Canada has staked its future on the oil sands. In November, Report on Business magazine together with Thomson Reuters examine what that means both at home and abroad. Read more from the issue at tgam.ca/oil.

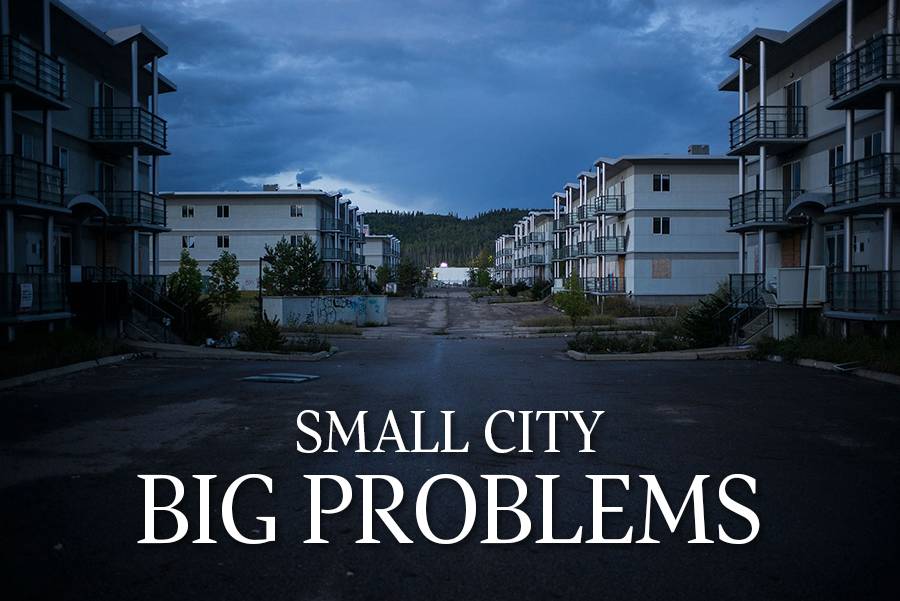

The tenants have long since vacated the Penhorwood condos on the edge of Fort McMurray’s gritty downtown. Engineers declared the cluster of low-rise apartments unsafe more than three years ago, forcing as many as 300 residents out in the dead of night. Nature has since moved in: So much moisture has seeped into the derelict structures that some units resemble terrariums. Paint and drywall are peeling, walls are bruised with black mould, and windows everywhere have been shattered by vandals.

It’s a jarring example of shoddy boomtown construction. But just across the street stands the flip side to Fort McMurray’s blistering growth: a sprawling recreation centre sponsored by oil giant Syncrude Canada Ltd. Nearby, another gleaming complex is going up, festooned with the insignia of European oil major Royal Dutch Shell. Or there’s the $258-million expansion to the regional airport, which opened this summer to accommodate the legions of oil workers who arrive from across Canada and around the world.

Such is life in Alberta’s northern oil capital, a place of supersized ambitions and stark divisions, where boarded-up motels and strip malls rub elbows with trendy restaurants downtown, and new suburban streets are lined with gaudy petro-mansions.

Over much of the last decade, an unprecedented energy boom has transformed the isolated city into a makeshift bedroom community and service hub for workers toiling in the oil fields of northeastern Alberta. The city’s population has exploded, creating a nightmare for municipal planners struggling to deal with a flood of new migrants even as long-time residents cope with infrastructure gaps so wide one official likens the place to a “glorified mining camp.”

The numbers are arresting. In 2006, fewer than 50,000 people called Fort McMurray home. By 2011, the figure had ballooned to about 61,000; today, it’s 116,400. The median age is 31.6, and a “shadow” population of roughly 39,000–some estimates put the number as high as 80,000–lives in nearby camps, exacerbating pressure on everything from the overstuffed hospital to the local Tim Hortons.

About two million barrels of oil a day is squeezed at great cost from the Florida-sized cache of bitumen that lies under the muskeg that surrounds the city and greater Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo. Oil company executives see output doubling over the next decade, leaving many people guessing at who will pay for badly needed roads and infrastructure to support the work.

Kyle Harrietha, the local Liberal candidate for next year’s federal election, ticks off a laundry list of multibillion-dollar expansions planned by global energy companies. Shell, Teck Resources, Suncor Energy, Syncrude and Canadian Natural Resources are all eager to claw more bitumen from the region. “Those things take substantial amounts of equipment, and it’s not fabricated in Fort McMurray,” Harrietha says.

Instead, the massive processing equipment required by the oil sands is built in Edmonton industrial yards and driven 450 kilometres north on Highway 63, a two-lane artery that until very recently had the notorious distinction of being one of the deadliest stretches of pavement in the country. Work is under way to expand the route, which should alleviate some congestion. But the oversized loads still present a problem for locals. “All of that comes straight through Fort McMurray,” Harrietha says. “It puts a lot of stress on the roads.”

Not everything is crumbling. A brand-new airport terminal is a welcome change from the crowded buildings it replaced. But it’s already bursting at the seams. On shift-change days, it’s impossible to find a seat at the departure gates. Almost 1.3 million passengers travelled through the airport last year, including more than 240,000 workers on aircraft chartered by oil sands companies. The expanded facility’s capacity totals 1.8 million passengers, with workers still flying in and out of the old terminal. (Plans call for further expansion, although airport officials aren’t disclosing details.)

The new arrivals include an itinerant population of construction labourers who live for two-week stints in remote camps but come to the city to blow off steam. That has created a rift between those who use city services and those stuck with the bills. Meanwhile, a brisk drug trade makes life for those on the fringe even harder. “We used to really look after each other,” says Mo, one of about 80 homeless people seeking a hot lunch at the Fellowship Baptist Church on a recent afternoon. “Now the dope’s ruined everything.” After a decade of hard living in Fort McMurray, the 59-year-old widow is ready to leave. “The craziest place I ever lived, that’s for sure,” she reflects. “I’d like to get out of here, go someplace warm.”