On Dec. 2 and 3, the personal collection of Neil Leifer – perhaps the greatest sports photographer ever – will be auctioned in New York. His work charts a vanished sporting landscape – where boxing and horse racing ruled, and where baseball was played in the afternoon. These aren't just pictures. They're time capsules. They show that while the games themselves don't change much, the way in which we see them does.

Bill Mazeroski

This may be the most famous hit in baseball history – Bill Mazeroski's Game 7, tie-breaking, bottom-of-the-ninth shot to win the 1960 World Series. The home-run ball landed outside Pittsburgh's Forbes Field, where a 14-year-old named Andy Jerpe picked it up. Police escorted Jerpe into the celebrating Pirates clubhouse. Mazeroski and a teammate signed it. A few months later, on the first nice day of spring, some of Jerpe's friends convinced him to use his holy relic in a sandlot game. Jerpe was hitting fly balls when he accidentally sliced one into a thicket of knee-high grass. A long search came up empty. The Mazeroski home-run ball was never seen again.

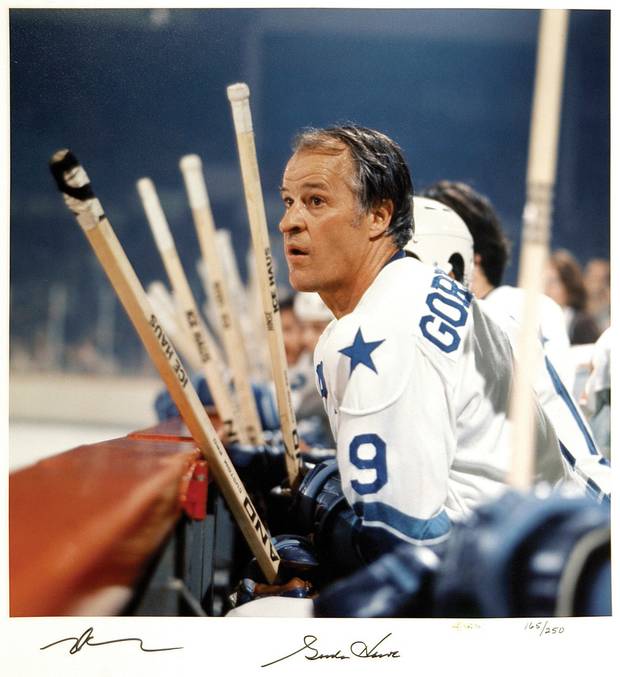

Gordie Howe

After finding retirement discommodious, Gordie Howe joined the World Hockey Association's Houston Aeros, aged 45. He was four years older than the coach. He played on a line with his sons, Mark and Marty. In one game, an opponent shoved 18-year-old Mark Howe onto the ice and pinned him there. When the elder Howe told him to let the kid up, the offender first chirped Howe and then yipped that maybe the kid should fight his own battles. "My dad reached over, put two fingers up the guy's nose and lifted him off Mark," Marty Howe recalled. "His nose stretched about a foot it seemed. I almost got sick watching it." It's uncertain if this photo captures Howe post-violence, or just contemplating the violence to come.

Secretariat

When we valorize racehorses, we talk in terms that might be used to describe a ballet dancer – "sleek," "lithe," "coltish." It speaks to elegance, which is not what crosses your mind when you get up close to one of these beasts. This photo gives you some sense of the reality – that a great thoroughbred is a battle cruiser fit to sail on land. Secretariat, pictured here, was so large in the chest – more than six feet around – that he required a custom-made girth. Here he is, piloted by Canadian jockey Ron Turcotte, winning the 1973 Kentucky Derby en route to a Triple Crown. Upon death, Secretariat's heart was found to weigh 22 pounds (10 kilograms) – more than twice the size of an average racehorse's. The veterinarian who performed his autopsy said, "I think it told us why he was able to do what he did."

Ali the conqueror

Muhammad Ali's prismatic personality functioned like a diamond. Depending on how he held himself in the light, he could show you something different, and often contradictory. There was never any harder man who allowed himself to seem so soft.

Of the hundreds of iconic photos of the 20th century's great sportsman, many are bright and airy. They show him in repose or at play. Ali's confidence was such that while he might be seen clowning, he knew he could never be mistaken for one.

This moment – the most epic and celebrated sports image of the century – is one of the very few in which Ali appears vicious.

He'd beaten Sonny Liston once, as Cassius Clay. A little over a year later, in May, 1965, he'd face him again here as Ali. The champion's political renaissance was so disquieting to middle America that during the fight, TV announcers continued to refer to him by his birth name.

It didn't last a round. Liston jabbed with his left. Ali came over it with a right. The punch was so quick, many claimed later they hadn't seen it, leading to charges of a fix. Liston dropped. After a few seconds, he tried to get up, wobbled, and collapsed again. That's when this picture was taken, with Ali looming over Liston, screaming, "Get up and fight, sucker!"

"[Ali] looked like a man in a different world," referee Jersey Joe Walcott would say afterward. "I didn't know what he might do. I thought he might stomp him or pick him up and belt him again."

You didn't see that on the broadcast, which aired in poorly framed black-and-white. During the knockdown, the camera tightened on Liston's face. Ali was unseen.

It wasn't until Leifer's photo was published that people got a real sense of Ali's imperiousness, and in glorious colour. It is the image of man as conqueror and conquered. It's victory at its most elemental, brutal and beautiful.

