Just another day on the stump: Kinder Morgan Canada president Ian Anderson prepares to defend his pipeline project during a radio interview in Vancouver.

Ed Ou

A team of public relations reps greets Ian Anderson as he strides into a cheerless café in the Kamloops airport. It is 9:20 a.m. on a drizzly Tuesday in the B.C. city, and the president of Kinder Morgan Inc.'s Canadian operations is getting ready for another day on the stump.

Anderson, a husky man dressed in a dark overcoat, slumps in a chair and nurses a coffee while his handlers run through the day's itinerary. For the past six years, his life has been consumed by his employer's bid to nearly triple shipments of oil from Alberta to the B.C. coast via its Trans Mountain pipeline, so he's become accustomed to the routine. "How do we refer to the traditional territory?" he asks. An adviser pipes up: "Secwépemc." Anderson repeats it, slowly, " Suh-wep-muhc." Later today, he will address the local chamber of commerce, and he's reminded to stick to the prepared script. "Just like Edmonton," a PR woman stresses—implying not like Vancouver, where Anderson caused a minor panic among his staff by suggesting humans are not responsible for climate change. He backtracked, but the company was forced to issue a clarification. "We're not talking about that stuff," Anderson confirms. "It's done. That was yesterday's news."

Two security guards hover nearby. They are at Anderson's side whenever he attends an advertised event, in case protesters show up. "I try to limit it," he says of the protection as he makes his way to an SUV idling in the rain. Still, he adds quickly, "better cautious than not."

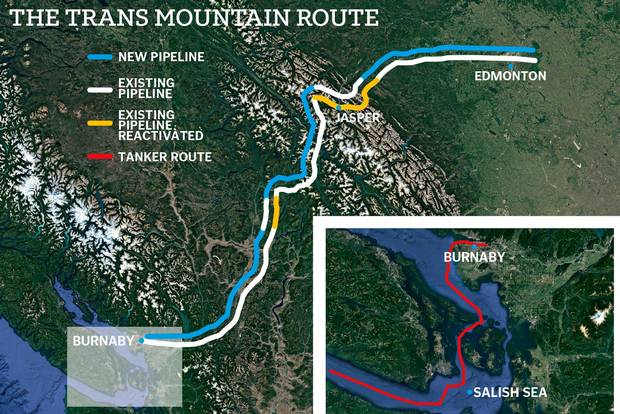

It's a small but telling indication of the charged atmosphere surrounding Anderson and Kinder Morgan as the U.S. infrastructure giant prepares to start construction on what has become one of the most contentious energy projects in Canadian history. Last fall, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau approved the $6.8-billion pipeline expansion, which would nearly triple capacity on Kinder Morgan's westbound system to 890,000 barrels a day. Boosters say the expansion will give Alberta's battered energy sector what it has long sought: wider access to global markets, bolstering prices and breaking a near-total dependence on a U.S. market that's awash in shale crude.

But the project still faces daunting hurdles. Perhaps the biggest is a potent combination of environmental and aboriginal activism that has already been blamed for sidelining Enbridge Inc.'s rival Northern Gateway pipeline. TransCanada Corp.'s Keystone XL also looked doomed until Donald Trump gave it a new lease on life in January. Last fall, opponents temporarily halted construction of the Dakota Access pipeline. For months, Anderson and other energy executives watched with dismay as protests swelled near the prairie town of Cannon Ball, North Dakota, transforming the area into a de facto war zone. Many saw the demonstrations as a dress rehearsal for looming clashes over Trans Mountain. Indeed, federal Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr raised the spectre of a militarized showdown last fall, although he quickly apologized for suggesting the Canadian Forces could be deployed to quash dissent around the project.

Protsets against pipelines, such as those that rocked North Dakota have spread to target Trans Mountain

Ben Nelms/Reuters

Anderson expects crews to start work this fall, but many observers are doubtful. Privately, some industry executives and analysts say it's a coin toss whether Trans Mountain actually gets built, citing court challenges and other obstacles. Kinder Morgan must still satisfy 157 conditions, such as habitat restoration for caribou and offsetting greenhouse-gas emissions associated with construction. That's fewer than Ottawa applied to Enbridge's rival Northern Gateway, reflecting the fact that the Trans Mountain proposal entails building a second pipeline alongside Kinder Morgan's current conduit between Edmonton and suburban Vancouver. This pre-existing pathway gave Trans Mountain a huge advantage over Northern Gateway, whose proposed route, carving through B.C.'s Great Bear Rainforest, enraged environmentalists and coastal First Nations. "You could be the Pope and you'd probably get shot down on that one," AltaCorp Capital analyst Dirk Lever says of Gateway, which the Trudeau government officially killed last fall. While Enbridge's more controversial proposal drew some of the fire away from Trans Mountain, Lever also gives credit to Anderson for addressing critics' concerns up front. "Whatever he did, it was the right formula."

At 59, Anderson has the polished but slightly worn look of a travelling salesman—which, in some respects, he is. Whereas Northern Gateway's backers were criticized for consulting First Nations too little and too late, Anderson estimates he has had 200 to 300 discussions and meetings to date. He has criss-crossed Western Canada pitching aboriginal groups and local residents on the project's economic benefits. It has paid off: As of mid-December, the company had signed agreements with 51 bands, covering the majority of the route. The deals commit Kinder Morgan to providing $400-million worth of employment and financial benefits to those aboriginal groups.

Anderson's latest gambit to secure support is audacious: He has offered to pay the B.C. government as much as $1 billion over 20 years in exchange for environmental clearances from the province, which piled an additional 37 conditions on the project in January. The proposal surprised observers and prompted concern that Kinder Morgan was setting an unwelcome precedent for big infrastructure projects.

The deal has also done little to mollify the pipeline's biggest critics, who fear the consequences of a coastal oil spill and the impact on climate change of oil sands' renewed expansion. These opponents include municipal leaders such as Derek Corrigan, mayor of Burnaby, the Vancouver suburb through which the last stretch of the pipeline would weave. Anderson and Corrigan haven't spoken in four years after the city council formally opposed the pipeline and litigation ensued. Anderson now calls the municipality Corrigan's "fiefdom."

It's one more measure of the rancour that has enveloped the pipeline executive. Being the public face of the contentious project has taken a toll. On a recent evening, after several meetings and a speech, Anderson's voice is hoarse and his eyes are ringed in dark circles. The job "just doesn't turn off," he says wearily, "so you just have to adjust for that."

Anderson has been living and breathing the proposed expansion since at least 2010. But the roots of the project reach back to 2005, when Kinder Morgan paid $5.6 billion (U.S.) to acquire Vancouver-based Terasen Inc. (formerly BC Gas). For the Houston-based company, the jewel of the deal was a small-diameter pipeline built during the Korean War to send burgeoning Alberta oil production to the B.C. coast for export.

The acquisition instantly made Kinder Morgan a player in the fast-growing oil sands of Northern Alberta. To this day, the pipeline is the lone conduit for Canadian oil to energy-thirsty Pacific markets and the big refineries in Washington State. Kinder Morgan seized the potential for growth, initially committing $1.4 billion to expanding Trans Mountain and another Alberta oil pipeline (which it later sold). The investment would provide much-needed infrastructure to support expected growth in the oil sands, enabling the higher-cost barrels "to be more competitive in domestic and international markets," Richard Kinder, the company's billionaire founder, argued at the time.

In Burnaby, Kinder Morgan will tunnel through Burnaby Mountain and lay new pipe under roads near schools and houses. The line will link an expanded storage facility with a new export dock. About 80 killer whales that live in the main shipping channel for crude-carrying tankers are the subject of a federal court case arguing that increased traffic will threaten their survival. Back in 2008, when Kinder Morgan completed its so-called Anchor Loop expansion through Jasper National Park, it encountered little opposition.

Thirteen major oil companies have since signed contracts to ship a combined 700,000-plus barrels a day through the expanded pipeline. The current plan calls for laying nearly 1,000 kilometres of new pipe. About 90% of the new pipeline will follow the existing path or other utility infrastructure such as power lines, the company says. But at its end, a major expansion looms. The company will need larger storage facilities in Burnaby to accommodate the additional volumes. Thirty-four tankers per month could sail past Vancouver's Stanley Park and under the Lions Gate Bridge to the company's Burnaby export dock—up from about five today.

It fell to Anderson to execute this vision, though he initially had reservations about joining the company. An accountant by training, he had arrived in Calgary from Vancouver in late 2004 as a senior finance executive with Terasen. Anderson thought he was an imperfect fit for the top job at the Canadian branch of a company so closely associated with Texas crude. "There was a wee bit of nervousness in that I wasn't an oil guy," he says, seated in a boardroom at the company's Calgary offices during a rare lull in his schedule. "I hadn't spent my career in Calgary in the oil patch."

Anderson grew up in Winnipeg—a print by Cree artist Ernie Scoles at the Calgary office hints at his Manitoba roots—with no particular affinity for the energy business. After graduating from the University of Winnipeg, he took a regulatory position with Greater Winnipeg Gas. "It was a job at the beginning," he says with a shrug. A big part of his role turned out to be steering the expansion of natural gas service to remote communities. That led to a role as VP of finance and regulatory affairs with Centra Gas—later bought by BC Gas—as it expanded service to Vancouver Island. At the time, natural gas was new to the island, and Anderson faced considerable bureaucratic and financial challenges. But he relished the opportunity to build a nimble operation within the confines of a heavily regulated power system.

Living and working in Victoria for three years, and later in Vancouver, gave him a crash course on the political and cultural forces at play on the West Coast. He learned about the varying, and at times competing, interests among municipal governments, First Nations and environmentalists. For example, he says the lack of municipal amalgamation around Greater Victoria complicated efforts to build infrastructure as companies had to deal with multiple local city councils.

Another lesson was more subtle but equally influential: Just about everyone had a kayak. "Everybody I worked with and around me had this connection to the outdoors and the ocean," Anderson says. It made a lasting impression on the native of landlocked Winnipeg, helping to shape his understanding of a region that in some corners remains staunchly opposed to oil-laden tankers plying the waterfront. "I think you can appreciate it from afar, but it certainly doesn't hurt to have experienced it directly," he says. To overcome such deep-seated reservations, he realized he would need to appeal directly to residents of tiny communities from Alberta to Vancouver Island.

Anderson at the Tk’emlups town hall in Kamloops in December

Trans Mountain Expansion Project

At times over the past four years, Anderson's schedule has resembled an old-time political barnstorming tour. Over several days last fall, his itinerary included stops in the Paul First Nation and Enoch Cree First Nation; visits with the Alexis Nakota Sioux and the Alexander First Nation in Alberta, plus the Simpcw and several other indigenous groups nearby in B.C. He has proselytized at conferences in major cities and in out-of-the-way coffee shops. The pace has been gruelling, with near-constant travel and workdays that often start before sunrise and extend into the early evening.

The conversations have informed the project's design, he says. For example, the company will drill under more roads and rivers than originally planned to lessen disruptions and the ecological impact of digging trenches. As a consequence of his travels, he can also tell you where to get the best meal in tiny Sooke, B.C., and jokes about his cache of coffee mugs stamped with chamber-of-commerce logos.

Because he often eschews prepared notes, Anderson's spiel in public forums tends to be more conversational, if meandering, than is typical of executive speeches. And he is not afraid to criticize politicians or his own industry. Such was the case when former federal Natural Resources minister and pipeline cheerleader Joe Oliver accused foreign radicals of hijacking regulatory reviews. Anderson publicly chastised him for needlessly sharpening opposition to major projects. At a Calgary speech last fall, he mused about the energy industry's inability to understand the forces aligned against it. It is a theme he returns to often—the need to stop finger-pointing and instead seek out solutions to vexing issues, be it climate change or aboriginal opposition to major infrastructure. "These are big issues for our society to wrestle with, and that requires conversation, debate and ultimately some accommodation," he says. "We've approached our project with that in mind: that we weren't going to be looking to others to solve our problems."

Michael LeBourdais, a former chief of the Whispering Pines/Clinton Indian Band in B.C.'s Interior, can attest to Anderson's willingness to find a compromise. He recalls butting heads with the executive in a Vancouver hotel during negotiations over the pipeline back in 2012. For LeBourdais, the sticking point was jurisdiction. Decades earlier, the band had been displaced from Clinton, B.C., owing to construction of a major hydro dam. LeBourdais's message to Anderson was blunt: "Don't come here and tell us what to do, or what you're going to do. It's my land." If their temperaments had been different, the enmity could have festered. Instead, LeBourdais and Anderson kicked the lawyers out of the room, leaving the two men to hash out an agreement. LeBourdais wanted the company to invest in the community's youth and its elders. "And, most importantly, keep the oil in the damn pipe," he recalls telling Anderson. "And he says, 'I want that too.' And that was the epiphany moment. We called our lawyers back in and said, 'We're not going to litigate any more. We're negotiating.'"

B.C. media mogul David Black, who has spent years as the chief promoter of a heavy-oil refinery on the province's northern coast, credits Anderson's dogged commitment to this type of engagement for getting the Trans Mountain project this far. "It isn't as simple as trying to get the permits and social acceptance to build a plant in a certain location," Black says. "You're building a plant that's 1,000 kilometres long, and you've got to get all those locations on your side."

Not everyone is swayed by Anderson's pitch. To some, he is merely "the friendly Canadian face on the giant American corporation," says Ben West of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation Sacred Trust Initiative, which opposes Trans Mountain on behalf of the aboriginal group whose traditional territory spans the province's southern coast. Stewart Phillip, head of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, adds that opposition to the project extends well beyond aboriginal communities and environmental groups. "These are rank-and-file British Columbians, retired people, grandparents, professionals who do not want to see the province suffer a catastrophic pipeline rupture or oil spill."

Phillip and his allies promise a protracted fight, arguing that public hearings on the project were flawed because they did not subject the company's claims to oral cross-examination. Already, several court challenges have been filed seeking to overturn approvals of the project, including one claiming conflict of interest due to Kinder Morgan and its oil-shipper customers being big donors to B.C.'s ruling Liberal Party. B.C. NDP Leader John Horgan remains staunchly against it, a position he will carry into the provincial election this spring.

In 2014, Kinder Morgan needed a court injunction to perform surveying work on Burnaby Mountain. The RCMP hauled away protesters in a scene that recalled the infamous "war in the woods" over clear-cut logging in Clayoquot Sound. The episode could be a prelude to more widespread demonstrations. The last time Kinder Morgan expanded its pipeline was in 2007, when it started threading 160 kilometres of new steel partly through Alberta's Jasper National Park. The work attracted scant attention from activists and aboriginal groups, but this was before pipelines became proxies for the battle against forces blamed for exacerbating climate change.

Northern Gateway's demise has now thrust Trans Mountain into the spotlight, notes Roger Harris, a consultant who for two years led aboriginal engagement on Gateway as an Enbridge vice-president. The Enbridge proposal was "the Darth Vader of energy projects," Harris says. "As long as Enbridge was out there, it was a bit of a distraction [from Trans Mountain], but once it was gone, these guys are the ticket. And they will draw all the attention and even more than what Enbridge drew." After all, the expanded Trans Mountain ends within walking distance of public transit connecting Vancouver to its suburbs, whose local governments have come out strongly against the project. "So it's kind of a worst-case scenario for them," says Harris.

Anderson concedes that security is a concern. Employees at the company's terminal operations in Kamloops who used to quiz him about pensions and salaries now ask how they should cope with civil disobedience. The company has been gathering intelligence on opponents for years. That includes keeping tabs on prominent protesters and their movements, and monitoring what's said on social media. Anderson receives weekly briefings, and the company is in close contact with the RCMP and local police in an effort to anticipate possible scenarios once shovels hit the ground.

Despite threats of blockades, Anderson insists construction will start in September. Oil could flow by late 2019. He deflects questions about specific threats, saying the project is merely entering a new chapter with new challenges. Trans Mountain is one of the largest capital projects Kinder Morgan has ever pursued, at a time when the company is grappling with weak oil prices and high debt. The company's share price slumped about 65% in 2015, though it regained some ground last year. Kinder Morgan is currently hunting for a joint venture partner to help cover Trans Mountain's hefty price tag. It is also considering selling shares of its Canadian business in a public float.

The stakes are high for more than just Anderson and Kinder Morgan. The pipeline has become a test of the Trudeau government's implicit bargain with the energy sector: that a more stringent environmental policy, including carbon pricing, will make major oil projects such as Trans Mountain more palatable to a skeptical public. Anderson knows he'll never get everyone on board, yet he remains convinced that all Canadians have a stake in the outcome. "It's going to take a nation to build this," he says, "not just a company."

Ian Anderson, the president of Kinder Morgan reflects on the challenges ahead to see completion of his proposed pipeline.

Ed Ou