A school shaped like a doughnut, where children play by running laps around a roof deck. Does that make sense for people?

It does. Such a school – Fuji Kindergarten in suburban Tokyo, by Tezuka Architects – was awarded the Moriyama RAIC International Prize in Toronto on Tuesday. The global award, whose $100,000 purse makes it one of the richest prizes in architecture, goes to a single building anywhere in the world that transforms the society around it.

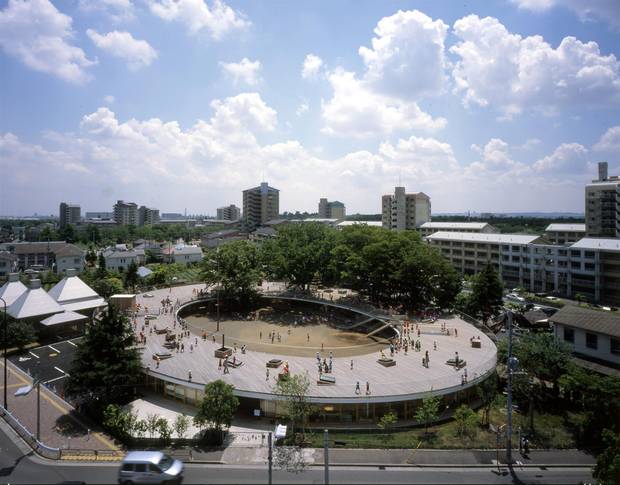

The kindergarten’s classrooms are organized around a circular courtyard, with sliding doors that are left open for most of the school year.

Katsuhisa Kida

Takaharu Tezuka, who runs the office together with his wife and partner Yui Tezuka, accepted the biennial award. Before the gala, wearing his daily uniform of a vibrant blue T-shirt, he explained that the prize's attention to the social impact of a building matches their aims. "It seemed that this prize was made exactly for us," Mr. Tezuka said, "but I did not expect to come so far."

Tezuka Architects beat out a short list of prominent Canadian, Danish and American architects. The other projects were Shobac Campus in Upper Kingsburg, N.S., by MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects; 8 House in Copenhagen by Bjarke Ingels Group; and the Melbourne School of Design at the University of Melbourne by John Wardle Architects and NADAAA.

The winning building, which serves a Montessori kindergarten, is distinctive. Its classrooms are organized around a circular courtyard, with few divisions between the class spaces, and sliding doors that are left open for most of the school year. "There is almost no division between spaces," Mr. Tezuka said, "and a minimum of division between inside and out."

The architects were responding to the school's request for a building that would encourage social interaction, independent learning and physical exploration. The rooftop deck, which is 183 metres in circumference, provides space for the children to run in a circle – and they do; a study by the architects found that pupils ran up to four kilometres in a day.

According to Mr. Tezuka, this concept came straight from the architects' own home. "At the time we had small kids, three and one – they kept running around the table in our house," he recalled. "And we thought, that is a way to make architecture. We made a circle, so children could keep running."

Trees grow up through the roof deck, surrounded by netting; the children can fall into these nets and then climb the trees, "learning how to fall a bit," Mr. Tezuka said, "which helps them be ready for life."

The world of architecture is full of such claims; contemporary designers are fond of elegant arguments, often backed by photographs that can be carefully edited and manipulated. The Harvard-educated Mr. Tezuka, who also worked for the prominent British firm of Richard Rogers, knows how to spin a tale. (He also understands how to maintain a brand; he wears the same hue of blue every time he appears in public, while his wife wears red.)

And yet to cut through the PR, the Moriyama Prize jury visited the building, along with the others on the short list, and conducted interviews with teachers, administrators and parents. This allowed the jury to verify some of the designers' qualitative claims, which include unusually equal social arrangements among the children and unusually high levels of academic focus – aided by the constant background hum of other children and ambient noise from outside.

The award jury described the kindergarten as ‘a giant playhouse filled with joy and energy.’

Katsuhisa Kida

"This is an extraordinarily positive place," the award jury said in a statement, "a giant playhouse filled with joy and energy."

The chair of the jury, B.C. architect Barry Johns, acknowledged that the kindergarten fulfilled the prize's ideal of building community and social equality. "All four projects really showed they were effective within their communities," he said. "The projects we were zooming in on were completely different, but each in their own way beneficial and powerful in their communities," he said.

Mr. Johns was also chair of the jury for the award's first incarnation two years ago. The prize, he argues, is advancing an agenda for contemporary architecture that goes beyond aesthetics for their own sake. "This is not a beauty contest," he said. "This is about architecture that really does transform people's lives."

Mr. Tezuka expressed a similar set of ideas. "I believe that architecture can change the world," he said. "I believe it can change the lives of people. But to do that, it is important to work with common sense. And for that reason, I like this prize a lot."