Canada's federal finance minister, Joe Oliver, said that Ontario’s lagging economy was holding back Canada’s potential. “You just have to look at the numbers”, he said Monday.

A look at the numbers on job creation -- the focus of every party’s promises during the provincial election campaign – reveals two things: Ontario isn’t holding Canada back, and job creation isn’t just a numbers game. If you want to get out of the deficit woods, pay attention to the kind of jobs being created.

Far from being an economic laggard, Ontario has been second only to Alberta in terms of the numbers of jobs created.

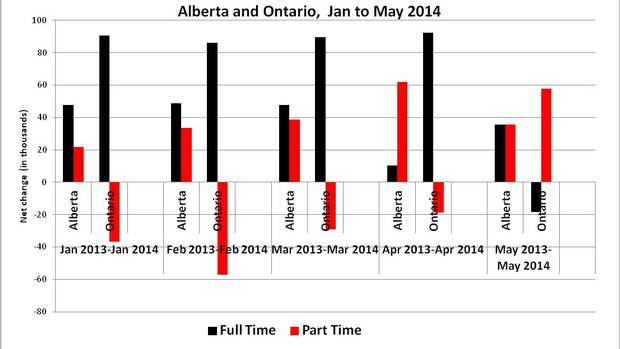

In fact, so far this year, Ontario has created more full-time jobs than Alberta.

Over the past year, Alberta has created more jobs than Ontario, but has seen faster growth in temporary positions than permanent ones. The opposite is true for Ontario.

In May 2014, 14.4 per cent of the jobs in Alberta were temporary, compared to 9.9 per cent in May 2009, during the worst of the downturn. In Ontario almost one in eight people (12.7 per cent) held temporary jobs in May. In addition, a growing share of Ontario’s workforce relies on minimum wage jobs.

Ontario’s labour market took a serious beating in the 2008 global economic crisis, but both the downturn and its rebound were quicker than in the 1990s.

Today the number of jobs created brings us 4 per cent past the pre-recession peak, though many jobs are not as well-paid or stable as the ones lost.

More young people are sidelined now than in the depth of the crisis. New plant closures keep gnawing away at Canada’s shrinking industrial base. Lose a good job with benefits, and good luck finding another. With so many people walking on eggshells, this election’s focus is on job creation first, not deficit reduction.

Cue the promise of a million new jobs for Ontario. The Progressive Conservative Party's plan to grow the job market starts by cutting 100,000 public sector jobs (equal to 60 per cent of the job loss endured by the province in 2009).

Forget the crazy math. Just look at the trends.

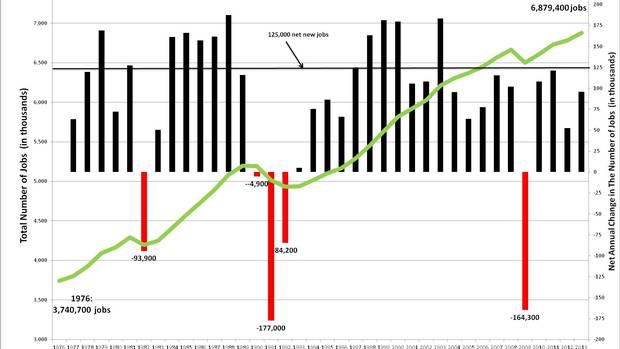

Expanding Ontario’s labour market by a million jobs requires adding 125,000 new positions every year for the next eight years. Is that doable?

The closest we came to that pace of expansion was a generation ago. From 1976 to 1986 a million positions were added to Ontario’s labour market, growing the labour force from 3.7 to 4.7 million, including time out for a recession. Unemployment rates rose, but so did the employment rates of women.

That period of sustained job growth was because of a big shift, from Monday-Friday 9-5 jobs being the norm to more part-time and just-in-time hiring. The rate of job creation has slowed with each passing decade, as has the rate of growth of the labour force. That’s part productivity, part demographics.

There are almost 7 million people with paid jobs in Ontario today. How many of these jobs will disappear with the retirees? Job-cutters like to say attrition is a painless way of reducing payroll costs (to maximize profits or minimize deficits). But fewer people working means less income to buy things and pay taxes for services.

That’s why Ontario’s deficit grew unexpectedly in 2013-14: Two unforeseen drops in revenue came from lower personal income taxes (household income grew more slowly than forecast); and lower sales tax revenues (less income means less shopping, means less HST).

More retirements will mean slower income growth and less spending. Will job creation trends reinforce or offset this trend?

It`s not just the number of jobs being created that matters; it`s also the types of jobs being created. Jobs are always being created and lost. Are the replacement jobs more often full- or part-time; permanent or temporary; paid a living wage or better, or paid at the lowest rate laws will allow?

Changing labour markets can produce economic and fiscal drag. That -- not crafting questionable assertions designed to influence the outcome of a provincial election campaign – should be occupying and concerning Canada's Minister of Finance.

Armine Yalnizyan is Senior Economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. You can follow her on Twitter @ArmineYalnizyan