Pele in Mexico

After winning his first World Cup in 1958, a 17-year-old Pele fainted. Upon being roused, he burst into heaving sobs and was consoled by older teammates. Rarely has any top athlete ever seemed so young. Here he is in 1970 just after winning his third world title in Mexico's Azteca Stadium. He's not young any more. This is journey's end. In this moment, Pele has sealed his reputation as the greatest footballer of all time. He's a year from international retirement, but at his peak. Pele scored the opener in this contest, a header over Italian defender Tarcisio Burgnich. Afterward, Burgnich explained, "I told myself before the game, he's made of skin and bones just like everyone else. But I was wrong."

Ali from above

As bounded by the ropes, a typical boxing ring measures 20 feet square. Viewed from the side, it looks like a platform – permeable and unthreatening. But from above, the ropes are a hard boundary and the ring becomes a claustrophobic bear pit. That visual reimagining of a profoundly familiar space is what makes this 1966 shot iconic. We recognize the victor – Muhammad Ali. We've forgotten the man sprawled on the canvas – Cleveland Williams. Two years before this fight, Williams was shot by a policeman during a traffic stop and grievously injured. His return against Ali was just short of miraculous. Sadly, when Williams is remembered now, it is caged in this pose of defeat.

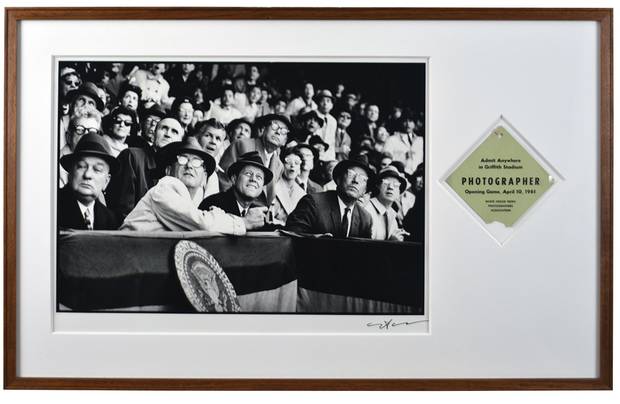

JFK's day at the ball game

Beyond the formal beauty of its composition, what makes this photo of John F. Kennedy taking in a baseball game notable is that the president is wearing a hat. Kennedy helped kill the ubiquitous fedora in the same way Clark Gable submarined the undershirt business – by being cool and refusing to wear one. Remember when presidents were cool? Accompanying the shot is Leifer's press credential. It has a small tear at the bottom. In a more trusting world, this was how the Secret Service indicated that Leifer was one of the photographers allowed close access to Kennedy. Perhaps the only thing that hasn't changed entirely since this shot was taken is what's happening off-camera – baseball. That's the same.

Koufax wins the World Series

They expanded the strike zone in 1963, tilting the board so far in favour of Sandy Koufax that it was functionally a fix. He's pictured here winning the World Series for the L.A. Dodgers in a sweep he manufactured nearly by himself. Koufax's gaudy numbers that season – a 1.88 ERA, 11 complete games, an insane 311 innings pitched – don't capture his dominance. After striking out 15 Yankees in Game 1 of that World Series, Yogi Berra said, "I can see how he won 25 games. What I don't understand is how he lost five." Koufax's teammate, Maury Wills, explained, "He didn't. We lost them for him."

Griffith vs. Paret

Cuban welterweight Benny Paret is dying in this photo. Though it will take him 10 days to succumb, he's just been beaten to death by 29 unanswered shots – many of them point-blank uppercuts – from American Emile Griffith. Griffith ended the fight in such frenzy that it took four men to drag him away from his unconscious opponent. Later, Griffith – a bisexual – would say his rage was spurred by an insult in Spanish from Paret – maricon ("faggot"). "He called me a name," Griffith said. "So I did what I had to do."

Fidel Castro

Though far from the best, here is the 20th century's most influential pitcher. According to legend, Fidel Castro was a baseball star at the University of Havana renowned for his heater. In different versions of this apocryphal story, a passel of big-league scouts contrived to let him slip their grasp, putting the Cuban Revolution in motion. Former major leaguer Don Hoak claimed he'd stood in against Castro, after the student revolutionary ran onto the field during a league game to make his point from the mound. In the end, Castro extended his career for decades playing a different sort of sport. "His fastball has long since died," a U.S. diplomat once said of Cuba's Maximum Leader. "He still has a few curveballs which he throws at us routinely."

Sugar Ray Robinson

This is a picture of the lion in whatever season follows winter, suddenly prey to the elements. Sugar Ray Robinson, Ring Magazine's "greatest boxer of all time," is 44 in this photograph. He's old and haggard. He's just lost another one. Looking back on it later, Robinson will observe, "You always say, 'I'll quit when I start to slide.' And then one morning you wake up and realize you done slid." Fortunately, Robinson's legacy was too great to be undone by an unwillingness to admit that time is the one life companion who will never lie to you.

Nadia Comaneci

Searching around for some gap in her armour, critics would say of teenage Romanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci that she took no pleasure in her work. "People always accused me of not smiling like my rival Olga Korbut, but that was just my personality," Comaneci wrote. Here she is displaying her five medals from Montreal 1976, looking as grim as a KGB commissar. In years since, the world has become inculcated with the American ideal of triumph – tears, joy, gaudy displays of emotion. Whether or not she enjoyed much of it, Comaneci remains in this image a powerful symbol of Cold War psy-ops – an imperturbable communist athlete. Also, an unbeatable one.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL