Apple CEO Tim Cook wakes up at 3:45 every morning to stay on top of e-mails. Fiat Chrysler boss Sergio Marchionne rises at 3:30 a.m. to monitor European markets. There's a certain Type A mentality that suggests waking hours are also working hours. That sleep can be trained away – or at least economized – in pursuit of success. That success perhaps depends on it.

The attitude reaches many rungs below the boardroom. On a discussion forum dedicated to Fiverr, the online task marketplace for one-off $5-and-up freelance jobs, members talk polyphasic sleep schedules and micro naps in order to max-out the number of gigs they can complete in a day.

Taking up the milieu, a new exhibition by the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, titled Figures of Sleep, wonders: Is sleep in crisis?

According to a 2017 Statistics Canada report, one in three Canadians regularly gets less than the recommended seven hours shut-eye each night. There are a host of reasons why rest has become increasingly scarce: from deadline anxieties and 24/7 business practices that stretch work duties well past the eight-hour day the labour movement fought to regulate, to screen technologies that disrupt bodily rhythms.

Gabriel Orozco, Sleeping Leaves (Hojas durmiendo), 1990. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada.

Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

Figures of Sleep arrives as a new awareness around self-care has many better attuned to – and worried about – the maintenance of our physical and mental wellbeing. Curator Sarah Robayo Sheridan has gathered artworks by an all-star group of Canadian and international talents, including Liz Magor, Louise Bourgeois and Bruce Nauman, for a State of the Nation on sleep. Here, sleep is a matter of politics. It is a symbolic last bastion, Robayo Sheridan explains, positioned against the ever-accelerating demands of a capitalist market. Sleep can be a form of protest.

Inspired by Depression-era dance marathons, endurance contests where participants competed for cash prizes, a new video by Toronto-based artist Jon Sasaki explores exhaustion and failure. A dancer recreates poses from historical photographs of such events. Where one partner rested buttressed by the other, Sasaki's soloist must support himself. His muscles tremble and he tires quickly, trying then another ultimately intolerable position. The gloomy and vogueish workplace ethos comes to mind: Do more with less.

Jon Sasaki, A Rest, 2016. Choreographed solo performed by James Phillips, 9-10 minutes duration. Originally commissioned by the Toronto Dance Theatre.

Courtesy of the artist and Clint Roenisch Gallery

Across the hallway, visitors encounter a sleeping body arranged fetally beneath its blanket. Untitled (old woman in bed) by Australian sculptor Ron Mueck presents the gaunt, hyperreal figure in miniaturized scale, emphasizing the vulnerability of the sleeping body. (In Hesiod, Sleep and Death are twin brothers). Similar to the Chris Burden performance cited also in the exhibit, the sleeper is presented as a subject deserving of care and protection.

Chris Burden, Bed Piece, 1972. Market Street, Venice: February 18-March 10, 1972.

Courtesy of the Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

Ron Mueck, Old Woman in Bed (detail), 2002. Mixed media, 25.4 x 94 x 53.9 cm. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada. Copyright Ron Mueck.

Courtesy of Anthony d’Offay, London

But Rebecca Belmore questions which bodies are afforded that dignity with Dream Catcher, a tapestry created from the photograph – gotten with permission – of an Indigenous man sleeping on the sidewalk beneath a printed throw. We sew quilts and knit blankets for loved ones. Dream Catcher is likewise an act of care. It hangs in contrast to Rodney Graham's video rendition of the well-heeled sleeper, snug in what look like silk pyjamas, zonked on sleeping pills, and carried safely through the city by hired car. Our privileges afford us different types of rest.

