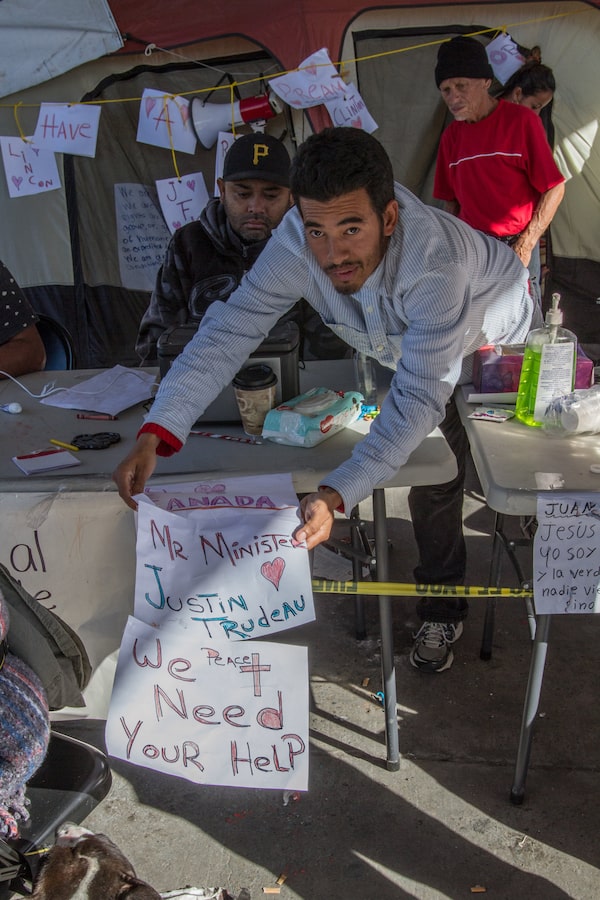

Honduran Jose Rodriguez, 30, who goes by Joseph, stands in a Tijuana migrant shelter on Dec. 9, with a sign he painted asking the Canadian government to help members of the Central American caravan.

The news spread quickly among the Central American migrants gathered at the U.S.-Mexico border in Tijuana: A Canadian archbishop had come to the city to say he would ask Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to create a special program to accept members of the migrant caravan.

At a November news conference, Leonardo Marin-Saavedra announced he was preparing a proposal for the Canadian government to airlift migrants to Canada, or charter a boat to take them to Vancouver or request that the United States allow busloads of migrants to travel north to the Canadian border.

A Canadian citizen who was born in Colombia and lives in Toronto, Mr. Marin-Saavedra is a writer and dramatist who is the archbishop of an independent religious organization called the Latin-American Anglican Church.

Canadian officials were aware of his proposal, he told migrants. But he warned that the plan was not guaranteed and the migrants would likely have to wait in Tijuana for several months, until the frigid Canadian winter had passed.

“We do not know if Canada says no, but I think Trudeau is going to say yes,” Mr. Marin-Saavedra told a gathering of hundreds of migrants.

Hours later, Alejandro Solalinde, a well-known Catholic priest and migrant-rights activist in Mexico, confirmed the plan, telling a migrant shelter in Mexico City that he was working with Mr. Marin-Saavedra to help arrange special Canadian visas for some of the migrants.

Honduran migrant Selvin Rodriguez Hernandez, 34, has been on a hunger strike in a makeshift encampment photographed on Dec. 9 2018, near the U.S.-Mexico border in Tijuana, Mexico, to draw attention to his wish to come to Canada.

As it turns out, the stories were little more than a hope and a prayer.

The Canadian government said it has also heard the rumours. It has been working with its embassy in Mexico and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to offer accurate information about Canada’s immigration system, but has no plans to resettle any of the migrants from the caravan.

“We are aware that misinformation is sometimes shared via social media, by private individuals and organizations that suggests the Canadian government gives asylum-seekers a free pass into Canada,” said Nancy Caron, spokeswoman for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. “These reports are entirely false.”

