of the war, Camp 132′s prisoners of war and Medicine Hat’s residents – of whom there were only about 13,500 at the time, not many more than the number of PoWs in the camp – actually co-existed peacefully. Prisoners worked on local farms for full wages; as a special privilege, certain senior non-commissioned officers were allowed to walk the city’s streets in German uniforms. The girls’ high-school glee club even gave a Christmas concert in the camp in 1943.

But in late July that year, rumours began circulating in town that a PoW had been murdered. On July 23, a guard in a watchtower had seen Plaszek being dragged by his heels in the direction of a recreation hall. He was later found bloody, beaten and lifeless, hanging from a rafter. The town coroner and undertaker, who handled the body, were likely the only civilians who knew that the man had also received a heavy blow to the head.

Fourteen months later, on Sept. 10, 1944, Lehmann was called from his barrack to a classroom hut. There, he was supposed to sign language-proficiency certificates for a number of men who were among the thousands being moved to the PoW camp in Neys, Ont., to make room for Germans captured in Normandy. The next morning, his lifeless body – his face battered to a pulp and with a rope, tied to a gas pipe, wound around his neck – was found in a corner of the classroom.

His comrades had determined Lehmann was “the head” of a communist group seeking to overthrow camp leadership. (The PoWs were wrong, but Lehmann was a traitor who fed information to Canadian authorities.)

The RCMP and military police investigated each killing, but none of the PoWs would name names. After Plaszek’s death, a German-speaking Mountie disguised as a maintenance worker was inserted into the camp, but that effort also failed to garner names. But he did confirm that a hardcore group of Nazis controlled the PoWs’ lives with the help of a Gestapo-like group of thugs who beat up or tortured anyone suspected of disloyalty to Germany.

The RCMP had their suspicions about which PoWs were involved in the killings. But it wasn’t until the war had ended that the RCMP broke the case and arrested seven men, thanks to an anonymous letter from an inmate left on a typewriter in the camp in Neys.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/RCMGD5UD6VFDDCF55PVOC5I5ZM.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/32ROLEJDONGMZGEVDKOCFWGWWQ.jpg)

Werner Schwalb was a baker before the war, and became a gunner in a Panzer tank during the Blitz through France in 1940 – earning an Iron Cross First Class before being captured in Egypt. Witnesses reported seeing him “with blood on his hands” in the hall where Plaszek was found dead.

It took only 37 minutes for the jury in Schwalb’s case to find him guilty of murder. William Robinson Howson, the chief justice of the Alberta Supreme Court Trial Division, sentenced him to be “hanged by the neck until you are dead.” (The second German accused, who was viewed as young and impressionable by the jury, was found guilty but had his death sentence commuted; the third was acquitted.)

Schwalb’s lawyer appealed, arguing that under the Geneva Convention, German PoWs were still subject to German military law, and that their dealing with traitors in their midst could reasonably be understood to be the carrying-out of military orders.

“If a Canadian in a German prison camp had an honest belief that one of their group was a traitor and, in a melee, this Canadian was killed, surely the government of Canada would not execute Canadian soldiers who had taken part in the melee,” the defence argued.

The appeal was unsuccessful. On June 27, 1946, Werner Schwalb was walked to the gallows and positioned over the steel trapdoor. Before it opened, he called out in English: “My Fuhrer, I follow thee.”

The four PoWs charged with killing Lehmann each had an impressive service record. Flight sergeant Willi Mueller logged 86 flights, and earned an Iron Cross First Class and an Iron Cross Second Class. Flight sergeant Bruno Perzenowski was a policeman before joining Germany’s war effort, and wore an Iron Cross First Class. Sergeant-major Heinrich Busch clerked in a clothing store before the war and flew 26 missions for the Luftwaffe, receiving an Iron Cross First Class and an Iron Cross Second Class before crashing over England. And Walter Wolf, a prewar town financial inspector, had fought in France and earned an Iron Cross Second Class before being captured at the Halfaya Pass.

The question the defence would ask again and again in the trials of the four PoWs was whether they were within their rights – as German soldiers following orders – to kill a man in their midst they considered a traitor. It was a killing, to be sure. But was it unlawful – especially since, after a small group of German military leaders failed to assassinate Adolf Hitler with a briefcase bomb in July, 1944, they heard an order to liquidate traitors on a short-wave radio that had been secreted in a model of a ship?

And under whose law should that question be answered? Witnesses told the court that PoWs in Camp 132 exercised a certain “sovereignty” over life in PoW camps. The prisoners elected their own leadership, maintained their command structures and upheld order to their own standards. In fact, just as the Americans did, Canadian authorities relied upon PoW leadership to keep discipline in the camp and to punish their own for transgressions according to German military law.

An extreme example of this was the “degradation ceremony,” during which PoWs who transgressed the German Military Code’s prohibition on homosexual acts were stripped of their rank and decorations. Often, after such ceremonies, these PoWs were savagely beaten while both the German camp leadership and Canadian authorities turned a blind eye.

So the accused could not be guilty of murder, argued the defence, because they owed fealty to the Reich. The killings of Plaszek and Lehmann, lawyers said, were more analogous to executions carried out by military tribunals, or the shooting of deserters on the battlefield.

The accused had “patriotic” motives, lawyers claimed, and the killings should be “regarded as political” rather than personal acts. What’s more, had the defendants not complied with orders to eliminate traitors, the suspicion of traitorous intent would fall upon the defendants, and their lives would have been endangered under German law. They also feared that, were they to be returned to a Germany still run by the Nazis, they would be shot. And so whole sections of the Wehrmacht’s military disciplinary manual demanding the death penalty for treason and for attempts to “undermine discipline” in the army were read into evidence.

The defence further argued that Howson’s civilian court did not have jurisdiction to try the PoWs. In this, the defence cited the Geneva Convention – which stated that PoWs were subject to the military law of the detaining powers – as well as Canada’s War Measures Act, which held that if a district military officer was unable to administer a summary sentence or otherwise dispose of a case, “he shall take steps to bring the accused to trial before a military court.”

In response, prosecutors were quick to note that the convention also said that PoWs were subject to the general laws of the detaining powers, which was true. But other jurisdictions, including the United States, read the document as requiring military justice, rather than civilian justice, for PoWs.

This distinction was key, because of the significant differences between military trials and civilian justice. Were a Canadian commanding officer to have shot a battlefield deserter, Canada would not ship him home to stand trial in a criminal court; the killing would be handled within the military justice system and, likely, would have been understood as an act of war, not a murder.

Also, according to British military law – under which Canadians served – death sentences could only be passed “by the concurrence of all members” of a five-member panel or jury made up of serving military officers, not civilians. It was assumed that military officers recognized that different principles apply to serving soldiers than to civilians.

The wording of the War Measures Act allowed the prosecution to argue that military officers had the scope to communicate with civil powers “in order that the accused may be dealt with by a civil court or criminal jurisdiction.”

The defence countered that “there is no evidence before you that the district officer commanding this district requested this court to deal with the charge against the accused.”

After the federal justice minister agreed that the RCMP would lead the investigations, it appears that the civil authorities simply assumed jurisdiction for the trials because of bureaucratic inertia.

Guard towers at Camp 132, circa 1948. Guard towers at Camp 132, circa 1948. Prisoners here would elect their own leaders and mete out a form of justice based on German military law.Courtesy of Esplanade Archives

For Howson’s part, the notion that he had no jurisdiction over the killing of Lehmann on Albertan soil was plainly annoying. In an exchange with defence counsel with the jury out of the courtroom, he asked, “What you are saying is this: that the internment camp out here is, in essence, a part of Germany? … And the law of Canada does not apply, that is what you are saying?”

When the defence answered affirmatively, the judge countered that “the land comprised in the Prisoner of War Camp, No. 132, at Medicine Hat, is part of the Dominion of Canada … merely an area of land fenced in for the safe-keeping of German prisoners of war.” It followed that the “law of Canada relating to criminal offences within that area is the same as applies to all other parts of Canada.”

Further, Howson said this “court has jurisdiction to try criminal offences committed in Alberta by those persons residing within that enclosure in the same manner as by those persons residing outside of its boundaries.”

Howson was equally emphatic in his charge to the jury: It was “a matter of law – and you must accept your law from me – that there was no law in force in that camp which authorized any one to give an order, or any other authority to kill Lehmann. There was no court, or other tribunal, or committee of any kind whatsoever in that camp that had the power to sentence Lehmann to death.

“If, as a fact, there ever were such an order in existence, no matter from how high up it came, it was an unlawful order, and was an unlawful act, and those who carried out that unlawful act were themselves guilty of an unlawful act.”

And so, in their separate trials, Lehmann’s four attackers each left Howson’s court with the same dreaded words from the bench ringing in their ears: “I sentence you to hang from the neck until dead. May God have mercy on your soul.”

Again, there were appeals. The defence, among other arguments, claimed that Howson did not have jurisdiction to try the men because there was no evidence that the military authorities had waived jurisdiction and asked the criminal court to handle the case. But again, the appeals were unsuccessful.

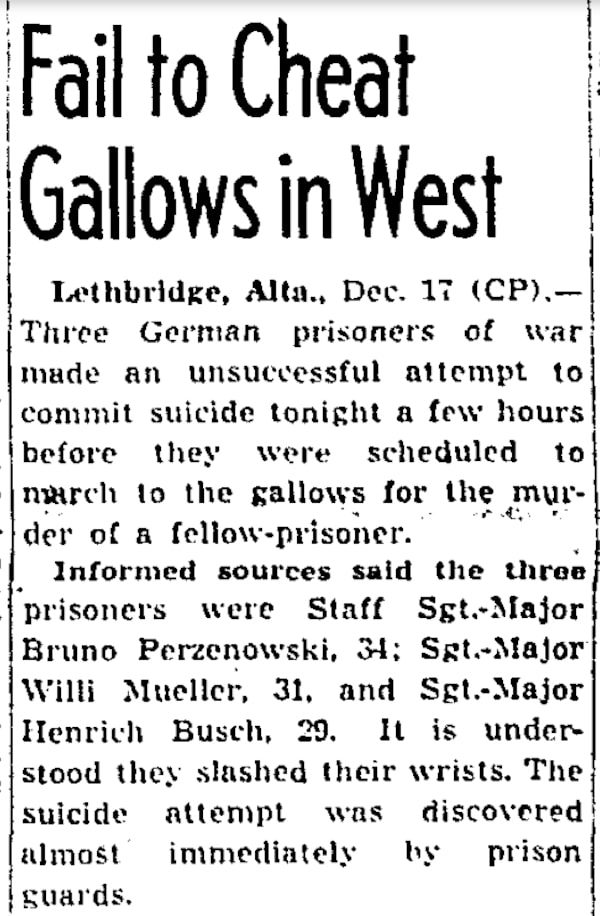

On Dec. 16, 1946, the four German PoWs were told that all legal avenues had been exhausted and that they were going to hang early on Dec. 18 – alongside Donald Sherman Staley, a Canadian army veteran who had confessed to murdering and sexually assaulting children.

Three of the PoWs – proud members of what had been the Luftwaffe and the Afrika Korps – were disgusted to learn that they would not be shot as soldiers, but would instead hang with a killer of children, and they tried to commit suicide, slashing their arms and wrists with razor blades. But a guard spotted the blood, and they were rushed to the hospital, where their wounds were dressed. The condemned men were then transported back to the Lethbridge jail to await their fate.

Shortly before midnight on Dec. 17, Bruno Perzenowski and Heinrich Busch climbed the 13 steps of the gallows to stand over the two steel trapdoors. At 12:10 a.m. on Dec. 18, the hangman pulled the lever; 20 minutes later, the two were cut down, pronounced dead by the coroner, and carried to the common grave the convicts had been forced to dig the previous day. At 12:45 a.m., Walter Wolf and Willi Mueller were executed and brought to the common grave. Finally, Staley was hanged – bringing an end to what would be the last mass hanging in Canadian history.

An article in The Globe and Mail on Dec. 18, 1946, notes the German POWs' efforts to kill themselves before a death sentence could be carried out.The Globe and Mail

By today’s standards, 76 years later, was justice done?

Almost certainly not.

A plain reading of the Geneva Convention argues that the trials should have occurred in military courts. Canada was a signatory to the convention and was generally punctilious in following it, if only in hopes that Germany and Italy would follow the same provisions in the treatment of Canadian PoWs held in those countries. The War Measures Act, too, called for a military court; it allowed for exceptions in certain circumstances, but they were not met in these cases.

By trying the PoWs in civilian court, Canadian authorities deprived them of something vitally important: jurors of their peers – that is, jurors who understood military ethos. There may have been veterans scattered through the juries, but no juror was a serving military officer, and no jury had a majority of veterans.

Accordingly, the men who judged the evidence and rendered the verdicts sending these PoWs to their deaths had (at best) an incomplete or outdated understanding of military culture, and likely a different appreciation of the requirement to follow orders. The defendants would have had a much better shot at leniency in a military court.

Howson’s opinion – that Camp 132 was part of the Dominion of Canada – ignored the fact that the world within the wire was more contested. Geneva recognized that PoWs remained subject to their army’s laws, even while being subject to those of the country in which they were prisoners.

Thus, for example, Canadians could punish attempts to escape, but had to recognize that such attempts were legal in German military law, which stated that men who could escape were required to try; the same dichotomy existed in German PoW camps holding Canadian PoWs.

There was also an important case precedent that would have bolstered the defence’s appeals, although its counsel (and perhaps the Crown) were unaware of it. Earlier in the war, a South African judge had recognized the unnatural environment of a prisoner-of-war camp and refused to invoke the death penalty in the case of two German PoWs who had killed a fellow prisoner they believed was a traitor.

That judge determined that, while the accused had committed an offence according to South African law, they were under orders from their own government to kill traitors in their midst. There was “a grave risk” that they would be regarded by their fellow prisoners as being guilty of conduct prejudicial to military discipline had they failed to act. And so the judge sentenced them to five years of hard labour.

Canada was aware of the case because the two accused PoWs had been transferred to one of its camps after the killing in South Africa, and had to be shipped back to stand trial. Had the Crown been apprised of the case, it may not have sought the death penalty in the Lehmann trials. Had Howson known of it, he might have conducted himself differently. And had the juries known that another common-law jurisdiction had effectively accepted the argument that a PoW was not free to refuse an order, they might have recommended mercy for the accused.

Two other cases – one that was contemporaneous with the Medicine Hat trials, and one which came days after the end of the war – would have offered insight, too.

The first was that of Kanao Inouye, who was born in Canada but was studying in Japan when the Second World War began. As the son of a Japanese father, he was drafted into Japan’s army and stationed at a PoW camp in Hong Kong, where about 1,750 Canadians soldiers were held. Inouye was tried before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East for viciously assaulting a member of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, among several other war crimes. He was convicted and sentenced to hang.

However, the commander of the military district ruled that as a British subject (as all Canadians were until the 1947 Citizenship Act), Inouye should not have been tried as a foreign national. So he was tried again – this time for treason. Even in Japanese-occupied Hong Kong, he owed a fealty to the British Crown.

Inouye’s situation was analogous to that of the four defendants in the Lehmann killing. They were German citizens who had sworn an oath of personal allegiance to the Fuhrer, just as a British subject, Inouye, was assumed to be loyal to the Crown. If Inouye’s presumed allegiance to King George VI trumped the metropolitan law that assigned his allegiance to Emperor Hirohito, then the Medicine Hat defendants’ allegiance to Hitler and to Germany’s military code should have trumped the metropolitan law of the criminal code of Canada.

The other case involved the First Canadian Army in Holland, which demonstrated a more practical application of the principles of military justice to PoWs. Though the German forces occupying part of Holland had surrendered to the Canadians, the Germans were left in place until the Canadians could move in an occupation force. Shortly after Germany’s surrender, the Dutch Resistance handed over two German naval deserters, whom they had been safekeeping, to the Canadians.

Within hours, the Canadians passed them along to Germany. A German military tribunal was promptly scheduled. The two were found guilty of desertion, and sentenced to death by firing squad. The Canadians supplied the eight rifles and 16 rounds the Germans had requested to carry out the sentence.

V-E Day celebrations in Toronto, 1945.The Globe and Mail

Much is made of Canada’s valorous service in the Second World War, and rightly so. About 45,000 courageous Canadians died in the hills of Hong Kong, perished on the stormy North Atlantic, fell from the skies over Europe, and were killed or mortally wounded on the beaches and fields of Italy, France, Holland and Germany.

Every one of the scores of men and women I interviewed for my books on Canadians who fought in the war told me that, even generations later, they knew with every fibre of their being that they had fought against evil, for fairness and to make a more just world – one in which Canada and its institutions would be safe.

Their efforts and pain, as well as their comrades’ supreme sacrifices, were not in vain. Their blood, sweat and tears are not diminished by the miscarriage of justice suffered by the killers of Plaszek and Lehmann. Rather, the world the veterans bequeathed us allows us to see it for what it is. Let us not look away.