The first time Andre De Grasse raced the 100-metre dash, he was in high school. He wore gym shorts. He had to borrow spikes. He didn't know how to get down in the blocks, so he took a standing start. He still finished in less than 11 seconds.

That moment connects directly to Sunday night. Faced up against the greatest sprinter – perhaps the greatest athlete – in history, Mr. De Grasse proved he is one day going to be the fastest man alive.

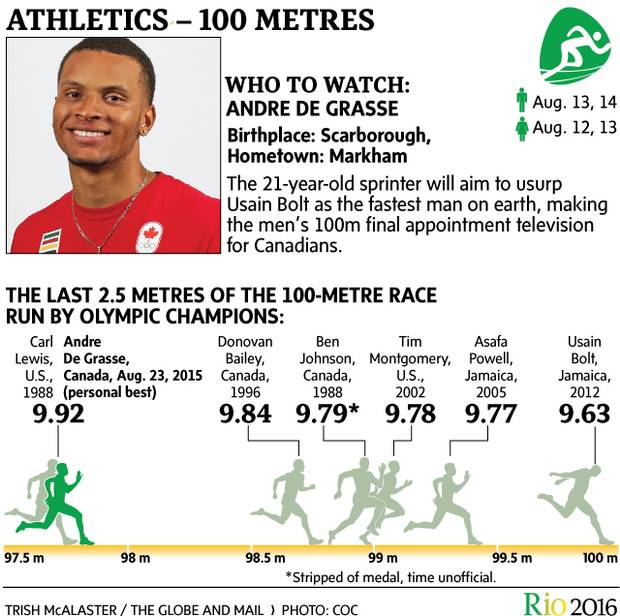

He finished only a tenth of a second behind winner Usain Bolt, good for a bronze medal. His 9.91-second finish was a personal best.

It seems that every time this 21-year-old takes the track, he is just a bit better. And his racing career has only just begun.

RELATED: De Grasse, Bolt and Gatlin: A brief oral history of the men's 100m race in their words

In the aftermath, Mr. De Grasse, who became the first Canadian male to win a medal at Rio, talked about a spot on the Olympic podium like it is a rest stop rather than any sort of destination.

"I have a lot to learn from that race," he said. "I know what I have to work harder for next year."

And, it goes without saying, three years after that. Tokyo 2020 will be Andre De Grasse's Games. Canada, you can mark it down.

Though few others in the world saw it that way, Mr. De Grasse had decided this race was a personal contest – the kid versus the king.

He goaded Mr. Bolt in the hours before the race.

After Saturday's preliminary heats, Mr. De Grasse said, "I've heard [Mr. Bolt's] not in the best of shape right now, so I feel like this is a good chance for me to take him down."

Later that same day: "I'm not going to wait until 2020. I want to do it now."

Sunday morning, on Twitter: "Looks like tonight is the night #NothingPersonal."

Whatever else he has yet to develop, De Grasse's confidence level is already charting historic highs.

With lines drawn, the storyline co-operated.

In the toughest of three semis, Mr. De Grasse and Mr. Bolt lined up beside each other.

Mr. De Grasse came out storming – a rarity for him. He had the measure of the rest of the field, looking once, twice, three times over his shoulder at the men behind him. But not Mr. Bolt.

As the defending champion hit the last ten metres, he deigned to look at the Canadian. He was grinning ear to ear. Here, finally, was someone who could do both talking and walking. Mr. Bolt seemed delighted. At the finish, he slapped hands with Mr. De Grasse. The pair finished 1-2 overall in the prelims.

In the final, they were once again shoulder to shoulder.

As he was introduced, Mr. Bolt winked and wiped dirt off his shoulder. When the cameras hit him, Mr. De Grasse mimed wrapping a championship belt around his waist. Runner v. runner and, perhaps more enjoyably, showman v. showman.

There are many great sporting events in the world. Each has their charms. None is as electric as this one.

The anticipation beforehand. The tension as the runners line up and practice surging from the blocks. The eerie silence when they take their stances. All you could hear at Rio's Olympic Stadium in that moment was the soft wash of rotor blades from a military chopper overhead.

In the first 40 metres, you knew Mr. Bolt had it. He rarely runs hard. He didn't seem to stretch himself on Sunday, either. He's been so far ahead of the chasing pack for so long, it will represent a small global tragedy when he begins to fade, as he must. He was always going to win this. No one knew that better than he did.

Justin Gatlin, the American who has been cast as a drug cheat and anti-hero here by his own teammates, was neither going to catch Mr. Bolt nor lose his place in second.

That left Mr. De Grasse and a few other chasers.

If Mr. Bolt and Mr. Gatlin are pure power, Mr. De Grasse is all will. He was behind in the first third. He made up space in the middle. He held off three other men – all far more experienced competitors – to take third.

Just as it's been for three Summer Games now, the 100 metres is really just an intro to the evening's entertainment. It's the fifteen minutes after that forms the bulk of The Usain Bolt Show. No great athlete since Muhammad Ali has had quite the same combination of talent and charisma.

At that moment, Mr. De Grasse had been mostly forgotten. As a medalist, he walked about draped in the Canadian flag. He grinned eagerly when Mr. Bolt came over to congratulate and stroke him.

What did he say?

"We were just joking around," Mr. De Grasse said. "He feels like I'm the next one and I'm just trying to live up to it."

It may not have been a passing of the torch – Mr. Bolt will turn 30 in a few days, but retains his total dominance over the sport. It only felt that way.

For Mr. De Grasse, one more small progression. He's only been a serious sprinter for a few years now. He's going to get bigger, refine his technique, improve his start. How many people can say they've got lots of room to improve, but are already the third-best in the world at something every single one of us does?

With the curtain coming down, Mr. De Grasse was freed to return to his usual self – a mild and easygoing fellow. The bragging had ended. He was looking forward, but no longer calling his shot: "I'm capable of doing it, the next Olympics."

Peter Eriksson, the head coach of Athletics Canada, was now acting as Mr. De Grasse's hype man: "I think he's on the stage where he can be one of the greatest Canadians ever. Sorry, [1996 gold medalist] Donovan [Bailey], but that's what I think he can be."

Canada's relationship to Olympic sprinting will always be a tricky one to navigate. That's Ben Johnson's legacy. Mr. Bailey was the first man to redeem it. Now that's Mr. De Grasse's job.

On Sunday night, a medal may have been the least of it. Coming out of Rio, he is now Mr. Bolt's heir and the man who will carry the bulk of our Olympic hopes for the next four years.

More from The Globe and Mail

Rio 2016 ‘This guy is magic’: Meet one of Andre De Grasse’s earliest track coaches

2:50