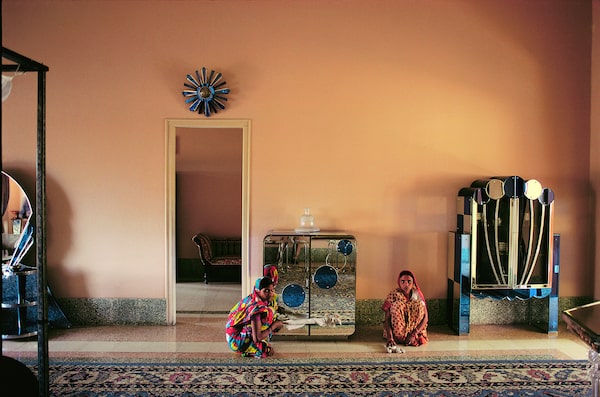

Employees, Morvi Palace, Copyright 2017, Raghubir Singh.

For three decades, the expatriate Indian photographer Raghubir Singh produced arresting images of his homeland. He shot the chaos of Calcutta, the bustle of Mumbai and the flow of the Ganges; in the streets and in the countryside, he created multilayered scenes of riotous colour, fractured perspectives and minute detail. He seemed to depict all India at work or at rest, yet repeatedly captured individual faces in the crowd: an exhausted porter, a crazed holiday reveller or a wary child suddenly pinpointed in the midst of a sprawling humanity.

Assembled together in Raghubir Singh: Modernism on the Ganges, an exhibition organized by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and now showing at the Royal Ontario Museum, these images from 1967 to 1997 make engrossing viewing and a powerful testament to a life’s work.

And yet, the shadow of #MeToo hangs over Modernism on the Ganges and accusations of sexual assault against Mr. Singh, who died of a heart attack at age 56 in 1999, can’t be hurried off to some historical lockbox alongside Pablo Picasso’s misogyny or Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian conquests. Now that those allegations have been aired – by a living American artist – Mr. Singh’s work inevitably demands a different approach. The #MeToo movement may not destroy his reputation nor this show, but it does call his methods into question and asks that a viewer look twice.

A Marwari wedding reception, Copyright 2017, Raghubir Singh.

When this exhibition appeared in New York last fall, Brooklyn artist Jaishri Abichandani told media that, in 1995, when she was a young woman trying to break into the art world, Mr. Singh offered her an unpaid job as his assistant on a professional trip to India during which he repeatedly demanded she have sex with him. Cut off from help in the days before cellphones, she was forced to comply. As the Singh show coincided with the #MeToo moment, Ms. Abichandani organized a protest performance outside the Met Breuer, the museum’s contemporary-art satellite.

The ROM was already contracted to bring the show to Toronto and the Canadian museum began debating how to deal with the issue. (Ms. Abichandani has never called on organizers to cancel the show, merely to acknowledge her, which apparently didn’t happen when the show visited Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts.)

The Toronto solution can be seen on the ground floor of the ROM just inside the main entrance: It’s a small, documentary display titled #MeToo and the Arts, which summarizes Ms. Abichandani’s story and protest, and offers video interviews with Canadian experts and ROM staffers as well as a timeline about #MeToo in the museum world. Canadian attention to sexual harassment in the arts has focused on the film industry, because that is where the scandal started, and on theatre and publishing, because that is where notorious cases have sprung up. The ROM’s timeline addresses the visual arts, particularly in the United States, where museums now face both allegations against living artists and complaints about the voyeuristic nature of much historical art.

Morning on Panchganga Ghat, Benares, Copyright 2017, Raghubir Singh.

Approaches are various – the National Gallery in Washington indefinitely postponed a show by artist Chuck Close; in Britain, the Manchester Art Gallery temporarily removed a 19th-century painting of naked nymphs – but only the Philadelphia Academy of Arts, with a small exhibit highlighting male power in art to coincide with a Close retrospective, seems to have struck on the same two-pronged approach as the ROM. Given the severity of Ms. Abichandani’s allegations, it’s an imperfect solution but an important one: The ROM’s #MeToo display has a significant footprint in an easily accessible space before visitors pay their admission and long before they reach Modernism on the Ganges.

That much larger show cannot fail to impress but for those who put two and two together, it does include images that may give the newly wary viewer pause. Take a 1982 photograph titled Employees, Morvi Palace, Gujarat; the term employees seems evasive rather than respectful: The two small women crouching on the ground are maids, clutching their cleaning rags. One of them is wiping down a mirrored cabinet and in that surface you can just make out a pair of trousered legs – the photographer’s own image. Mr. Singh would have known it was there: He played brilliantly with reflective surfaces in his mature work, including the remarkable Pavement Mirror Shop of 1991, a bristling mosaic of frames, glass and people that includes the photographer and his camera at the top of the picture. So, Employees is a picture of a man standing over two women.

Ganapati Immersion, Chowpatty, Copyright 2017, Raghubir Singh.

Similarly, images such as A Tribesman (1980), a man lying on a cart apparently too exhausted to close his eyes, or Slum Dweller (1990), a figure caged in his tenement, highlight the photographer’s mastery, both artistic and social: Mr. Singh was the child of an aristocratic family from Rajasthan. When Mr. Singh, from a distance, captures a plunging diver like a bird in flight, a nervous wedding party or a teeming crowd at a religious festival, he is distant enough that the viewer will mainly admire compositions that recall both a monumental European history painting and the multiple perspective points of Indian miniatures. But as he homes in on individual faces, you may wonder in what way he sought consent.

These issues of a street photographer’s power over often-unwitting subjects are hardly unique to Mr. Singh’s work, but this show, curated by Mia Fineman at the Met and organized for the ROM by curator Deepali Dewan long before Ms. Abichandani raised her hand, does not address them. Its lush and thoughtful catalogue talks about Mr. Singh’s influences – the black-and-white street photography of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the colourful compositions of Moghul court painting and the neorealism of Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray – and his remarkable innovations. Mr. Singh’s complex, fragmented compositions and his use of colour created a unique modernist idiom for India at a time when the West still believed art photography required black and white.

Vendor and Clients, Bundi, Copyright 2017, Raghubir Singh.

What Ms. Abichandani has done is demonstrate that we need a different Raghubir Singh show; indeed, a new approach to the work of many a photographer: The Columbia Journalism Review recently published an exposé of sexual harassment in that notoriously macho profession. Perhaps the most important contribution Toronto can make to Modernism on the Ganges will occur Oct. 9 when the museum holds a panel discussion on gender and power in photography. Mr. Singh is dead but the debate over his work is still evolving. Better than being forgotten.

Boy at bus stop, New Delhi, Copyright 2017, Raghubir Singh.

Modernism on the Ganges shows at the Royal Ontario Museum to Oct. 21.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor