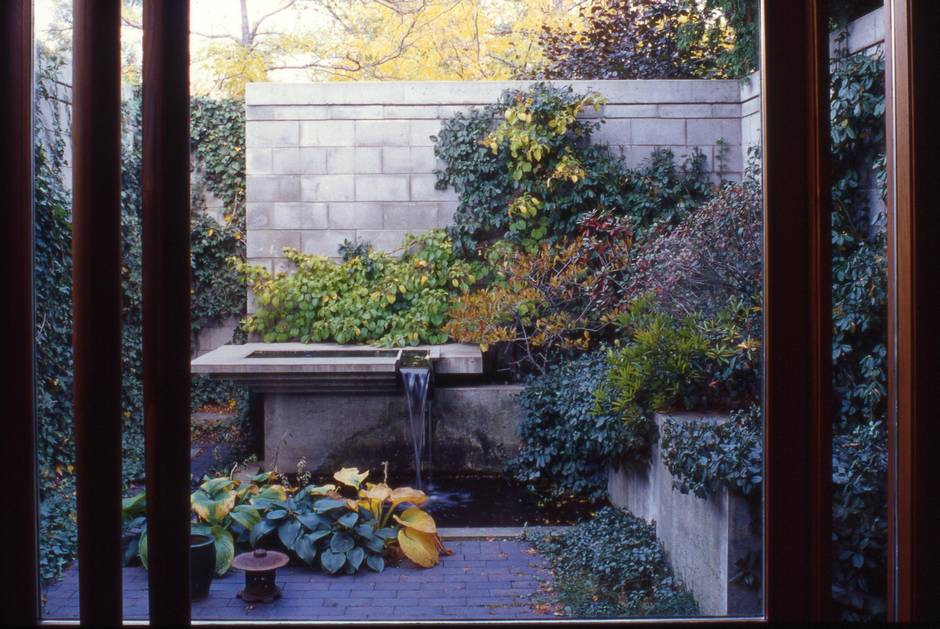

It was a warm day, and the burbling of a little waterfall carried on the breeze. Ivy and rhododendron rustled, and birds chittered in the trees above us. We could have been deep in the suburbs, but Brigitte Shim and I were sitting in a back laneway in Leslieville.

At her kitchen table, to be precise, in the exquisite little house that the architects, Ms. Shim and Howard Sutcliffe, built in 1993. They settled here, between neighbours’ garages and a gas station, over the strenuous objections of city planners. And they still live here, in 1,350 square feet, with their two sons. “It was an experiment,” Ms. Shim says. “We never thought we’d stay here this long. But it’s now the perfect size for us.”

This little house embodied a big idea: to take some of the scruffy territory in Toronto’s 300 kilometres of laneways and put it to better use as homes. And after 20 years, the city is now ready to look at “laneway suites.” A community group, Lanescape, is pursuing the effort with support from the urbanism and sustainability group Evergreen and city councilors Ana Bailao and Mary-Margaret McMahon. A public consultation will happen at the Evergreen Brick Works Dec. 5 and Ms. Shim will be speaking about her experience.

Can laneway housing work in Toronto? It can. Ms. Shim and Mr. Sutcliffe’s experience teaches us that – and their experience also shows that Toronto should be much more courageous in allowing change to its neighbourhoods.

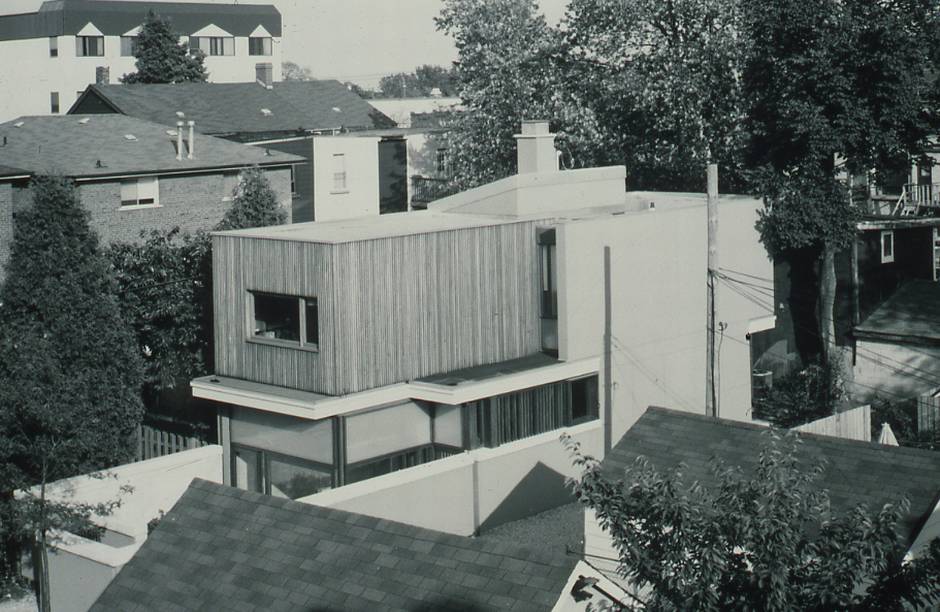

While they were just launching Shim-Sutcliffe Architects – today one of Canada’s most decorated architecture firms – the couple fought to make their own change to the city. First they bought “a junker lot,” as Ms. Shim puts it; a landlocked rectangle just 17- by 45-feet in the middle of the block near Queen and Leslie, clogged with abandoned cars. Then they purchased three more lots, “stitching them together to form one the same size as a regular lot,” a north-south strip in a block where the neighbouring lots run east-west.

