Cans of Moosehead Lager showcasing its original logo wait to be shipped from Saint John, N.B.

James West/The Globe and Mail

Want to interact with other informed Canadians and Globe journalists? Join our exclusive Globe and Mail subscribers Facebook group

As with any neighbour you've known for years, New Brunswick is on a first-name basis with its beer. Here, it's just Moose – Moose Green for the lager, and Red for the original Moosehead beer, even though the ale no longer has a red label.

But that doesn't mean they always drink the beer from Moosehead Breweries Ltd. At a pub in uptown Saint John, a lager order goes through without a hitch, but when asked for the ale the bartender hesitates. Instead, he pours a taste of a pale ale from a Fredericton craft brewer, Graystone, to compare with a taste of Moosehead's ale.

"Moose Green, I love it. I drink it like it's going out of style," he says. But pointing to the two glasses, he insists, "You can just tell one is a domestic" – a bigger brewer – "and one's not."

This is Moosehead's problem. For the growing number of people gravitating to craft beer in search of new flavours (or just a cooler-looking label that will confer a bit of hipster status), it's too big to love. And outside of its home turf, the situation is even worse.

"'You guys are owned by Molson, aren't you?' That's a consistent piece of feedback," says Trevor Grant, vice-president of sales and marketing at the independent, family-run brewery.

More than 1,200 kilometres away, on a craft-heavy pub menu in downtown Toronto, Moosehead lager is listed under "Macros and imports we don't hate." This kind of grudging respect is about as good as it gets for a big-ish brewer these days.

Moosehead is indeed a macro compared to the newest players on the beer scene. There has been a boom in licensed breweries in Canada – reaching 644 last year, a huge jump from 290 just seven years earlier – driven largely by operations producing less than 2,000 hectolitres (200,000 litres) per year, according to Beer Canada. (Moosehead contributed too, opening the Hop City craft brewery in Toronto in 2009.)

But while Moosehead is bigger than those upstarts, and is the fourth-largest brewer in Canada – behind Molson, Labatt and Sleeman – it is a distant fourth. The big two have more than 75 per cent market share of beer sales nationwide. Moosehead has 2 per cent to 3 per cent.

The company draws roughly $200-million in annual revenue – a number that has stayed relatively flat for at least eight years, though the makeup of the business has changed: it is selling more of its own beer and beers it distributes in Canada such as Boston Beer Co.'s Sam Adams. That has made up for losses in its contract brewing business – most notably when it lost the Guinness account a few years ago – and the steep decline in its U.S. sales amid the explosion of competition from both craft beer and imports there.

The Oland family has been managing these business challenges all while grappling with personal tragedy: the brutal murder in 2011 of Richard, brother of the chairman, Derek, and uncle of the current CEO. With the accused, Richard's son Dennis, awaiting a second trial, they will not be able to put the ordeal behind them for some time, even as professional demands loom.

Andrew Oland, president of Moosehead Breweries, left, and father Derek Oland, check on the operations of the packaging line.

James West/The Globe and Mail

Moosehead needs to grow. To do that, the leaders believe they need to tell their story as an independently-owned operation as old as Confederation. Sure, it has emphasized its conveniently patriotic founding date – 1867 – on packaging and in ads for years, but without the money to wallpaper its brand across consumers' field of vision, and lacking some consistency from one ad campaign to another, the message hasn't really stuck.

Meanwhile, competitors with deeper pockets have been freely, and some might say dubiously, riding the wave of Canadian heritage. Molson Coors Brewing Co. – now a multinational – trades on the slogan " I am Canadian"; and Sleeman, now owned by Tokyo-based Sapporo Breweries Ltd., has used its ads to romanticize its "shady past" selling beer during Prohibition in Guelph, Ont.

"Here we are, 150 years old, and we're still just getting started in Canada," says Moosehead president and CEO Andrew Oland, who with his brothers, is among the sixth generation managing the company. "We just have to tell our story in a way that is genuine to us. We think we have an authentic story."

Handout/Moosehead

In 19th-century England, brewing – like cooking – was often a woman's job. Susannah Oland carried the skill for brewing from England to Canada when she and her husband John immigrated. Unusually, it was the matriarch who was the driving force behind the company founded in Dartmouth, N.S., in 1867, selling her backyard brew, October Brown Ale.

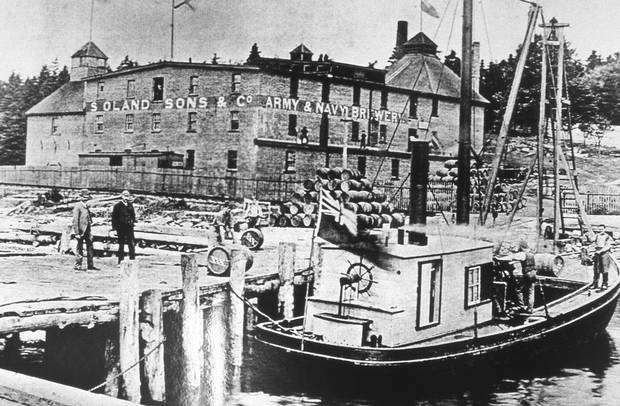

The company was not called Moosehead then. It was first the Army and Navy Brewery, named in recognition of Halifax's status as a naval port, and later S. Oland, Sons & Co. The "S," the family believes, was an attempt to de-emphasize the woman behind the operation.

Since the beginning, two forces have seemed to stalk the company now known as Moosehead: in-fighting, and disaster.

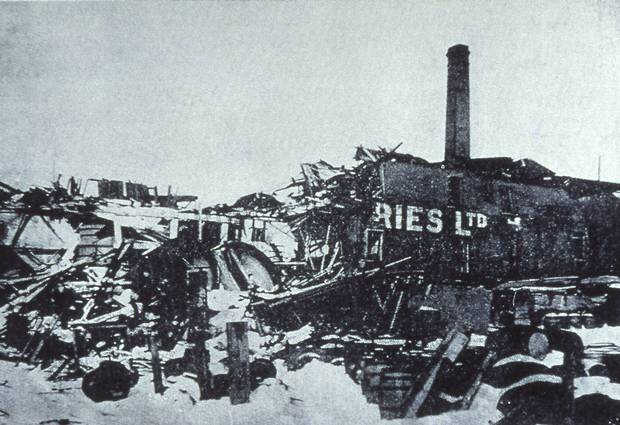

The latter struck repeatedly in its early days: the Dartmouth brewery burned down in 1878; was rebuilt and then burned again in 1896. Fire hit the family's house next door in 1905. Fires weren't unusual in those days, with brewery kettles heated over open flames. Moosehead, as it's known now, might never have existed if it weren't for a much greater disaster: the Halifax Explosion. That day in 1917, Susannah's son Conrad and six other employees died in the destruction of the Dartmouth brewery. Derek Oland, the company's executive chairman and father of the current generation of managers, remembers his father P.W. telling stories of the sound of the blast, the windows of his schoolroom shattering and the sight of dead horses on the road on his walk home that day.

The brewery levelled by the Halifax Explosion.

Handout/Moosehead

While the Halifax operations were rebuilt, the family branched out to New Brunswick, buying the Red Ball brewery in Saint John. A decade later, they bought the James Ready brewery – where the beer is still brewed today, in a building dating back to 1886 – and in the files there, they found a registration for the name "Moosehead." Moosehead Pale Ale was launched in 1933. In 1947, the company was renamed Moosehead Breweries Ltd.

But the family was plagued by other problems – with each other.

In-fighting dates all the way back to Susannah's son and successor, George W.C. Oland. When he died, he left each of his sons a brewery, each with vastly different fortunes – a recipe for resentment – and all of which competed with one another. According to the book Last Canadian Beer by Harvey Sawler, Sidney Oland got the largest operations in S. Oland & Sons and the Keith's brewery back in Halifax, as well as just over one-fifth share of New Brunswick Breweries (later Moosehead). George Bauld got the rest of that operation in Saint John. Geoffrey was left the Red Ball brewery in Saint John, the smallest, which Sidney would later buy in order to compete with George Bauld on his turf. In retaliation, Moosehead opened a plant in Dartmouth; and then Sidney opened yet another brewery in Saint John. This corporate version of a sibling slap-fight would continue until the Halifax branch of the Olands sold out to Labatt in 1971 for an estimated $12-million.

George Bauld's son P.W. would repeat his grandfather's mistake in clumsy succession planning – in his case, dawdling over the choice of which son would take over. It didn't help that Derek and Richard Oland had never really been close as brothers, let alone as colleagues.

"Dick and I just didn't agree. He had his way of doing it and I had mine, and Father couldn't make up his mind," Derek said. "…That schism between us, you can't have that."

In 1980, Derek resigned. P.W. coaxed him back with a promotion. Dick, reading the tea leaves, left. Derek became president in 1982.

He has been more cautious about succession planning, buying back the shares from his brother and sister in 2007 to consolidate ownership. He is now in the process of meting out those shares to the next generation. Derek also handed the CEO role to two non-Oland executives, until he felt his son Andrew was ready. Derek has required each of his sons to work elsewhere before pursuing a career at Moosehead – a policy Andrew plans to uphold – and insists they were free to choose other jobs, as their brother Giles has done. Derek and his wife Jackie worked to foster respect between the boys – something that had been missing between Derek and Dick.

"I'd make up with him," Derek said in the 2009 book Last Canadian Beer by Harvey Sawler. Derek now says he and and his brother were in a good place before tragedy struck the Oland family in 2011.

Dick's bludgeoned body was discovered on the floor of his office. His son Dennis was the main suspect.

"We are convinced, absolutely convinced, that he had nothing to do with it," Derek says. "He's an innocent man that happened to be the last known person to have seen my brother. But we know that he wasn't the last person. So what we are doing is we are defending him and supporting him in every way we can. It was not well investigated."

Dennis was found guilty of second-degree murder in 2015. The New Brunswick Court of Appeal overturned the conviction last October, but a new trial is not expected until at least 2018.

"I wouldn't wish this on my worst enemy," says Derek. "What it does to your family. Just terrible stuff."

A huge, handmade dewdrop-shaped copper kettle lends some nostalgia to the Moosehead brewhouse, but not much function. It sits beside a large old console covered in dials, lights, and diagrams of the brewing process. All that work is now done on a laptop, and in the stainless steel equipment on the other side of the room, which smells sweet and grainy from the most recent batch.

"They don't have that beauty," Karen Cousins, Moosehead's director of communications, says of the steel vessels. The old stuff is for show. "People love looking at them."

But there haven't been too many people through here in recent years: the tour of Moosehead that Ms. Cousins is leading today does not happen often. It's something the company hopes to change. This cruise season, 144,000 passengers and 57,700 crew will come through Saint John's port – arriving in a city with plenty of charm but a limited number of tourist attractions. Brewery tours could be an opportunity to remind people of Moosehead's independence, and its heritage.

Bottles of Alpine Lager move on the packaging line.

James West/The Globe and Mail

It's one part of a broader marketing effort. An ad campaign launching this spring for the 150th anniversary will link the brewery's past with key moments in Canadian history. The family wants to launch more brews under the Moosehead brand umbrella, and is considering digging into the archives to revive some heirloom recipes.

On carts in the brewery sit bags of fragrant hops destined for the company's new limited-edition "Anniversary Ale." Like many beers brewed here, most of Moosehead's ingredients are Canadian – the grain, the water, the yeast it grows in its on-site lab – but hops are harder to come by locally, particularly at the scale that a relatively big brewer needs.

"They cleaned me out of the two major varieties I grow," says Veronica Paul, who runs the conveniently-named Moose Mountain hop farm in Maplehurst, N.B.

"People just know us for Moosehead lager. We wanted [this ale] to be a step forward, telling people about our brewing credentials, and doing it in a bit bolder style than maybe people are used to from Moosehead," marketing head Mr. Grant says.

But credibility is a funny thing. Moosehead is caught in the middle. Even with the rise of craft beer, the vast majority of beers quaffed in Canada are still blonde lagers. For Moosehead, experimenting with new brews is a way to give the flagship brand a more "premium" image – to make its easy-drinking lager more attractive on a store shelf than other easy-drinking lagers such as Bud or Molson.