Canada, already dealing with an influx of asylum-seekers who have crossed the Canadian border from the United States, relies on refugee referrals from the United Nations Refugee Agency and other organizations, along with private sponsors.

None of the migrants, aid workers or NGOs who spoke with The Globe and Mail were aware of any outreach by the Canadian government. Instead, rumours of Canada’s generosity have spread like wildfire among many of the migrants who have arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border desperate to find safe haven in the United States. They have raised expectations that Canada should play a larger role in the Central American migrant crisis that has largely fallen on the shoulders of its North American neighbours.

Migrants in Tijuana say they have heard that Canadian government officials are circulating a list for people who want to go to Canada. Others have been told that Canada is desperate for workers to fill agricultural and construction vacancies, and has promised migrants jobs in the country. Some have been searching for the office that Canada is said to have opened in Tijuana to start processing asylum claims.

“From the moment we left Honduras, we knew that Donald Trump didn’t want us, but that Canada might be another option,” said Jose Rodriguez, 30, who goes by Joseph and travelled north in search of work to pay for his six-year-old daughter’s hernia operation. “So now Canada is the hope.”

To pass the time in a Tijuana migrant shelter, Mr. Rodriguez and a friend have started painting, often crafting artistic messages to Mr. Trump or to Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernandez. A day earlier, he unveiled his latest art project: a 10-foot banner featuring the Canadian flag and the words “Canada, I am still waiting for your response.”

Near the El Chaparral pedestrian border crossing from Tijuana into San Diego, Calif., a group of more than a dozen migrants have launched a hunger strike to draw attention to their plight, half of whom say they are trying to get Canada’s attention.

“I heard that Mr. Trudeau was seeking a program to give asylum,” said Selvin Rodriguez Hernandez, a 34-year-old Honduran who heard Mr. Marin-Saavedra’s speech on social media. He recently accompanied a German journalist to the Canadian consulate in Tijuana to plead his case, but said he was turned away.

Honduran migrant Selvin Rodriguez Hernandez recently accompanied a German journalist to the Canadian consulate in Tijuana, Mexico to plead his case, but said he was turned away.

“I want to go to Canada because there is more education there. There is more chance for young people.” Then he held up his sign: “We love Canada, Mr. Minister Justin Trudeau we need your help.”

Paola Gomez heard the stories, too, when she arrived in Veracruz, Mexico, to run an art project for children of the caravan last month. A lawyer from Colombia who came to Canada as a refugee and now works on immigration issues with the Toronto YMCA, Ms. Gomez was immediately alarmed.

“As soon as I heard this whole thing of people saying there are Canadian officials coming and getting everyone on an airplane, I thought: “Uh-uh. It doesn’t work like that,” she said. “I felt really obligated to start trying to explain this properly.”

So earlier this month, she travelled to Tijuana to visit migrant shelters and run Facebook Live events to explain how Canada’s immigration system actually works.

“My concern is that these families need to feel safe, and by having these expectations that aren’t realistic, it’s prolonging this idea of whether they’re going to go [to Canada]. I felt that someone needed to stay something.”

In an interview, Mr. Marin-Saavedra said he had no intention of spreading false hopes among the migrants with his proposal, which he still believes the Canadian government will adopt.

“They were not deluded,” he said. “They arrived in Mexico seeking to enter the United States. The Canada project is an alternative and we should all wait. In life, the only certainty is death.”

On Dec. 18, Mr. Marin-Saavedra mailed his proposal to Mr. Trudeau’s Papineau constituency office in Montreal. He says he plans to return to Tijuana in early January to update the migrants on Canada’s response.

If Canada says no, Mr. Marin-Saavedra says has other plans. He will bring his proposal to the governments of Australia, New Zealand and several European countries instead.

Tamsin McMahon

Tamsin McMahon