But that was the easy part. The biggest challenges were getting services in to the lot, and then getting planning permission. A local city planner was worried – truly worried, as Ms. Shim recalls – about the young couple: “He said our quality of life would be ruined living in a lane,” she says ruefully.

Why? Privacy. Noise. Smells. Somehow this place, smack in the middle of a residential neighbourhood, seemed to the planner like a profoundly inappropriate place to live – a place that would make them miserable.

He needn’t have worried. Ms. Shim and Mr. Sutcliffe are profoundly talented architects, and they put years of effort into this place. It shows. The walls are made of concrete block, and the house is in many ways modest. There are just two bedrooms, a bath and a small office upstairs. Yet the house is pierced by a skylit central stair lined with glimmering walls of Venetian plaster. The windows framed in mahogany add to the sense of quality and solidity. It sings.

Now, if the city adopts new regulations, a “laneway suite” will probably be an inexpensive apartment on top of a garage, and not a boutique house like the Shim-Sutcliffe’s. But what makes that house so magical is the design and the site. Contrary to the planner’s worries, you don’t feel hemmed in here; in fact from the main rooms, you can’t see anybody at all. Ms. Shim and Mr. Sutcliffe dropped the house’s main floor below ground by three feet, and the garden even lower to five feet below ground; this changes your perspective so that you can’t see anything beyond the garden wall.

Sadly, the architects had to devote a lot of their energy to haggling about zoning: after being refused development permission by the city, they took their proposal to the Ontario Municipal Board, and won. (The OMB is notorious among Toronto progressives for overruling city planning decisions; sometimes that has been a good thing.)

The funny thing is that Ms. Shim and Mr. Sutcliffe didn’t invent this idea. As Toronto grew rapidly and messily from about 1870 to 1930, there was nothing to stop people from settling in laneways, or setting up shop there. Workshops, lumberyards, and later garages were scattered through the lanes – and houses too, on a handful of streets including Croft Street near College and Bathurst.

This history has been thoughtfully documented. Ms. Shim and her colleague Donald Chong edited Site Unseen, a book on the subject, in 2003. That same year the late Jeffrey Stinson, together with colleague Terence van Elslander, wrote a study for the Federation of Canadian Municipalities on the topic. They estimated that laneway housing could increase the number of housing units in the old city of Toronto by 5- to 10-per cent – roughly, between 6,000 and 12,000 units total. That would not affect housing affordability, but it would give people more choices.

Ms. Shim, now a professor at the University of Toronto and a member of Waterfront Toronto’s Design Review Panel, continues to believe strongly in this premise – and that other forms of new development are needed. “This is a city that needs different ways to densify,” Ms. Shim tells me, as the sun dances across the grain of her dining-room table. “If we only have houses and then 54-storey projects, then people don’t have choices about how to live. And we need choices.”

Yet laneway housing in Toronto has stalled for many years, despite a few one-off projects. The City of Toronto’s planning department studied the idea in 2006, and imposed so many conditions on laneway sites that they remained effectively unbuildable. The issues: How do people find the place? How do emergency services reach it in an emergency? Who takes out the garbage, and where?

All of these issues are solvable, if you want to solve them. In fact they have already been solved as the city deals with the exceptions that already exist.

The real problem is cultural. In neighbourhoods such as Leslieville, the lowrise Victorian and Edwardian blocks that surround the downtown core, there is a widespread feeling that the fabric of the city should not be touched. This idea goes back to the 1970s, when progressive activists, planners and politicians were defending these areas from being redeveloped with highrise towers.

They won: ever since 1976 these neighbourhoods have been largely protected from development. In the city’s current official plan they are classed as Neighbourhoods – capital N – and it is very difficult to build anything other than a single house or duplex.

Meanwhile, Ms. Shim went to advise the City of Vancouver’s planning department about laneway housing, and that city went ahead with new regulations. Two thousand laneway dwellings have been built in Vancouver.

“Toronto,” Shim says dryly, “has not been visionary.”

In the early 1990s, few people could imagine that living in a laneway would be a reasonable choice. But few people would have imagined that middle-class neighbourhoods would become inaccessibly expensive. In 2016, it’s time to think differently.