Moosehead is already making craft beer. It owns Hop City, the brewery behind brands such as Barking Squirrel and Hop Bot IPA. In January, it abandoned a plan to build a new small-batch brewery in Saint John, but still plans to build a facility that will allow it to make more experimental beers.

"My personal opinion is, everything should be under Moosehead – it's a strong brand," says Craig Pinhey, a Saint John-based sommelier and beer writer. "In other countries, they think of it as a premium brand, not only as mainstream. It's only here that we think of them as mainstream."

A lab technician pours Moosehead Lager into a filter system as part of the degassing process.

James West/The Globe and Mail

Lagers may taste light, but they are deceptively hard to make because there is nowhere to hide: unlike a hoppy IPA, a lager has no strong flavours to mask imperfections.

Moosehead has a handle on that quality, but lacks some of the complexity of flavour of European counterparts such as Pilsner Urquell, says beer writer Stephen Beaumont.

"The parallel story to them in a lot of ways is Yuengling, the oldest U.S.-owned brewery," Mr. Beaumont says.

"Yuengling has built an almost cult-like following, and they're not doing a whole lot different – you could argue that Yuengling lager is a little bit more evolved than a Budweiser or a Coors Light, but essentially they've positioned themselves as a niche label rather than a niche beer. Moosehead has been trying to do that, with varying degrees of success."

That kind of heritage-based loyalty could give Moosehead a boost in its planned expansion across Canada. Forty per cent of its sales come from Ontario, a market where the company did not sell a drop 25 years ago. New Brunswick and the United States count for roughly 20 per cent each. The remainder comes from a mix of international sales in about 15 countries, and the rest of Canada combined. That's a lot of untapped territory, especially in the West.

"Outside of Molson and Labatt, no one – Sleeman is close – no one has a full Canadian business across all 10 provinces," Andrew Oland says. "That's what we're trying to achieve."

The sixth generation likens the importance of this project to their father's expansion into the United States in the 80s – Moosehead went south before it went west, largely because of the patchwork of provincial regulations complicating alcohol sales across Canada.

The U.S. push forced the company to invest in modernizing its operations. It was the debut of its familiar green bottle, chosen because Americans equated the green glass with other premium imports such as Heineken.

Ironically, despite the premium image the green glass is worse for the beer because it lets in more light. The company says as long as they are shipped in closed cardboard and stored in the dark rather than light-up beer fridges it should be fine. It led to the design, by a professional, of the current Moosehead label. Before then, Derek's father P.W. drew many of the designs himself, including the original moose. And it was the birth of the slogan, "The Moose is Loose," which has never been Derek's favourite.

"You can't laugh at the moose," he says. "If you do, you're laughing at yourself. It's a majestic animal that roams the woods of most of Canada, and it says what we want about our company."

Moosehead succeeded in building a premium import image, and saw incredible growth in the United States – reaching 26 states in the first year alone. Eventually, though, Moosehead was unwilling to compete on price and did not control its own distribution – all as competition heated up.

"It's probably one of my biggest disappointments," Derek says.

Now, Moosehead is looking to Canada for its next phase of growth, and it believes that its independence could be a selling point.

"You have to buy yourself out every generation … bringing the shares back to one or two or three individuals," Derek says of the control that has helped the brewery stay independent. They have had plenty of offers. "If we wanted to sell, people could be killed in the rush," he says. "It's a joke – but we know this place wouldn't be the same. It would be a branch plant, at best."

None of the seventh generation currently works at Moosehead. Andrew's children are all in their 20s, but the rest are much younger. "We're not going anywhere for a while," Andrew says. "It's not my job to tap [the next generation] on the shoulder. It's their job to initiate the conversation." Still, he acknowledges that while it's possible someone outside the Oland clan could once again lead the company – not least because it helps to recruit talent if a surname is not a requirement for advancement – but that would not be ideal in the long term. "We would like to see Moosehead continue to be a multigenerational family business," Andrew says. "I think you can have non-Oland leadership for a period of time, but you can't have it forever, because then I'm not sure it's really a family business."