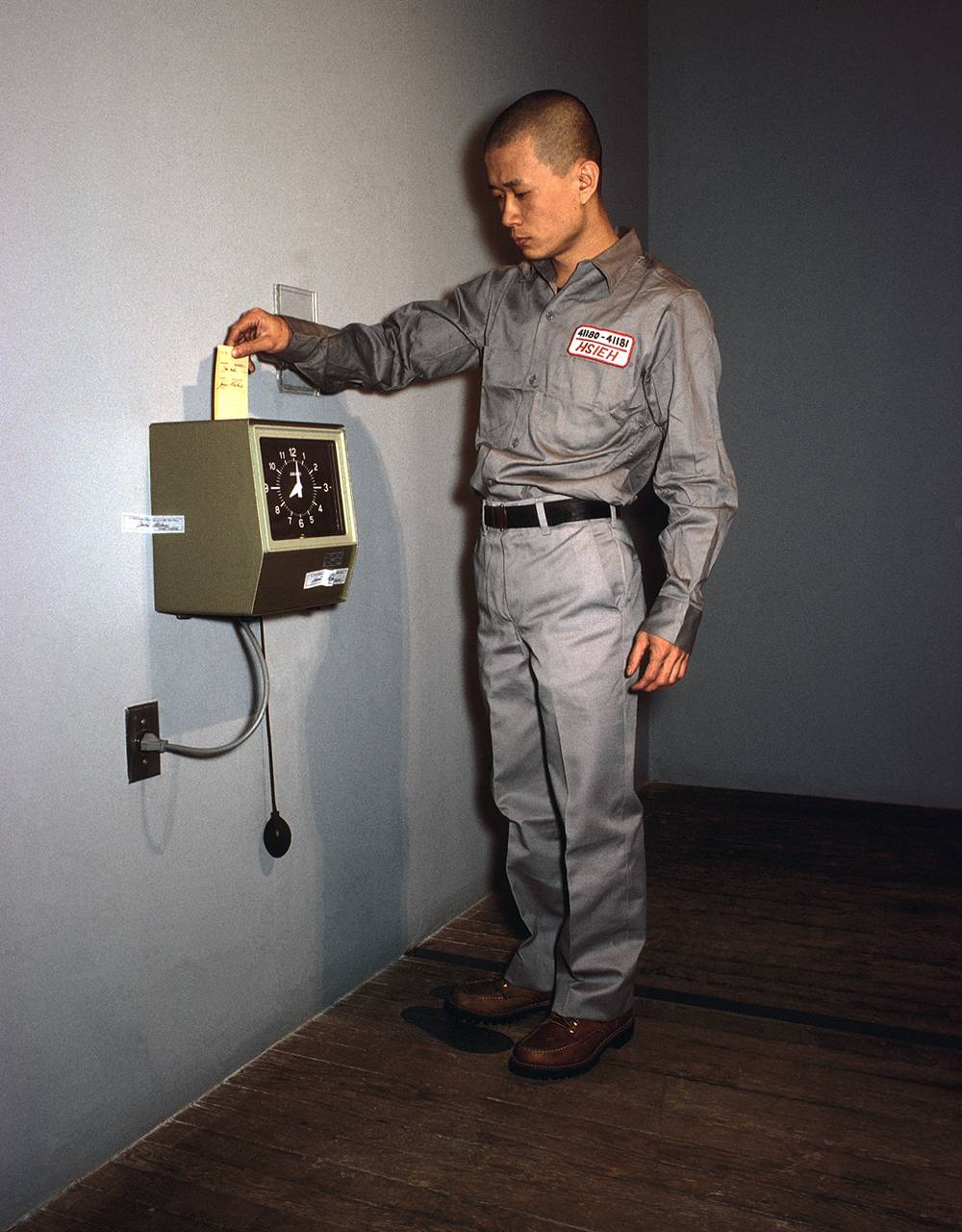

The artwork that feels most contemporary, however, is also one of the show's oldest. For one whole year, 1980 to 1981, Taiwanese-American artist Tehching Hsieh punched a time clock every hour on the hour. The clock would expose a single 16-mm-film frame with each punch-in, documenting the performance. The year's worth of photos, every single clock-on, is elapsed into a six-minute video. The hyperbolic vision of shift work appears prophetic now that we're never truly "off the clock" – as we sip our sixth daily coffee to fit in just one more Fiverr gig, as work stress permanently occupies some chamber of our mental engine, and as the e-mails roll steadily in right through the devil's hour and on to the morning alarm.

Figures of Sleep runs until March 3 at the University of Toronto Art Museum (artmuseum.utoronto.ca).