These players in the $3.3-billion space industry are already blasting off

1. Neptec - Kanata, Ontario

Only a dozen men have ever set foot on the moon – the last ones, Jack Schmitt and Eugene Cernan, in 1972. But a group of international

space agencies, including NASA and the Canadian Space Agency, have brought up

the possibility of laying the groundwork for an eventual human base on the lunar

surface.

Hauling enough water and other resources to sustain life on the moon, though, is prohibitively expensive. According to NASA, it costs $10,000 to put one pound of payload into Earth’s orbit–and exponentially more to shuttle it 384,400 kilometres to the moon. So, in 2018, NASA and its partners hope to launch the Lunar Resource Prospector mission, to map water and other resources on the moon.

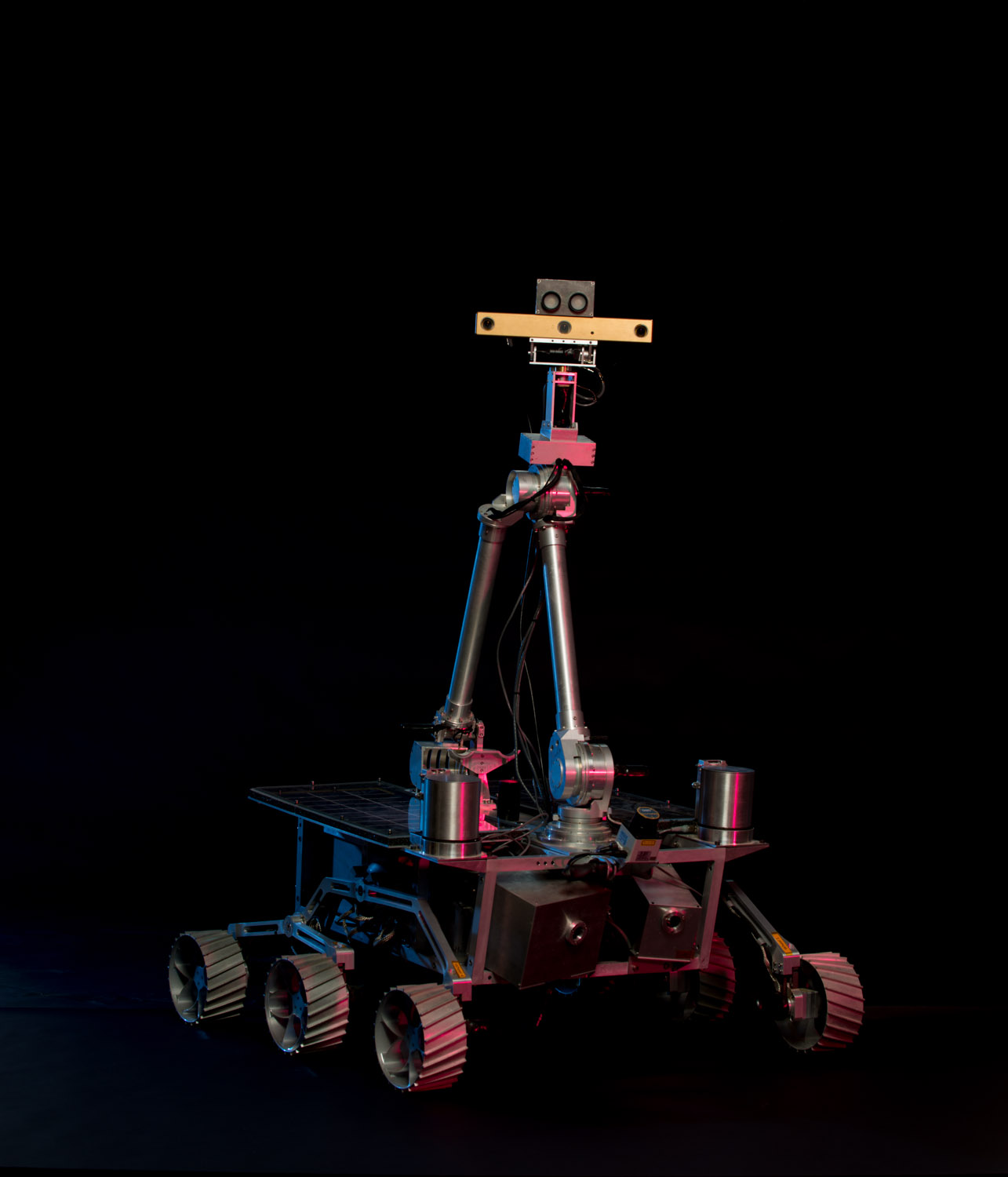

The Artemis Jr. rover, a 270-kilogram unmanned robot designed and built by Neptec Technologies, is a key part of the project. Its job will be to drill for and collect samples to bring back to Earth (Neptec partnered with Sudbury-based Deltion Innovations, which builds drilling systems for primarily Earth-bound mining companies). To ensure that Neptec’s remote-controlled rover can get the job done, the Artemis Jr. has endured rigorous testing on the slopes of Hawaii’s Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano whose surface closely resembles that of the moon.

Neptec, which has 65 employees at its facility just outside Ottawa, is not a newcomer to space. In the mid-1990s, its breakthrough technology, the Space Vision System, helped astronauts assemble the International Space Station (ISS) and is still in use on Canadarm2. Neptec’s laser sensor technology, employed on the Artemis and in the TriDAR system it designed for docking the Cygnus resupply vehicle with the ISS, is now being used by mining companies to lend precision to the routes of massive open-mine dump trucks. That’s the key to surviving as a small space contractor, says Neptec’s president of space exploration, Mike Kearns: putting the technology you design for space missions to work here on Earth. Ontario Drive and Gear (ODG), which designed and built the Artemis chassis and drivetrain, has started incorporating some Artemis components into its commercial electric-powered vehicles. Kearns, too, has plans for the Artemis Jr. technology. “The U.S. military is having to cut back on the number of soldiers, and one of the ways to do that is to have a fleet of autonomous vehicles,” he says. “There’s an opportunity there. It’s something we’re going to pursue.”

In the meantime, Kearns’s team at Neptec is preparing for its first mission to Mars, also slated for 2018, when the red planet will be just 57.6 million kilometres away from Earth. The company has signed a deal with U.K.-based Astrium to put navigation cameras on the ExoMars rover, part of a mission funded by Russia and the European Space Agency. /Shane Dingman

Update

2. L-3 MAPPs - Montreal

For the select group of 100 international astronauts who have earned the

right to operate the Canadarm2 –

a group that includes Canada’s own Chris Hadfield – there is no such thing as winging it.

Before a crew member aboard the International Space Station performs a delicate

manoeuvre like docking capsules full of crucial supplies, each minute move has

been rehearsed ad nauseam back

on Earth.

Their training begins at a Canadian Space Agency facility in Saint-Hubert, a suburb just east of Montreal. There, the CSA uses a simulator built by L-3’s MAPPS division to teach astronauts how to control the device that is synonymous with Canada’s pride in the space program (it is even emblazoned on the new $5 bill). At $1-million annually, the Canadarm2 simulation contract is a drop in the bucket for L-3 – an agglomeration of roughly 100 divisions with sales of $12.6-billion. But since taking over the contract from CAE Inc. 15 years ago (after acquiring the CAE unit that originated the program), L-3 has scored a simulation contract for the European Galileo GPS system, too.

The Canadarm2 simulator itself is somewhat underwhelming – just three small monitors and a control panel rigged up against a phony background and housed in a warehouse-type space. But it contains the only software in the world that can prepare astronauts for the nervy 90 seconds it takes to grab a floating unit (plus a few more hours to dock it), or teach them how to support their comrades on sorties outside the International Space Station. With every change to the station, the otherworldly simulator software is tweaked and upgraded, a full-time task for a small team of L-3 MAPPS employees.

Meanwhile, across the hall from the training facility is an off-limits office manned round the clock by CSA technicians. In there, they manipulate between 80 per cent and 90 per cent of Canadarm2’s manoeuvres – the less delicate grunt work that can be handled from Earth. /Kristian Gravenor

3. MPB Communications - Montreal

In February, 2013, researchers in Chile aimed a massive yellow laser at the

heavens. The beam that it emitted lit up sodium in the atmosphere as high as 90

kilometres up, creating an ersatz star that helped scientists calibrate the

telescope below. Montreal-based MPB Communications beat out several European

competitors for the contract, and its work on the project made it a world leader

in laser technology.

MPB derives 85 per cent of its $25-million in revenue from far less shiny pursuits, such as setting up fibre-optic phone networks in Mexico. It was launched in 1977 by Morrel Bachynski, a PhD in plasma physics (he attended Montreal’s McGill University) who took over RCA’s old research and development lab. The company is now run by his daughter Jane, who started there as a kid cleaning the warehouse and has been at the helm since her dad’s death in 2012.

Among its 150 employees are a dozen PhDs, in everything from laser physics to robotics. And the company has tight ties to academia. Laser physicist Wes Jamroz, a 30-year veteran of MPB and director of its space division, has forged countless deals with universities over the years that resulted in many of the company’s breakthroughs. A 40-kilogram microrover commissioned by the Canadian Space Agency had its arm built by students at Ryerson University, and its chassis at Carleton (the prototype is still being tested). It could be crawling on the moon by 2018. In concert with Concordia University, MPB created a self-healing system for spacecraft. And its patented smart coating was developed for the CSA in partnership with the Institut national de la recherche scientifique, a graduate and post-grad university in Quebec. It will be applied, using a laser, onto a soon-to-launch European satellite – the coating will prevent the satellite from freezing in space. /Kristian Gravenor

4. Magellan Aerospace - Mississauga

The Black Brant rocket looks like something Wile E. Coyote might strap to his

back. It’s almost cartoonishly simple, with a long, thin,

cigar-shaped body – it measures 46 centimetres across and 5.5 metres long – and fins

at one end. Since the Black Brant first blasted off from Virginia’s Wallops base

in 1962, Magellan Aerospace has manufactured 1,000 of the solid-fuel

rockets.

These aren’t the kind of rockets that would launch Chris Hadfield on a trip to the International Space Station. Though they have travelled as high as 1,300 kilometres (the ISS orbits at about 400 kilometres above Earth), the Black Brant carries small payloads, anywhere from 45 to 450 kilograms. Mostly, they’re blasting up sensors to collect data for scientific research into microgravity, meteorology, and wave and particle mechanics, then falling back to Earth. “There are still things that rockets can do that satellites and the space station can’t,” says David O’Connor, Magellan’s division manager for defence and space products, who oversees a staff of 125, including nine rocket engineers.

The Mississauga-based company builds airplane and satellite components: Two of its most heralded projects are the $2-billion contract to manufacture tail fins for the controversial F-35 Joint Strike Fighter jets and parts for Canada’s three homegrown RadarSat Constellation satellites. Its Manitoba division, meanwhile, builds between 12 and 18 Black Brants each year at a 6,000-acre, 28-building complex just north of Winnipeg. For the past decade, Magellan’s principal customer has been NASA subcontractor Orbital Sciences of Virginia.

Magellan’s current Black Brant design has a record of reliability in the 99 per cent range – not that there aren’t accidents. The first launch O’Connor attended, back in the early 1990s, was a bust. “This was a two-stage rocket,” he recalls. “I remember watching from a grandstand, and a guy on a microphone was saying, ‘There goes the third stage,’ and I knew there was no third stage.” Luckily for Magellan, the failure was caused by the guidance system – built by another contractor. “In the aviation industry, there’s a lot of testing, but in space, we’re craaaazy about testing,” O’Connor says. After all, he says, once you light the fuse on a solid-fuel rocket, you can’t turn it off – and though Magellan refuses to divulge how much one of its Black Brants might cost, you can bet they don’t come cheap. “In this business,” says O’Connor. “if your first one doesn’t work, you’ve failed, and you usually don’t get the chance to make another one.” /Shane Dingman

5. Com Dev International - Cambridge, Ontario

The next time you tune your TV set to the latest episode of The Big Bang Theory, thank Com Dev International. Some 95 per cent of the broadcast TV channels in North America travel through space and back to Earth via Com Dev gear, plus a huge chunk of Internet and cellular signal traffic. All told, the company has supplied key switches, microwave filters and multiplexers for about 80 per cent of the communications satellites ever launched. Bazinga!

Com

Dev was created in 1969. Initially based in

Montreal, the company moved its head office to Cambridge, an hour west of

Toronto, in 1979. It now has 1,200 employees at manufacturing facilities in

Cambridge, the United Kingdom and the U.S., building components not just for

commercial satellite manufacturers, but also for major space agencies and

military contractors. Com Dev has begun

launching its own microsatellites (most recently out of Kazakhstan).

This constellation of orbiting vehicles power Com Dev’s exactEarth network, which tracks the world’s

shipping traffic and sells the data to governments and maritime agencies. Though

exactEarth accounted for just 5.6

per cent of Com Dev’s $215-million in revenue

last year, Com Dev’s CEO, Mike Pley, says the market could be worth as much as

$100-million, of which they hope to capture half.

With Com Dev sitting on $35-million in cash, Pley is on the hunt for acquisitions. His potential targets are other “tier 2” suppliers like Com Dev – but perennial underperformers. Space component contractors are notorious for blowing both budgets and deadlines. After 25 years of working with suppliers and “primes” like Boeing and Lockheed, Pley has seen dozens of companies with great technology but bad processes. As an example, Pley points to Com Dev’s 2008 purchase of defence contractor L-3 Communications’ passive microwave division. “One of the issues at the time was that it didn’t have a high performance in terms of on-time delivery,” says Pley. “They were considered a problem child by some of our customers. Last year, that division had 99.9 per cent on-time delivery. It’s considered one of the top-performing suppliers in that neck of the woods.” /Shane Dingman